Why This Firstborn Will Go Silent Before Passover: The Social Justice Ta’anit Dibbur

Among Passover’s many customs, the fast of the firstborn (ta’anit bechorot) fell into disuse. This ritual fast, commemorating Egypt’s victims of the Tenth Plague’s death of the firstborn, finds little traction among modern liberal Jews. Even most traditionalists arrange a ritual joyous reason to avoid the pre-Passover fast.

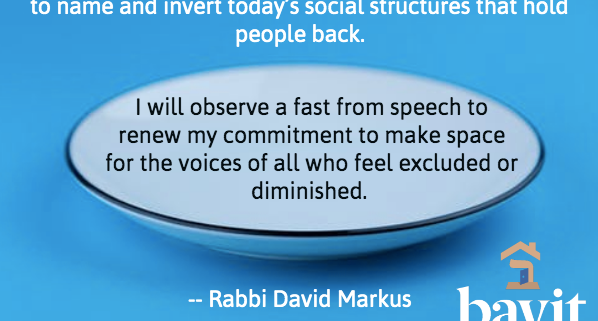

The day before Passover, however, this particular firstborn of Israel will fast – not just from food but also from speech. I will go silent – I will observe a total fast from speech (ta’anit dibbur) – and I will decline any excuse that might absolve me.

The reason isn’t virtue signaling. Rather, it’s to remind myself, and invite others to consider, that words and privilege can be as enslaving as iron shackles. It’s to renew my commitment to make space for the voices of all who feel excluded or diminished, whose identities or experiences have denied them privileges I enjoy – including the very privilege to write these words.

A Pre-Passover Fast from Food (Ta’anit Bechorot)

There are many reasons to fast before Passover – and not just make room for matzah! One reason is to mourn the too-high price of freedom. Talmud famously teaches that when angels rejoiced during the Exodus drowning of Egyptian soldiers in the Sea of Reeds, God rebuked them saying, “My children are drowning and you sing Me praises?” (Megillah 10b, Pesachim 64b). If Egypt’s first-born and soldiers died for Israelite liberation, their deaths are not less tragic. If angels had to learn that lesson, then so might we. Just as we spill drops of wine for each plague during the Seder (we can’t drink a full cup of joy at another’s expense), we can fast in poignant memory of the tragically high cost of freedom.

Another reason is to connect with today’s captives of body, heart or spirit. Until all are free, all are unfree. So taught Dr. Martin Luther King from his Birmingham jail cell: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” We can fast, as I wrote elsewhere, to spiritually purge for every time co-religionists ever sung praises for another’s degradation. We can fast to rededicate ourselves to bringing Passover’s global message of freedom to the whole globe.

A third reason is to honor this year’s calendrical confluence with Good Friday. Jews need not understand the Jesus of faith as Christians might, but we can understand suffering, grace and redemption in common cause with our Christian cousins as they commemorate their own ritual descent and ascent rooted in Passover.

A Pre-Passover Fast From Speech (Ta’anit Dibbur)

The idea of a ta’anit dibbur (fast from speech) traces from the wisdom of Proverbs 18:21: “Life and death are in the hand of the tongue.” We fast from speech as a practice of purification. By ritually controlling the incessant drive to speak, we can refine the inner impulses they voice.

All the more so before Passover. Mystics re-read Passover (pesach) as the speaking mouth (peh sach), the spiritual liberation that could heal both Moses’ impaired speech and our own. Understood this way, the creative impulse that Jewish mysticism understood as speech – God’s speech, and our speech – can be healed and channeled to liberate the sacred in our world.

Consider the countless injustices and shacklings expressed as speech. Consider the enormous power of words to include or exclude, create or destroy, empower or enfeeble, uplift or suppress, liberate or enslave. Words can wound, or words can heal. Understood this way, any Passover worth its weight in matzah must focus intently on the power of words to help purify our words.

What does this have to do with the firstborn? In its day, primogeniture stood for privilege and societal power dynamics that locked privilege into the day’s reality map. By dint of gender and birth order, the firstborn male held special status legally, politically and ritually. Others were at best second best. And as for the individual, so too the collective: God told Moses to call Israel “God’s firstborn” before Pharaoh (Exodus 4:22). Later, liturgy attributed to Rav Kook, Israel’s first chief rabbi, transformed Israel into reishit tzmichat ge’ulateinu, “the first flowering of our collective redemption.”

We’ve come far since primogeniture’s days, but Passover becomes a mere tasty relic if we rest on past laurels. A living Passover means bringing freedom and equality to all in the flowering of collective redemption. A living Passover means pushing boundaries outward until they include everyone, and feeling deeply wherever boundaries or the call to expand them feels tight. Those tight spots are our meitzarim, our “narrow places” – literally our “Egypt,” the frontiers of today’s Passover ongoing call to liberation.

Understood this way, the “fast of the firstborn” is a radical and evolving call to name and invert today’s social structures that hold people back. The “fast of the firstborn” isn’t mainly about the “firstborn” but rather about the privilege that primogeniture wrongly symbolizes. It’s strikingly beautiful that Judaism can honor Passover – a defining experience of peoplehood and liberation – with this internal hedge against its own imperfect realization of this sacred calling.

Now let’s get personal. I seem like the personification of privilege. I’m the firstborn child – and a son at that. I’m straight and cis-gendered. I hold two graduate degrees, from Harvard, plus a rabbinic ordination. I’m honored with a judicial role and a pulpit. I teach in seminary and I’ve led spiritual nonprofits. I have seemingly unfettered opportunities to speak, write and teach. I’m not just a man; euphemistically I’m The Man! And most who know me know that I can have much to say.

That’s exactly why I and people like me should go silent before Passover – to remind ourselves of the marginalization and subjugation that others experience daily, to make space for them, and to recommit ourselves to that cause as a way of life for all time.

To be sure, I wasn’t born on third base thinking that I’d hit a triple. I’m the son of an immigrant. I did not grow up affluent. I’m the first in my family to graduate from college. I faced and overcame many obstacles both personal and familial along the way. But such is the American experience and, often, the Jewish experience. All the more reason for me to make space for tomorrow’s “me” – whoever and however they may come.

I think of my own mom and countless other moms denied a Jewish education or countless other opportunities on the basis of sex. I think of LGBTQI friends still fighting whether in or out of the closet, denied their rights at tragic costs to themselves and society. I think of people of color, of all backgrounds, whose lives as visible minorities still are fraught 50 years after Dr. King was assassinated. I think of talented people of all ages and stages blocked from leadership by crusty, recalcitrant power dynamics that cling to their own false solidity. I think of Jewish life’s virulent allergy to wise succession planning that shortsightedly robs institutions of healthy and vibrant futures. And I think of many leaders who undoubtedly think they’re doing leadership right but who wield emotional or spiritual authority in ways that are pervasively self-perpetuating.

That’s why I will go silent before this Passover. I will reclaim the ta’anit dibbur as a deliberate space-making practice both within and without. I hope all firstborns, whether literally first out of the womb or metaphorical firsts of privilege, will consider doing likewise. Let’s make space for others starting with one day, then one week, then for a lifetime, for all Jewish life and for all life. Let’s make space to heal speech, to heal power, to heal the world.

When we break our ta’anit dibbur at the start of the Seder, let our first word be Baruch: ”Blessed.” Let that flow of blessing be the purpose of our speech and all speech. And in that merit, may we, all of us, experience a truly liberating and sweet Pesach.

By Rabbi David Markus