Behar-Bechukotai: On humility, complacency, racial justice and equity, and the work that we cannot desist from

Part of an ongoing series that explores Torah through an ethic of social justice and building a world worthy of the Divine.

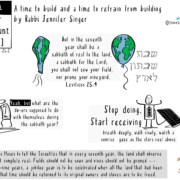

This week’s portion, Parashat Behar-Bechukotai, brings Vayikra, the book of Leviticus, to a close by detailing the rules of Shmita.

“Adonai spoke to Moses on Mount Sinai: When you come to the land that I am giving you, the land shall rest a Sabbath to the Lord…. But in the seventh year, the land shall have a complete rest a Sabbath to the Lord… it shall be a year of rest for the land. And [the produce of] the Sabbath of the land shall be yours to eat for you, for your male and female slaves, and for your hired worker and resident who live with you, and all of its produce may be eaten [also] by your domestic animals and by the beasts that are in your land” (Leviticus 25, 2-7).

In an unusual twist, the location of where this particular commandment is noted. Why is this? Is there a special connection between the shmita and Mount Sinai? The commandment regarding shmita is no different than all the others that were give to Moshe, so why is the location noted so prominently?

One midrash explains this by describing an argument between mountain. When Adonai wanted to give the Torah to Israel, Mount Carmel and Mount Tavor came forward. Tavor bragged that “It would be fitting for the Shechina to rest upon me, for I am higher than all the other mountains,” while Carmel insisted that it would be a better place, “because I was placed in the middle, and they crossed the sea over me.” Adonai instead proclaimed that they had already been disqualified and chose Mount Sinai, “which is lower than all of you.”

This midrash teaches us that Torah cannot be given in a haughty and “holier than thou” manner, but with humility. We also know that Moses was described as “exceedingly humble, more so than any person on the face of the Earth.” So, what is the lesson for us as social justice advocates?

photo source: Religious Action Center for Reform Judaism’s Racial Justice Campaign, learn more here: Racial Justice | Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism

As Jews, we are commanded to work towards tikkun olam, repairing the world. We do this daily by fighting for equal rights, climate change reform, fair abortion access, and a myriad of other things. We have accomplished many things in the social justice sphere, but it can be easy to trumpet our triumphs and overlook the gaps in our work.

An example of this is the fight for racial justice and equity. Jews were a part of the civil rights movement, a proud moment in our history that is evoked frequently. Many synagogues and Jewish organizations have taken up the mantle of fighting for racial justice, from voting reforms to protesting police brutality. We have also made great strides in embracing the rising number of Jews of Color and addressing racism within our institutions. Yet, when we look closer, are we really doing all we can?

Yes, we can point to the rising number of Jews of Color in our congregations, but are they in leadership? Are we uplifting the leaders and people of color who are heading up racial justice reform? Are we diversifying our programming and curriculums to reflect the true diversity of the Jewish diaspora? Are we truly advocating in a way that is making the world a better place or are we simply talking the talk and being as haughty as Mount Tavor and Mount Carmel?

As a people, Jews have done great things in the social justice sphere and it can be easy to think that our work is done when it comes to racial justice, but there is so much more to do. We must celebrate our victories, but we cannot become complacent. As Rabbi Tarfon tells us, we are not obligated to finish the work of repairing the world, but neither are we free to desist from it.