Parsha Vayeira – Ancestral Allyship and Intergenerational Impact

Part of an ongoing series that explores Torah through an ethic of social justice and building a world worthy of the Divine.

Part of an ongoing series that explores Torah through an ethic of social justice and building a world worthy of the Divine.

כִּ֣י יְדַעְתִּ֗יו לְמַ֩עַן֩ אֲשֶׁ֨ר יְצַוֶּ֜ה אֶת־בָּנָ֤יו וְאֶת־בֵּיתוֹ֙ אַחֲרָ֔יו וְשָֽׁמְרוּ֙ דֶּ֣רֶךְ יְהֹוָ֔ה לַעֲשׂ֥וֹת צְדָקָ֖ה וּמִשְׁפָּ֑ט לְמַ֗עַן הָבִ֤יא יְהֹוָה֙ עַל־אַבְרָהָ֔ם אֵ֥ת אֲשֶׁר־דִּבֶּ֖ר עָלָֽיו׃

For I have cherished him, because he commands his children and his household after him that they keep the way of Hashem, doing charity and justice, in order that Hashem might bring upon Abraham that which God had spoken of him.” )Genesis 18:19)

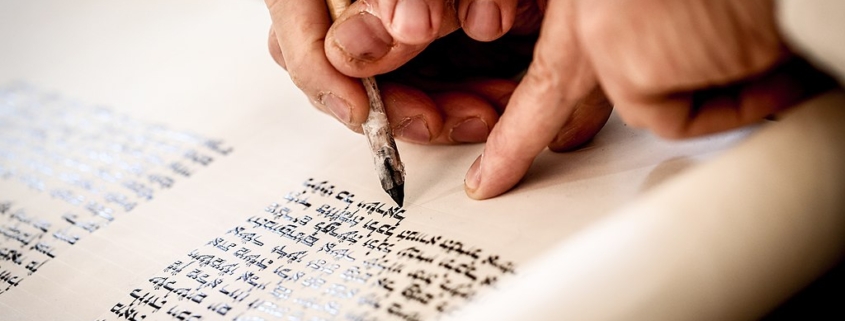

The very first Mitzvah in the Torah is the commandment to be fruitful and multiply. The last is to write a Sefer Torah. In the mystical tradition, the former can be fulfilled through the latter.[i] “זֶ֣ה “סֵ֔פֶר תּוֹלְדֹ֖ת אָדָ֑ם,[ii] understood homiletically as: “This book is the progeny of a person”. Practically, this extends to one’s חידושים – original ideas in Torah,[iii] as well as good deeds.[iv]

At this point in Abraham’s life he doesn’t yet have children, nor has the Torah been given, but still God testifies to Abraham’s intergenerational commitment to “the way of God”. The Zera Kodesh[v] explains that a person should never be satisfied with just serving God all the days of their life, but should instead desire to serve God all the days of the universe!

Descendants, whether biological, theological, or the natural consequences of our actions, perpetuate our contributions to perfecting the world. This is meant to be empowering, in that we shouldn’t limit the vision of a particular choice to its immediate impact, and also comforting to know that our efforts can continue beyond our time.[vi]

Resh Lakish asked his teaching assistant to say a few words in honor of those who comfort mourners:[vii]

“קוּם אֵימָא מִלְּתָא כְּנֶגֶד מְנַחֲמֵי אֲבֵלִים.

The assistant responds:

פָּתַח וְאָמַר: ״אַחֵינוּ גּוֹמְלֵי חֲסָדִים בְּנֵי גּוֹמְלֵי חֲסָדִים, הַמַּחְזִיקִים בִּבְרִיתוֹ שֶׁל אַבְרָהָם אָבִינו.

Our siblings, bestowers of loving-kindness, children of bestowers of loving-kindness, who embrace the covenant of Abraham our Patriarch.”

An aspect of this covenant is that we are both beneficiaries of the kindness that came before us – בְּנֵי גּוֹמְלֵי חֲסָדִים – and we are able to bequeath it to those who come after, as an extension of all of humanity. King Solomon wrote:[viii] …רֹ֭דֵף צְדָקָ֣ה וָחָ֑סֶד יִמְצָ֥א חַ֝יִּ֗ים צְדָקָ֥ה” – one who pursues righteousness and kindness will find life, righteousness…”. This is understood to mean that the righteous act itself, reproduces and creates additional life, in the form of continued righteousness.[ix]

Eulogies are intended to highlight the unique constellation of good character traits of the deceased, as a way of inspiring those listening to incorporate these qualities into their lives. This is an important pivot from the time of onninus before the funeral, when immediate family members do not engage in spiritual pursuits. It is a way of being sensitive to the shift from an embodied modality of impact, to one that relies on those actions already performed.[x]

The Ari Z”l, on the verse[xi] “צִ֭דְקָתוֹ עֹמֶ֣דֶת לָעַ֑ד – one’s righteousness stands forever”, observes that the word “צדקה”, in the numerical א”ת ב”ש ד”ק ה”ץ,[xii] is still “צדקה”, reflecting the transcendent nature of goodness. This is also alluded to in the charge of the Members of the Great Assembly: וְהַעֲמִידוּ תַלְמִידִים הַרְבֵּה – the literal translation is to raise up a lot of students, or perhaps to raise the students up a lot. A deeper intention of this direction is for the students to internalise that the Torah that they will bring into the world will stand indefinitely.

In the final song of the Torah,[xiii] Moses instructs us: “זְכֹר֙ יְמ֣וֹת עוֹלָ֔ם בִּ֖ינוּ שְׁנ֣וֹת דּוֹר־וָד֑וֹר שְׁאַ֤ל אָבִ֙יךָ֙ וְיַגֵּ֔דְךָ זְקֵנֶ֖יךָ וְיֹ֥אמְרוּ לָֽךְ׃ – Remember the days of old, understand the years of generation after generation”. Remembering is always a call to action and the memories of our ancestors provide an opportunity to be influential by continually informing our lives.

The Mattersdorfer Rav offers a beautiful reading of the Gemera in Kiddushin[xiv] about the way that we treat our parents. The Braisa teaches: “תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן אֵיזֶהוּ מוֹרָא וְאֵיזֶהוּ כִּיבּוּד מוֹרָא לֹא עוֹמֵד בִּמְקוֹמוֹ וְלֹא יוֹשֵׁב בִּמְקוֹמוֹ וְלֹא סוֹתֵר אֶת דְּבָרָיו – What is fear and what is honor? One may not stand in one’s parent’s place, and may not sit in their place, and may not contradict their statements.” He reframes this teaching “לֹא עוֹמֵד בִּמְקוֹמוֹ וְלֹא יוֹשֵׁב בִּמְקוֹמוֹ” to mean even when the parent is “no longer standing or sitting in their place”, because they have passed away, the child is still “not rejecting their words”.

A “chaver”,[xv] in the Talmud, is someone who is so connected to righteous living that we can rely on a presumption that they acted in the proper way. This is also extended to their family after they have passed away:[xvi] “חבר שמת אשתו ובניו ובני ביתו הרי הן בחזקתן – a cḥaver that died, his wife and children and members of his household remain in their status.”[xvii]

The word for “generation – דור” has the same numerical value as “chaver – חבר”. The choices we make connect[xviii] us to those who came before, and to those will come after. Attaching ourselves to righteousness helps guarantee that justice will continue on after us and that the good impact of our deeds will continue in perpetuity.

Rabbi Mike Moskowitz, a founding builder at Bayit and also a member of Bayit’s Board, serves as Scholar-in-Residence for Queer and Trans Jewish Studies at Congregation Beit Simchat Torah, a flagship LGBTQIA+ synagogue in New York City.

[i] See Ari Z’l Ohr HaYashar Amud HaTorah

[ii] Genesis 5:1

[iii] See Otzros L’Horos Nason page 227

[iv] Tanchuma 1; Bereishet Rabbah 30:6

[v] On Genesis 18:19

[vi] “Guarding The Way [of God] – וְשָֽׁמְרוּ֙ דֶּ֣רֶךְ has the same numerical value of “לקבר המת – to bury the dead”.

[vii] Ketubot 8b

[viii] Proverbs 21:21

[ix] See Ben Yehoyada Bava Basra 10b “הצדקה מולדת צדקה אחרת כמוה”.

[x] Perhaps this is why taking care of the needs of the deceased is called חסד של אמת – kindness of truth, because the truest kindness is the type that we cause when we are no longer alive.

[xi] Psalms 112:9

[xii] A basic “reflective” transformation pattern, wherein the first and last letters of the aleph-bet transform into one another, as do the second and second-to-last, and so on.

[xiii] Deuteronomy 32:7

[xiv] 31b

[xv] The rabbinic word for “ally”.

[xvi] Avodah Zarah 39a

[xvii] See Meshech Chochma

[xviii] See Sfas Emes 642.