Building a Temple from Tears

Part of a yearlong series on Torah wisdom about building and builders.

The Torah is filled with instructions for building the Mishkan, G-d’s “dwelling place” that our ancestors carried in the wilderness, but those blueprints don’t provide measurements of the emotional dimensions needed to build that holy space within our hearts. It often feels like the walls we have constructed, to protect that space, are more permanent than the walls of the original Mishkan, designed to create an inviting space.

There are few things that penetrate our hearts more powerfully than the wailing cries of a child. We hear and witness the holy purity and unfiltered truth of their experience in real time. It is this portal into the honest rawness and exposed feelings of human vulnerability that naturally move us to open up our own emotional channels.

Tears can be powerful, cleansing, and soulful. They can also be the result of overwhelming pain. Regardless of the part of us that hurts, it is the eyes that cry. No other part of our body is as sensitive to the basic material of the physical world. Even one speck of dirt in the eye can be excruciating and incapacitating, where it would go completely unnoticed nearly everywhere else on the body.

Tears can be powerful, cleansing, and soulful. They can also be the result of overwhelming pain. Regardless of the part of us that hurts, it is the eyes that cry. No other part of our body is as sensitive to the basic material of the physical world. Even one speck of dirt in the eye can be excruciating and incapacitating, where it would go completely unnoticed nearly everywhere else on the body.

Our Rabbis teach that we come into this world crying because the soul feels the pain of just being forced into this physical and constrained space of a body. Crying, it seems, is also a bridge back to that spiritual habitat. The Talmud teaches that although the gates of prayer are sometimes shut, the gates of tears are never closed. If so, asks the Kotzker Rebbe, why then do they need gates at all? He answers that only true, heartfelt tears are let in. It is not coincidental that the Hebrew word for crying (בכי) has the same numerical value as the word for heart (לב).

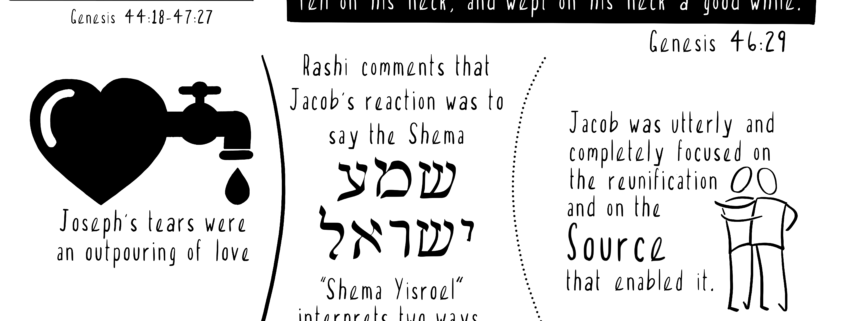

So why in this week’s Torah portion didn’t Jacob cry with his son Joseph, when they are finally reunited? The verse (Genesis 46:29) observes that “Joseph harnessed his chariot and went to Goshen to meet his father Israel, and he appeared to him, fell on his neck, and he wept on his neck excessively.” Rashi comments that while Joseph wept greatly, continuously, and more than usual – Jacob however, did not fall upon Joseph’s neck nor did he kiss him but instead said the Shema.

When we recite the Shema, we close our eyes and give testimony to our faith and total commitment to the One that we can’t see, but know to be the source of it all.

שמע ישראל ה׳ אלהינו ה׳ אחד

The large “ע” and “ד” spell the words for “witness” and “knowledge”. Saying the Shema is  a demonstration of our inner truth and willingness to serve G-d “With all of our heart, with all of our soul, and with all of our might”.

a demonstration of our inner truth and willingness to serve G-d “With all of our heart, with all of our soul, and with all of our might”.

The six letters of the first and last words are an acronym for six people who sacrificed their lives in the service of G-d, and were miraculously saved . These two words are 1 also acronyms for the six different literal sacrifices that were offered in the Temple , 2 often compared to the neck, where we are told heaven and earth are connected.

Perhaps Jacob’s absence of tears wasn’t a denial of a shared experience, with his son, but rather an expression of it.

The verse can be read as “Shema Yisroel”, “Israel (Jacob) heard”: he listened, he internalized, and he responded with a complete focus of reunification with the ultimate source of goodness, healing, and power. This is one of the interpretations of Chanukah- “חנוכה” an application (חנו) of the 25 (כה) letters of the Shema.

The Greeks wanted to darken the eyes of the Jewish people. In response the Maccabees rededicate the Temple and brought forth miraculous light. The Midrash teaches that G-d told Israel that once the Temple is destroyed, G-d will desire that we say the Shema, twice a day, and it will be an elevation greater than the sacrifices themselves. That’s the path that Jacob models here: eyes closed, heart open.

The temple for our soul, our Rabbis teach, is in our eyes. This is perhaps why our tradition instructs us to close the eyes of a person, once their soul has returned to its source. However, as long as our heart beats, it must beat for the collective, to see the pain of another’s, as our own.

The temple for our soul, our Rabbis teach, is in our eyes. This is perhaps why our tradition instructs us to close the eyes of a person, once their soul has returned to its source. However, as long as our heart beats, it must beat for the collective, to see the pain of another’s, as our own.

Too often we limit our vision of what we see as possible. When we connect and partner with the Omnipresent (המקום), not only is there comfort but there is a true sense of empowerment. When we look out into the world, whether our heart feels moved to tears or not, we must feel the responsibility to each other, and be willing to make an offering, because of our relationship with G-d.

Today is Rosh Chodesh Teves, the day tradition has it that Jacob is buried. It is also the month that is ruled by the letter “ע” and the power of a deeper sight. We must constantly rededicate our temple, allowing our soul to hear, granting it permission to cry, and letting our tears flow to form a path forward to soothe the pain of all of G-d’s children.

By Rabbi Mike Moskowitz. Sketchnote by Steve Silbert.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] Building A Temple from Tears […]

Comments are closed.