The Holiness In What We Must Remember To Forget: Shabbat Zakhor And Vayikra

Inscribed above the exit of Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust museum, is a quote attributed to the Ba’al Shem Tov: “Forgetfulness leads to exile, while remembrance is the secret of redemption.”

The wall above the eternal flame in the Hall of Remembrance of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC also invokes memory. “Only guard yourself and guard your soul carefully, lest you forget the things your eyes saw and lest these things depart your heart all the days of your life. And you shall make them known to your children and to your children’s children” (רַ֡ק הִשָּׁ֣מֶר לְךָ֩ וּשְׁמֹ֨ר נַפְשְׁךָ֜ מְאֹ֗ד פֶּן־תִּשְׁכַּ֨ח אֶת־הַדְּבָרִ֜ים אֲשֶׁר־רָא֣וּ עֵינֶ֗יךָ וּפֶן־יָס֙וּרוּ֙ מִלְּבָ֣בְךָ֔ כֹּ֖ל יְמֵ֣י חַיֶּ֑יךָ וְהוֹדַעְתָּ֥ם לְבָנֶ֖יךָ וְלִבְנֵ֥י בָנֶֽיךָ׃ Deuteronomy 4:9) .

Memory plays such a fundamental role in society. We are reminded to “never forget” the Shoah, along the lines of the maxim that those who forget the past are condemned to repeat it.

When we think of loved ones who have passed away, we say “zichronam livracha”, may their memories forever be for a blessing.

This week, this Shabbat, has a special name. It is called Shabbat Zakhor, the Shabbat of Remembrance (the Shabbat preceding Purim, one of four special shabbatot that come in the lead up to Passover, the holiday of redemption).

Memory, the past, we are taught, is essential to our future. “The secret of redemption.” Because it is only by engaging with the past, learning about how and why we came to be who and where we are, now, today, can we build and create a better tomorrow.

In many ways, that is the central element or function of my deployment as a rabbi – to be a trustee of our rich and varied history and a builder of a compassionate and compelling present and future.

For Shabbat Zakhor it is a mitzvah to read a particular passage of Torah – Deuteronomy 25: 17-19:

זָכ֕וֹר אֵ֛ת אֲשֶׁר־עָשָׂ֥ה לְךָ֖ עֲמָלֵ֑ק בַּדֶּ֖רֶךְ בְּצֵאתְכֶ֥ם מִמִּצְרָֽיִם׃

Remember what Amalek did to you on your journey after you left Mitzrayim. How he surprised you on the march, and cut down all the weak ones who were behind. When you were famished and weary and were not God fearing. Therefore, when Adonai your God grants you safety from all your enemies around you; in the land that your God is giving you as a hereditary portion. You shall blot out the memory of Amalek from under the Heavens. Do not forget! (Deuteronomy 25:17-19)

Tradition teaches us that Haman is descended from Amalek, and that before we celebrate Purim, we must remember that God will not be at ease until Amalek – represented as a symbol of cruelty to the weak, or the different, or the marginalized – is blotted out.

A teaching from the Hasidic source Iturei Torah (on parsha Zakhor) highlights what happens when we fail to care for each other, in interpreting why we must both blot out and remember Amalek:

Had the children of Israel not forgotten about the slower ones in back but instead, brought them closer under the protecting wings of God’s Presence, binding the slower to all of Israel, the Amalekites would not have succeeded in their attack. But because you allowed the slower ones to be aharekha (meaning both “behind you” and “other”), that you separated them off from you and made them “other”, and you forgot about your brothers and sisters, Amalek could viciously attack them. Therefore, the Torah tells us to remember Amalek, so that we never forget to bring our brothers and sisters who need special attention into our midst.

It can be hard to care for each other as communities made up of diverse individuals with different backgrounds, perspectives, and needs. But that is the challenge that Torah is giving us- to remember not to “other” each other, and in that way to blot out Amalek, the othering. In this piece of Torah we are commanded to work for the end of oppression to all those who may be left behind. Today that work is ever more important.

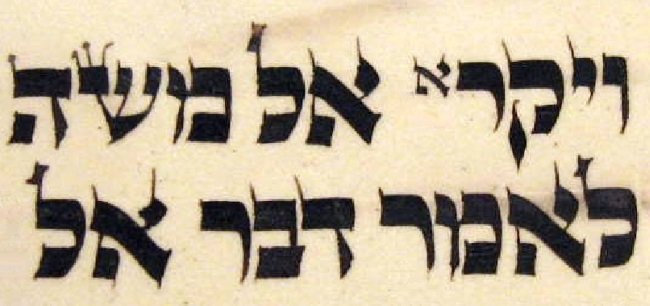

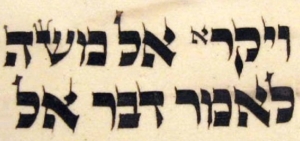

This Shabbat we also begin a new book of Torah, Vayikra (Leviticus), which details all sorts of rules of holiness and is also known as the Priestly Code. The name Vayikra is for the first word of the book, which begins “Vayikra el Moshe laimor”, “and God called to Moses saying…” As commentary throughout the ages has noted, there is something particular about the way the word vayikra is written in Torah scrolls: the final letter, the aleph, is noticeably smaller, almost like a footnote to the rest of the word:

The mediaeval rabbinic commentator Ba’al HaTurim suggested that the aleph of vayikra is small because Moses initially wanted to write vayikar (he happened), as it is said of Bilaam, as if God had only happened upon him accidentally. However, God told Moses to write an aleph, so he wrote it small. Some commentators have suggested this as a sign of Moses’ humility, and others a sign of God’s love for Moses.

Yet the aleph “א” is a special letter, first letter of the Hebrew alphabet, open in all directions, a symbol in many ways of divinity, of God, itself. On its own it has no sound, but embodies breath and life. When I look at the small Aleph at the end of vayikra “ויקרא,” I think of those left behind in the passage that we read from Deuteronomy. As the Iturei Torah wrote “The Torah tells us to remember Amalek, so that we never forget to bring our brothers and sisters who need special attention into our midst.” The small aleph at the end of the word vayikra, paired with this passage for Shabbat Zakhor, emphasizes how caring for the small and most vulnerable among us is not just right, but holy. The Divine resides in the aleph at the back.

As the Russian invasion of Ukraine enters its third week, and already 2.5 million Ukrainians have fled the country as refugees, we remember that many of us also once fled that region as refugees. And we must act. As we mark two years since COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic, we remember those whose lives were lost or irreparably changed by the virus, and those who have struggled to keep afloat amidst all the disruption since. As pandemic mitigation measures are lifted, we remember those of us who are still more vulnerable, or too young to be vaccinated, or tired from nonstop care of others, and we must ensure we keep caring for and protecting each other, and not leave particularly the most marginalized amongst us, behind. As some countries move towards removing systemic barriers to equality in terms of racial justice, Indigenous reconciliation, accessibility, LGBTQ2+ rights, and more, we note that other countries and states are becoming ever more repressive, and we remember that it is on us, aleinu, to work towards justice.

May the wholeness and peace and promise and holy energy of Shabbat empower and invigorate us to continue to care for each other and work towards justice.