Pinchas: Demanding rights, then and now (Numbers 25:10- 30:1)

Part of an ongoing series that explores Torah through an ethic of social justice and building a world worthy of the Divine

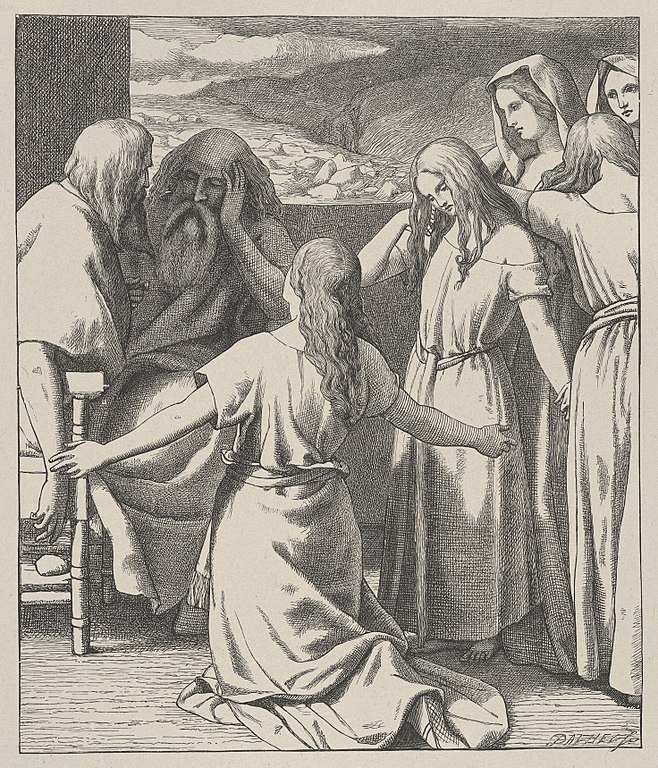

The Daughters of Zelophehad, print, after Frederick Richard Pickersgill, Dalziel Brothers (MET, 26.99.1(43))

Because I’m of a certain age, I remember watching my mother try to get her own credit card after she and my father were divorced. In fact, I’ll never forget it: I’ll never forget how humiliated I felt for her watching her try to get someone to understand that she paid the bills, and that the card which used to say “Mrs M” now needed to have her name on it. My mother wasn’t humiliated however, she was angry.

When I was first introduced to this Parshat Pincha, I was taught about the Daughters’ of Zelophehad, Mahlah, Noa, Hoglah, Milcah and Tirzah, five sisters who advocated for some ability to inherit land as inheritance and thus maintain the family name when their father died without any sons.

What is striking about them is that they were willing to stand, literally, before Moshe, Elazar, and the entire Israelite community and demand their inheritance (Numbers 27:2):

וַֽתַּעֲמֹ֜דְנָה לִפְנֵ֣י מֹשֶׁ֗ה וְלִפְנֵי֙ אֶלְעָזָ֣ר הַכֹּהֵ֔ן וְלִפְנֵ֥י הַנְּשִׂיאִ֖ם וְכָל־הָעֵדָ֑ה פֶּ֥תַח אֹֽהֶל־מוֹעֵ֖ד לֵאמֹֽר׃

There is a large portion of the classical commentary on this verse devoted to what “stand” means. The Gemara (BT Bava Batra 119b) suggests that the Daughters only received their inheritance because they were “wise [and] pious”, stating:

Is it possible that Zelophehad’s daughters stood before Moses and then Eleazar to ask their question, and they said nothing to them; and then the daughters stood before the princes and all the congregation to ask them? How would the princes or the congregation know an answer if Moses and Eleazar did not?

The Gemara answers:

Rather, transpose the verse and interpret it: First, the daughters went to the congregation and ultimately came to Moses, this is the statement of Rabbi Yoshiya. Abba Ḥanan says in the name of Rabbi Eliezer: Those enumerated in the verse were all sitting in the house of study, and Zelophehad’s daughters went and stood before all of them at once. They were not asked separately; rather, the order of the verse reflects their stature.

However, this is clearly, by simple reading of the verses, not true. What the Gemara suggests is that the Daughters’ were canny in their presentation of their request, but by re-reading the verses like this, the Talmudic rabbis are downplaying the audacity of what the women were demanding. And in any case, when the question is brought to God, God has no such problem responding:

“The plea of Zelophehad’s daughters is just: you should give them a hereditary holding among their father’s kinsmen; transfer their father’s share to them.”

And

“Further, speak to the Israelite people as follows: ‘If a man dies without leaving a son, you shall transfer his property to his daughter. […] This shall be the law of procedure for the Israelites, in accordance with the LORD’s command to Moses.”

In other words, by making their request, the Daughters’ of Zelophehad literally changed how the laws of inheritance are implemented.

Rabbi Silvina Chemen writes: “The achievement of Zelophehad’s daughters was a landmark in women’s rights regarding the inheritance of land, from those days up to now.” And she’s right about that.

While I was thinking about this drash, I decided to double check the laws around women and inheritance and ownership of land in the modern era. When were women allowed to own property? When were they permitted to control what they owned? The results of my search were disheartening to say the least.

One of the top results screamed out: According to the World Bank, Women in Half the World [Are] Still Denied Land, Property Rights Despite Laws (Press Release March 2019- Women in Half the World Still Denied Land, Property Rights Despite Laws (worldbank.org)). More than half the world’s population in half of the whole world!

And for those of us in North America who may want to rest on our laurels, until fairly recently, women who were entitled to property via their family (read father) lost title to that property upon marriage. It wasn’t until the nineteenth century that some property rights began to be available to women, slowly state by state in the United States. Even then, while they were entitled to ownership of land, they were NOT entitled to control of it. Control remained the province of their husbands, brothers, fathers, conservators of the courts. Beginning in the 1870s, married women in many states became entitled to control over their own earnings. It wasn’t until the 1970s (remember my mother?) that women were able to control their own earning and spending.

But there is still so much that needs to be fixed. There is still so much inequity that continues to exist, and even grow.

I can’t help but think about my friends, who lost partners in the early 1980s to AIDs, who also lost their property because ownership laws are still not guaranteed. As the Supreme Court starts eating away at the small rights women and LGBTQ+ people have managed to claim for themselves in the past few decades, what’s going to happen to our inheritance rights? Our rights to inherit our partners’ Social Security Benefits, for instance. Our rights to healthcare and health insurance.

If, as Rabbi Chemin also states: “the most important legacy of Zelophehad’s daughters is their call to us to take hold of life with our own hands, to move from the place that the others have given us–or that we have decided to keep because we feel immobile–and to walk, even to the most holy center”, then how we face the challenges of today’s world can in fact be informed by their decision to stand before the community, and demand their inheritance.

If the Daughters of Zelophehad were able to change a law that came down from Sinai, what might we be able to accomplish standing in front of our community today?

R. Cynthia (Cyn) Hoffman is a member of the Bayit Board of Directors.