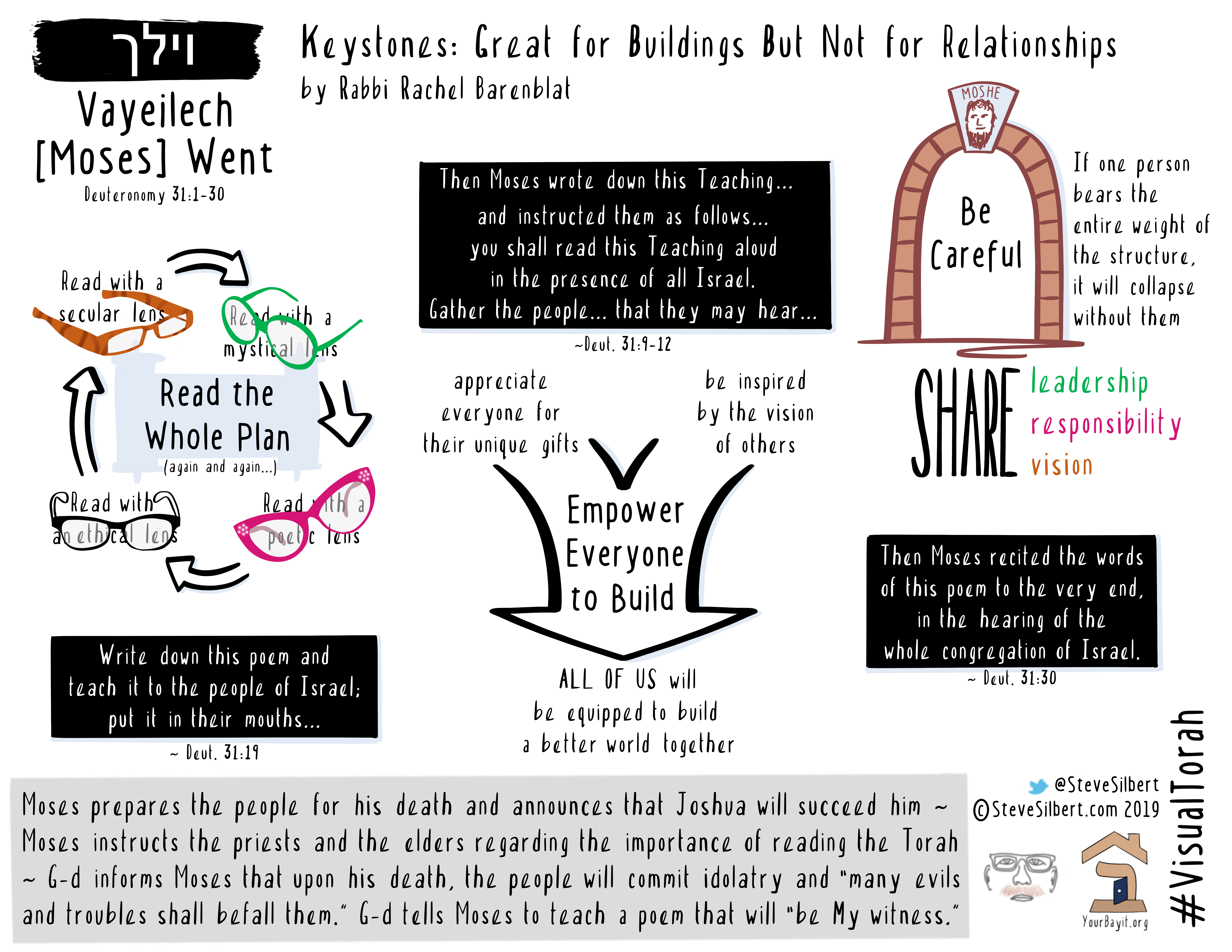

Keystones: Great for Buildings, But Not for Relationships

Part of a yearlong Torah series on building and builders in Jewish spiritual life.

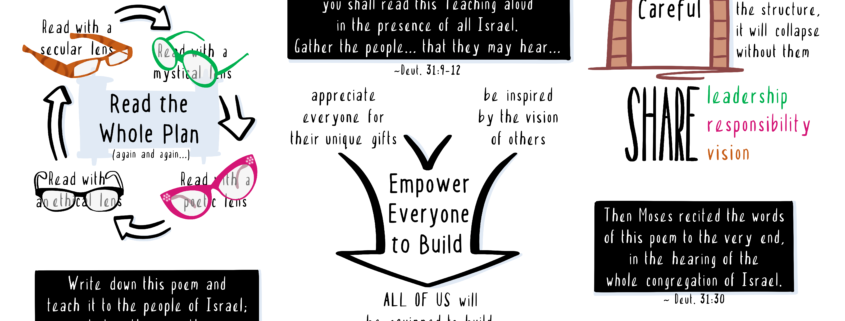

Vayeilech continues Moses’ final speech to the children of Israel, encamped on the banks of the Jordan, preparing to enter the Land of Promise. Three times over the course of the parsha, Torah instructs us to share this teaching (this whole teaching) with the community (the whole community):

“Then Moses wrote down this Teaching… and instructed them as follows:… you shall read this Teaching aloud in the presence of all Israel. Gather the people — men, women, and the strangers in your community — that they may hear…” (Deut. 31:9-12)

“Write down this poem and teach it to the people of Israel; put it in their mouths…” (Deut. 21:19)

“Then Moses recited the words of this poem to the very end, in the hearing of the whole congregation of Israel.” (Deut. 31:30)

Reading these words as this year of building Torah draws to a close, I find two lessons — and one warning! — for us as builders of the Jewish future:

- Read the whole plan

The Jewish mystical tradition regards Torah as a blueprint for all of creation. That poetic image may or may not resonate with us today. But even on a pshat (surface) level, Torah contains all kinds of injunctions about how to live and how to treat each other. Rules like, “remember the day of Shabbat and keep it holy,” or “when you are reaping the harvest of your fields, don’t go all the way to the corners: leave food there for those who need to glean,” or “justice, justice, shall you pursue.” (Or, in R’ Mike Moskowitz’ translation, “Resist so that you may persist.”)

These are Torah’s building instructions for us. They’re the blueprint for building an ethical and spiritually conscious society. And in this week’s parsha, Torah is reminding us that we need to read (and hear) all of them. We may read these instructions through the lenses of Talmud and commentaries. (Indeed, Jews rarely read Torah on its own.) We may read these instructions through a mystical lens, or a poetic lens. But we need to keep reading them, and we need to read all of them — even the ones that may require major reinterpretation to feel live today.

If we’re building a house, we need to look at all of the blueprints: for the foundation and the plumbing, the electrical system and the walls. If we were to ignore the HVAC blueprint, for instance, we’d make some critical errors that would make the house impossible to heat or cool. Assuming that our architect is trustworthy, we need to pay attention to the whole plan. (If our architect isn’t trustworthy, we have a different problem.) Torah teaches that Moshe recited the words of this poem (meaning the Torah itself) “to the very end.” Be attentive to the whole plan.

- Empower everyone to build

When there’s an intention to build together, we need to make sure that everyone is clear on the building plan. We can’t leave anyone out. “Gather the people — men, women, and the strangers in your community,” says Torah. (Today we might regard “men [and] women” as shorthand for “the whole range of genders and gender expressions.”) And don’t leave out the strangers in the community, the outsiders, the immigrants, the refugees. Or maybe we understand “strangers” in a less literal way, as those already in community who aren’t yet on board with the building plan.

The work of building the Jewish future requires all of us. All genders and gender expressions. The insiders and those who feel like outsiders. The locals and the immigrants. A vibrant and meaningful Jewish future can’t be built only by men, or only by white people, or only by Israelis (or Americans), or only by rabbis. On the contrary: this building work belongs to all of us. Only when all of us are present, and all of us are appreciated for our differences and our unique gifts, and all of us are uplifted into service, can we fullfil the blueprint of a world redeemed.

It’s not enough to merely write down “this poem” (the Torah, the blueprint, the building plan) — we need to “put it in [our] mouths.” Everyone needs to be able to take ownership of a piece of the building plan, to speak it in their own words, to articulate for themselves why this building work matters. Even as Torah shows us a top-down hierarchy (God speaks to Moshe who speaks to us), it’s instructing us to pursue empowerment and democratization. It’s instructing us to put the words of the building plan in everyone’s mouths, not just the general contractor’s.

- Be careful…

God says to Moses, “When you die, the people will go astray.” (Deut. 31:16) This may be a warning about excessive verticality. It’s a warning about the dangers of conflating a leader — no matter how extraordinary — with the work they’re leading the community in doing. Every build team needs a leader, to dream and plan, manage and inspire. But if the members of the build team abdicate responsibility, that’s not healthy. Then — to borrow a different architectural metaphor — the leader becomes the keystone, and without them the arch will crumble.

We need to be careful about not vesting too much power in the hands of those who lead. That’s not healthy for leaders, and it’s not healthy for the community, either. Better to share leadership, share responsibility, and share vision with everyone. Empower builders to take up their tools together. When we engage with the whole plan, from bottom to top — and when we each take ownership of the unique building that only we can do (the unique pearl of Torah that only we can teach) — then we’ll be able to build a world of justice and joy, a land of promise wherever we are.

By Rabbi Rachel Barenblat. Sketchnote by Steve Silbert.