Building outward at last: sex, gender, and the toppling of Jewish Jenga

Part of a yearlong series about builders and building the Jewish future.

As a young girl in Orthodox Jewish elementary school, I vividly remember an educational poster in my classrooms. The poster displayed a Biblical Moses at the bottom, then Joshua (Moses’ successor) standing on his shoulders, then one leader atop another’s shoulders. It depicted the judges, the prophets and monarchs, Talmud’s rabbis, Medieval scholars like Maimonides and Rashi, up through history to the present era.

The poster’s message was clear. We learned that we stand on the shoulders of scholars and sages who preceded us. We could add our own voices, so long as we accept past beliefs and interpretations. We learned that anything else would be blasphemous, as if history’s gedolim (great ones) were Judaism’s foundation and, if we’re not careful, we might knock Judaism over.

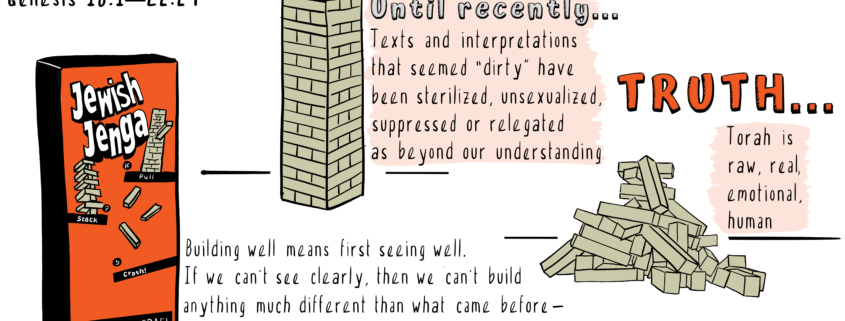

Today as a career Jewish educator, I’ve discovered that the vertical model of my elementary school poster is wrong. We needn’t only repeat and extend what came before – like we’re playing Jewish Jenga and any deviation left or right would cause Judaism to fall.

Today as a career Jewish educator, I’ve discovered that the vertical model of my elementary school poster is wrong. We needn’t only repeat and extend what came before – like we’re playing Jewish Jenga and any deviation left or right would cause Judaism to fall.

If modernity teaches any model for building the Jewish future, it’s a horizontal inclusive model, not a vertical one. A dynamically democratic approach to building the Jewish future, as Dr. Jonathan Krasner of Brandeis University describes about the history of Jewish education in North America, isn’t blasphemously not-Jewish. Rather, it’s especially Jewish.

This democratic model of building – to keep creating new Jewish ideas, designs and structures – is especially poignant amidst Judaism’s so-called “difficult texts.” Like magnets to charged metal, “difficult texts” attract interpretations and approaches charged with the socioeconomic and political contexts in which they arose. It’s not blasphemy to say so, any more than it’d be unscientific to call electromagnetism what it is.

So, let’s say so. Let’s talk about the contexts that embed “difficult texts.” Let’s talk about this week’s Torah portion (Vayera). Most of all, let’s talk about sex.

Let’s Talk about Sex

Vayera is a “difficult text” that magnetizes sexual and gender inequality. All in one paresha, we encounter the gendered value of personhood, women’s value as incubators, non-consensual sex, incest, domination and more. It’s telling if you’re uncomfortable reading these words, and it’s really telling if spiritual life hid from you parts of Vayera’s basic plot.

Here’s no-frills Vayera. Three strangers predict that Sarah, Abraham’s post-menopausal wife, will bear a son. Sarah laughs and calls herself “dried up.” Abraham next goes to the doomed “wicked” cities of Sodom and Gemorrah, to save his nephew Lot and family. As if to show how “wicked” these cities are, neighbors bang on Lot’s door demanding he let the locals get to “know” his guests by raping them. After the destruction, Lot’s daughters, believing their family to be the world’s only survivors, intoxicate their father to commit non-consensual incest and birth humanity’s next generation. Meanwhile, Abraham and Sarah travel to Gerar, where Abraham tells local leaders that Sarah is actually his sister, presumably so that when the local king wants to take Sarah for himself, the king won’t kill Abraham. Sarah’s voice is unheard.

But wait: there’s more. When Sarah bears the promised son of her own, it’s time to banish Hagar and Ishmael, the child whom Sarah forced Hagar to bear with Abraham. Abraham expels Hagar and Ishmael to the desert. Vayera ends with the famous “Binding of Isaac,” in which G!d tests Abraham by instructing him to slay the son Sarah awaited for so long, then sends an angel to stop Abraham at the last moment. We never hear G!d speak to Abraham again, and we never hear Sarah again at all.

Does some of Vayera’s plot seem unfamiliar? Did your rabbi, pastor, minister or teacher skip some parts, or present them in a sanitized way? Why?

“We are the other Victorians,” wrote Michel Foucault in The History of Sexuality in 1978. Only now might we be starting to emerge from sexual repression. Until recently – and still today in many circles – texts and interpretations that seemed “dirty” have been sterilized, unsexualized, suppressed or relegated as beyond our understanding. Nobody taught me earlier in life that Sarah couldn’t conceive because she was past menopause and her reproductive cycle naturally shifted. Nobody taught me that Sarah’s “dried up” self-concept was unhealthy. Nobody told me that Abraham and Sarah who conceived as seniors had a healthy sex life as seniors. Nobody taught me that the treatment of Hagar was abuse of Hagar. Nobody taught me that Vayera’s “dirty” depiction of homosexuality might be flat wrong by today’s lights.

Then again, in hindsight I’m not surprised because my Jewish education was mostly vertical, not horizontal. My elementary school poster taught me too well: men stood on the shoulders of men. Men defended text and sanitized text, and texts they couldn’t defend or sanitize they cast to the miraculous order. I could accept, or I could play Jewish Jenga and topple the blocks.

Why not read Vayera as it is – not to sanitize the text but to regard it as one of Torah’s most raw, real, emotional and human portions? Through this lens of reality, why not call the impulses that hid parts of Vayera in plain sight just what those impulses are – gendered and repressive?

Building well means first seeing well. If we can’t see clearly, then we can’t build anything much different than what came before – and thus equally gendered and repressive.

We can do better. We must do better

Dr. Christine Blasey Ford gave chillingly detailed testimony of her sexual assault. #MeToo shows that Dr. Ford’s experience is hardly unique. I am a survivor of sexual assault, as are many friends of all genders. When we suppress talking frankly about sex, we ill-serve our children. Only by talking about sex for real – not sterilized, sanitized or suppressed – can we teach what consent and power really are about. When we don’t talk for real, children can learn not to be real, that they should live (and expect others to live) into artificial gender ideals and roles. The result can be devastating (abuse, depression, suicide) – for them, for future partners and offspring, for neighborhoods, for learning communities, for Judaism and for all faiths.

So now is no time to stand narrowly on history’s shoulders. Now is a time to stand differently, so everyone can stand tall. Now is a time to build a Jewish future that doesn’t treat the enterprise of building like Jenga, as if it’d all topple if we don’t do just as was done before. Now is a time to teach spiritual building in ways that are horizontal, inclusive and unafraid to see and speak the whole truth – without need to sanitize, suppress or cast away.

And as we teach, model and build, let’s notice what we still feel we can’t safely say or see, what we still feel a need to cover over. Those impulses are clues to what still need a good repair. It’s what we won’t see and say that can most shake our foundations.

by Shoshanna Schechter; sketchnotes by Steve Silbert

Profound. This should be required reading both in the halls of our collective seminaries as well as in all day and congregational school staff development, particularly in those that wish to be trauma-informed communities.