The Neighborhood of Spiritual Life

Part of a yearlong series about building and builders inspired by the Torah cycle.

Most architects and builders say that where they build shapes what they build. As for physical structures, so for spiritual ones: where we live can powerfully shape our Jewish lives.

My parents chose to make a home in a suburban town that was mostly Jewish, what we endearingly call a shtetl. My public high school was nearly 90% Jewish. The bagel store was next to a kosher deli. Several synagogues were in walking distance of our house. Within our walls were indicia of a Jewish home. Our books were most often written by Jewish authors: Chaim Potok, Philip Roth, Leon Uris. Friday dinner was baked chicken and Sunday dinner was Chinese.

My identity formed by immersion in a community where the ideas and values shared began from Jewish reference points. Yiddishisms helped define relationships, social status informed politics, and everything was measured by what is good for the Jews. In a community so heterogeneous, being Jewish was both comfortable and cautious.

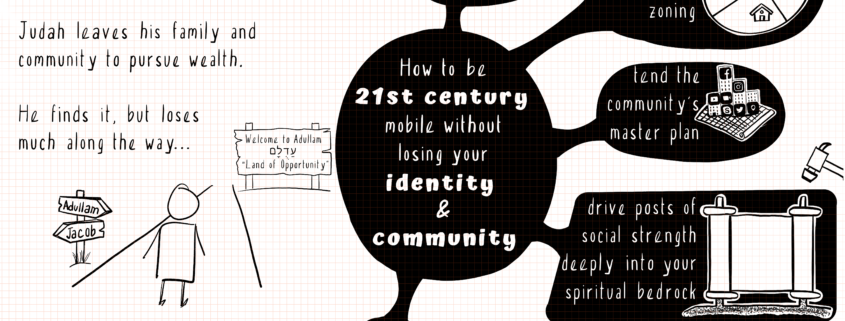

Today fewer progressive Jews experience that kind of close knit community, Outside of Orthodox Jewry, more Jews live in culturally diverse and spiritually depleted communities. Social change is driving a new demographic reality still reverberating through Jewish life: when Jews can live most anywhere, many will live far from communities with strong Jewish centers of gravity. What will geographic dispersion mean for Jewish life? As Jews disperse, what will happen to Jewish community?

We’ve been asking this question for centuries: today’s Jews aren’t the first to move. What can we learn from history’s builders about building on the move?

Finding New Neighborhoods

In this week’s Torah portion (Vayeishev), Judah, son of Jacob, moves away from his family and settles in foreign territory (Gen. 38:1). He takes a Canaanite wife and lives among the Canaanites. Maybe Judah wished to distance himself from his brothers’ awful treatment of Joseph. (Only Judah stood against killing him.) Or perhaps Judah wanted to advance his financial position. To Rashi, Judah and Hirah, an Adullamite, entered into an economic arrangement (Rashi Gen. 38:1), and only then did Judah find a wife and begin raising a family of his own.

Rashi’s explanation resonates. Throughout history, Jews wandered in search of stability and opportunity. Jewish connections as merchants and traders made Jews vital to state economies and planted Jewish neighborhoods around the globe. Today, progressive Jews also make homes based on opportunities, even if opportunities bring them to places with few other Jews.

Judah’s move to a new neighborhood didn’t work out so well. Two of his sons died. He became estranged from his daughter in law. He lived apart from his birth family and without their support. Maybe his move made him wealthy but it offered him little peace or spiritual sustenance.

Jewish history teaches that a thriving life depends on healthy connections that link individuals to what community can offer. Our ancestors knew that vibrant communities were so vital that they limited where Jews can live (Sanhedrin 17b):

A Torah scholar may only live [somewhere] with these 10 things: a beit din (court)…, a tzedakah fund…, a synagogue, a bath house (mikveh), a bathroom, a doctor, a craftsperson, a blood-letter, a butcher, and a teacher of children.

Even 1,500 years ago, our ancestors knew that we can’t depend on ourselves alone. A flourishing life needs justice and charity system, houses of worship and purification rituals, health care, art, quality food, education and more. Only from these core supports can we build strong and vibrant lives. And lest we think that these principles apply only to some, our tradition made clear that everyone can be a “Torah scholar,” so these ideas apply to all. Everyone needs others.

Much has changed in 1,500 years, but not bedrock spiritual principles. More now than ever, we must be wise architects of our lives. We must drive posts of social strength deeply into our spiritual bedrock. We still must tend the community’s master plan, review its spiritual zoning, and carefully measure distances to core institutions. As realtors say, it’s still about “location, location, location.”

But I worry. I worry that as social structures weaken and people scatter, Judaism is losing one of its strongest pillars: a community focus. While Judaism also uplifts each individual body, heart, mind and spirit, Jewish lifeblood is still community. It’s about the interaction between neighbors that we identify as Jewish, like taking responsibility for each other in times of need and meeting at the gym in the Jewish community center. It is about how we host Jewish book clubs and proudly declare our charitable giving on plaques and in synagogue bulletins.

Rapid social change, family dispersion and weakening of community institutions fuel loss of meaning and an epidemic of loneliness. We’re losing not only Jewish neighborhoods but also the Jewish idea of “location” itself.

Rebuilding Jewish Ideas of Location

As technologies continue to reshape every aspect of life, we’ll want to steer their impacts on Jewish ways. We can adapt. When 1950s Jews moved to suburban areas too far to walk to synagogue, the Conservative Movement decided to allow travel by car for the purpose of sustaining a praying community.

Technology is accelerating quickly: science advanced more since 1950 than in the prior 500 years. Today high-speed internet can stream Shabbat services, make virtual shiva minyanim and connect teachers with students anywhere. Whole libraries are instantly available online. E-commerce can ship most ritual items and kosher products anywhere.

So maybe we don’t need to live down the street from the kosher butcher anymore (if we still eat meat), but Jewish life is far more than conveniences and proximity to Jewish institutions. It’s still about Jewish rhythms, values and ideas. How will we, our children and their children experience the rhythms of Jewish living and learn Jewish values and ideas without residing down the street from each other? How will we feel and teach the strength of community if we don’t bring soup to sick neighbors, make shiva calls and build Jewish community centers? Digital connections can be real, but the greatest power of enduring community is the commonplace visceral experience of in person contact.

I don’t have the answers, but I’m not afraid of the questions. We’ll need to figure out how to harness technology to build new “locations” where we all can dwell together in the diversity of communities that we can’t simply turn off. We’ll need to confront technologies and cultural dynamics that disconnect us more than they connect us. We’ll need to learn how to drive the pillars of our lives into Judaism’s communitarian bedrock even when more and more pillars are made of pixels.

I’m also unafraid of the bold experiments we’ll need if they progress alongside personal connectedness. Yes to online talmud study and let’s try virtual minyanim, so long as we will still value our shared in person experiences from attending a chuppah to hosting a Yom Kippur break fast. We just might have to travel a bit further to get there than did our grandparents’ generation.

If we restructure our tradition with an awareness of the benefits of physical community, then the neighborhood of the future will feel every bit like home.

By Rabbi Evan J. Krame. Sketchnote by Steve Silbert.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] The first weeks of Bayit’s Builder’s Blog harvested keystone principles about building the Jewish future – from primordial foundations of building, to where and with whom spiritual neighborhoods create community. […]

[…] The first weeks of Bayit’s Builder’s Blog harvested keystone principles about building the Jewish future – from primordial foundations of building, to where and with whom spiritual neighborhoods create community. […]

Comments are closed.