Running With Grace / Graceful Masculinity: Vayeira

וַיֹּאמַר: אֲדֹנָי, אִם-נָא מָצָאתִי חֵן בְּעֵינֶיךָ–אַל-נָא תַעֲבֹר, מֵעַל עַבְדֶּךָ.

And he said, “my lord, if I have found grace in your eyes, please do not pass from before your servant.” (Genesis 18:3)

Vayeira begins as Avraham, recovering from his recent circumcision, is conversing with G-d in a prophetic state. Suddenly, Avraham lifts up his eyes and sees three angels, presenting as men, approaching. He runs to greet them and then says, “My Lord, if I have found grace in your eyes, please do not pass from before your servant.”

With whom is Avraham speaking? If he is speaking to the three men, why does he address them in the singular? Rashi offers two understandings of Avraham’s words. First Rashi suggests that Avraham is speaking to the three men, but he is addressing the most important of the three and that is why he says “my lord.” Then Rashi shares an intriguing, alternative approach. Avraham is actually speaking with G-d, asking G-d to wait while he goes to welcome the potential guests.

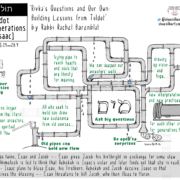

Based on this understanding of the verse, the Talmud teaches1 that “Welcoming guests is greater than receiving the Divine Presence”. But if Avraham is asking G-d not to pass on from him, why does he first run to the three men? Would it not make more sense to take his leave of G-d and then run to greet his guests? Also, how did Avraham know that it was acceptable to keep G-d waiting in order to service guests?

The Ramchal frames2 all of character development as an attempt to better understand G-d in order to act as G-d would act. “Walking in G-d’s ways – this includes all matters of uprightness and correction of character traits.” He explains that is what the Talmud3 means when it teaches “Just as God is full of grace and compassion, we should similarly be merciful and compassionate.4

The commentators5 observe that Talmud could have simply taught that we should be graceful and compassionate because G-d is, but instead the Talmud links our actions to G-d’s by making them conditional to be G-d like. In other words, the more we study and come to know G-d and the appropriate applications of G-d’s attributes, the more similar we can be to G-d.

Abraham started his quest to understand G-d very early on and now, 96 years later, he had perfected his body to be aligned with the Divine Will. R’ Nosson Gestetner writes that Avraham’s 248 limbs were so attuned to their corresponding 248 positive commandments that his body naturally was performing in G-dly ways.

As soon as his feet began to run towards the guests, he assumed that was what God wanted him to do. Because G-d is charitable, Avraham knew that he was also meant to be. Perhaps our verse should be understood as a question of approbation, after having left the prophetic state, asking “If I have found grace in Your eyes, if I have understood You correctly, this is what You want me to do – If I have properly found your way of gracefulness, please don’t leave me because I am not leaving you.” Avraham wasn’t just walking in G-d’s ways, but he was running!

Our relationship with G-d, however asymmetrical, is still reciprocal. Whatever Abraham did for his angelic guests himself, G-d performed directly for Abraham’s descendants. But whatever was done through a messenger, G-d also performed indirectly; mida k’neged mida, measure for measure. This principal can also be understood, homiletically, as reflecting G-d’s Midos, character traits. The more we understand G-d the more we can be like G-d, and then the more G-d shares G-d’s self in relationship with us.

Perhaps the mitzvah of welcoming strangers is the example given because one of the ways that we come to better understand G-d is by seeing different aspects of G-d in other people. It is now also a way to express to G-d, like Abraham did, that we come closer to G-d by treating people with kindness.

1. Bavli Shavuot 35b↩

2. Introduction to Path of the Just↩

3. Talmud Bavli Shabbat 133b↩

4.Rashi explains this teaching about grace, from Abba Shaul on the verse in Exodus of זה א-לי ואנוהו, through the etymology ואנוהו = אני והוא, me and G-d – that we should make ourselves like G-d by doing as God does, adding to the Braisa’s understanding of אנוהו as the act of beautifying a mitzvah↩

5. בלבבי משכן אבנה↩

By Rabbi Mike Moskowitz