Bedikat Chametz: Readying to Build Anew

Everyone in Jewish life is called to be a builder: that’s Bayit’s guiding principle. As Passover approaches, we’re called to take a long hard look at our tools and our stuff, discerning what needs to be discarded. Enter the ritual of bedikat chametz, searching for leaven.

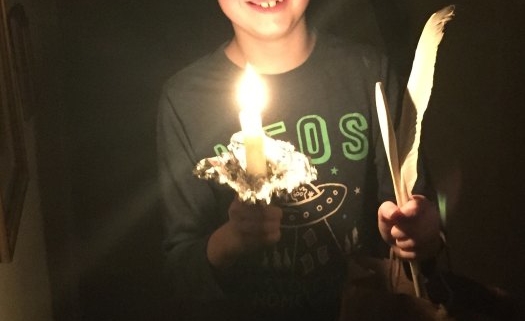

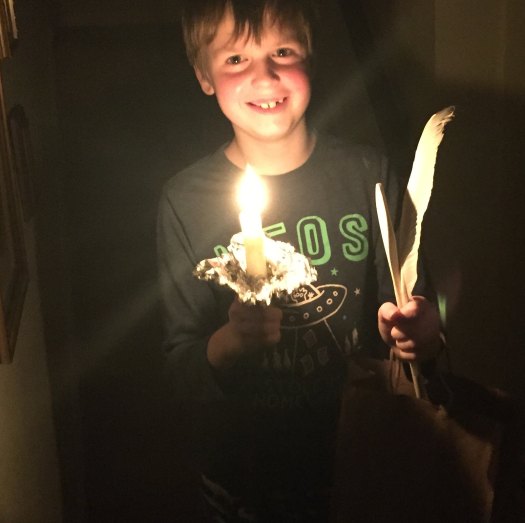

Bedikat chametz is a ritual of hiding pieces of leaven around the home on the eve of Passover, searching by candle-light, declaring any remaining chametz to be ownerless, and burning the chametz: an offering-up (both literal and symbolic) of home and hearth’s old crumbs.

In one understanding (drawn from Hasidic tradition) chametz can mean not only literal leaven but also the puffery of ego and the sourness of old ideas: the spiritual equivalent of the Tupperware left too long at the back of the fridge. For we who frame our Judaism around the core imperative of building, chametz could also mean old blueprints for projects that never got off the ground, or tools that don’t meet the spiritual needs of tomorrow, or the stories we tell ourselves about why we don’t have what it takes to build vibrant, authentic spiritual life.

The original matzah of the Exodus story is waybread baked in haste. It reminds us that the only way to reach liberation is to stop dilly-dallying, to grab what we can carry and start walking. How can we train ourselves to relive that urgency? How can we teach ourselves to leap into the unknown, certain that the Jewish future demands our risk-taking and our willingness to (in the words of Magic Schoolbus’ heroic Ms. Frizzle) “take chances, make mistakes, and get messy”?

Bedikat chametz is one of tradition’s tools for this task. Begin on the eve of the day that will become Pesach. Whether or not you’ve cleansed your home of the five “leavenable grains,” hide a few crackers or crusts of bread. Before beginning the search, recite the blessing:

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה, יהו׳׳ה אֱלֹהֵינוּ, מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם, אָשֶר קִדְשָנו בְמִצְותָו, וְצִוָנו עַל בִעור חָמֵץ.

Baruch atah, יהו׳׳ה Eloheinu, melech ha’olam, asher kid’shanu bemitzvotav, vetsivanu al bi’ur chametz.

Blessed are You, יהו׳׳ה our God, Source of all being: You make us holy in connecting-command, and enjoin us to remove chametz.

Pause for a few minutes of silence. (Maybe set a bell-timer on your phone, and give yourself some minutes of silence in the darkness.) Imagine your heart, your inner world, as a house with different rooms. Imagine yourself walking into each room of your heart, with a whisk broom and dustpan, and cleaning out the chametz you find there. Maybe you’ll find the chametz of old narratives that no longer serve. Maybe you’ll find the chametz of old plans that were never fulfilled, or broken relationships never wholly mourned. Maybe you’ll find the chametz of an antiquated God-concept that doesn’t connect you with the Source of Holiness any longer.

When you’re ready, open your eyes, light a candle, and go gather the chametz you purposefully hid. After the search is complete, say:

If there is any chametz I do not know about, that I have not seen or removed, I disown it. I declare it to be nothing—as ownerless as the dust of the earth.

The next morning, take it outside — I recommend doing this on your barbecue grill, if you have such a thing, though you’ll know best how to safely kindle a fire where you live — and burn it.

I have a longstanding custom of saving my lulav, the branches of palm and myrtle and willow from Sukkot, and using that as kindling to start my fire: an embodied connection between the old fall and the coming spring. Branches that were green and fragrant back in September or October have dried to a rattling husk now. Like the old ideas and plans and stories that once held life but didn’t get used to their full potential. Time to use them to catalyze something new.

As the branches and your chametz become ash, as smoke rises toward heaven, take a deep breath. Relax your shoulders. Let the old become ash, and resolve to let the ash fertilize the new growth of spring, the new building of your Judaism that is yet to be.

By Rabbi Rachel Barenblat.