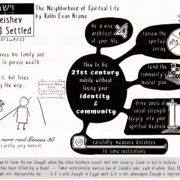

Covenantal Grace / Graceful Masculinity: Lech Lecha

Part of a periodic Torah series on graceful masculinity and Jewish values.

Part of a periodic Torah series on graceful masculinity and Jewish values.

וַיְהִי אַבְרָם, בֶּן-תִּשְׁעִים שָׁנָה וְתֵשַׁע שָׁנִים; וַיֵּרָא יְקוָק אֶל-אַבְרָם, וַיֹּאמֶר אֵלָיו אֲנִי-קל שַׁקי–הִתְהַלֵּךְ לְפָנַי, וֶהְיֵה תָמִים.

When Abram was ninety-nine years old, Hashem appeared to Abram and said to him. “I am El Shaddai; walk before me and be perfect.” (Genesis 17:1)

God commands Abraham to be entirely perfect. It is difficult to perfect one’s body and soul as the partnership between them is naturally contentious. The body is formed from the earth and the soul from Heaven, and each yearns towards its source. Without work, they will be in opposition to each other. This lack of harmony, according to the Sefas Emes, is the deficiency that bris mila, circumcision, comes to fix.1 Circumcision takes a site of physical desire, and consecrates it for spiritual purpose.

The commentators famously ask “If Abraham kept the Torah,2 even though it had not yet been given on Mount Sinai, why did he wait to be commanded to be circumcised?” One simple answer might be that circumcision is more than a physical act. It is the instantiation of covenant. You can’t enter into such an intimate space — the space of covenant — without the consent of the other. Circumcision reminds us of the holiness of actions being determined by the will of another. Until G-d said “I want you …,” it couldn’t be fulfilled.

For bodies to whom circumcision applies, circumcision allies the body to the soul, which provides a continuity of our actions. The temporary nature of the physical world gains permanence through a spiritual attachment. The Bris Kehunas Olam observes an allusion to this in the verse (Psalms 144:4) “ימיו כצל עובר / His days are like a passing shadow.” In Hebrew, the phrase has a numerical value of 484; the same as “body-soul” גוף נשמה. With the sixth letter vuv, “ו” the conjunction “and,” it equals תמים, perfect. The Zohar says the letter “vuv” alludes to the site of the bris milah. The soul is connected and partnered with the body.

The early mystical work Sefer Yetzirah3 writes that there are actually two covenants: a covenant of speech, and the covenant of circumcision. “When Abraham our father looked…G-d made a covenant between the ten fingers of his hands – this is the covenant of the tongue, and between the ten toes of his feet – this is the covenant of circumcision, and G-d bound the 22 letters of the Torah…”

A fascinating observation is made by Ohr Tzvi. The 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet can map to the body. Starting with the toes of the right foot, those letters represent א-ה. The next letter vuv, “ו”, is the “covenant between the toes” or the place of circumcision between the legs. If we continue to count the next five toes of the left foot, these are then aligned with ז-כ. The count then moves to the five fingers of the right hand ל-ע, and then to the mouth which is between the hands, which correlates with the Hebrew letter פה, which actually means mouth and represents the covenant of the tongue. We conclude with the five fingers of the left hand צ-ת. So all 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet are represented on the the body. And this connects the covenant of the tongue with the covenant of circumcision.

The Talmud4 relates that right before Rebbe, the redactor of the Mishna, passed away, “he raised his ten fingers toward Heaven and said: Master of the Universe, it is revealed and known before You that I toiled with my ten fingers in the Torah, and I have not derived any benefit from the world even with my small finger.” Reb Tzodok HaKohen explains this Gemara as a reference to being faithful to the covenant.5

The holiness of circumcision is dependent on speech. The numerical value of פה / mouth is equal to that of מילה / circumcision. King David writes in Psalms “grace/chein is poured on to your lips.” (Psalm 45:3) Perfection of speech requires mastering how to speak, when appropriate, but also mastering when to be silent.6 Noach found grace and was called “perfect” in his generation. He is also praised for his use of sensitive speech.7 However, he was deficient in that he didn’t use language to help those around him to improve themselves and be saved from the flood.

The Magid points out that the measurements that the Torah gives for Noah’s ark: 30, 300, and 50 spell “לשן”, speech/tongue — but the word is missing the “ו”, vuv. Noah wasn’t connecting to others through speech the way he should have, and in the end that manifests in a defilement of his body.8

Correctly using our mouth involves both putting words out into the world through speech, and silence in holding words back. This dynamic of expansion and containment is reflected in the two covenants. Rashi says that G-d’s name E-l Shaddai is the name of G-d used in the passage about circumcision because there is די / dai (sufficient) divinity for all. Yet the Talmud9 relates that the dai in the name E-l Shaddai is also in the context of G-d saying to the creation of the world: “that is enough.” How can the same name of G-d refer both to G-d’s relationship with the world as limitless but also contained?

Chein / grace is produced by expanding the holiness of our spiritual connections, elevating the mundane and each other, while minimizing the physical that could be in opposition with the spiritual. Pursuing perfection comes from increasing our awareness of the Divine Presence, knowing that when we attach ourselves to G-d, we are made for each other.

1. Rashi here shares an interpretation that this verse is referring to the commandment to be circumcised.↩

2. Yoma 28a↩

3. Sefer Yetzirah 6:7↩

4. Bavli Ketubot 104a↩

5. Takanas HaShavin↩

6. Sefas Emes succot↩

7. Pesachim 3a↩

8. Genesis 20:9↩

9. Chagigah 12a↩

By Rabbi Mike Moskowitz.