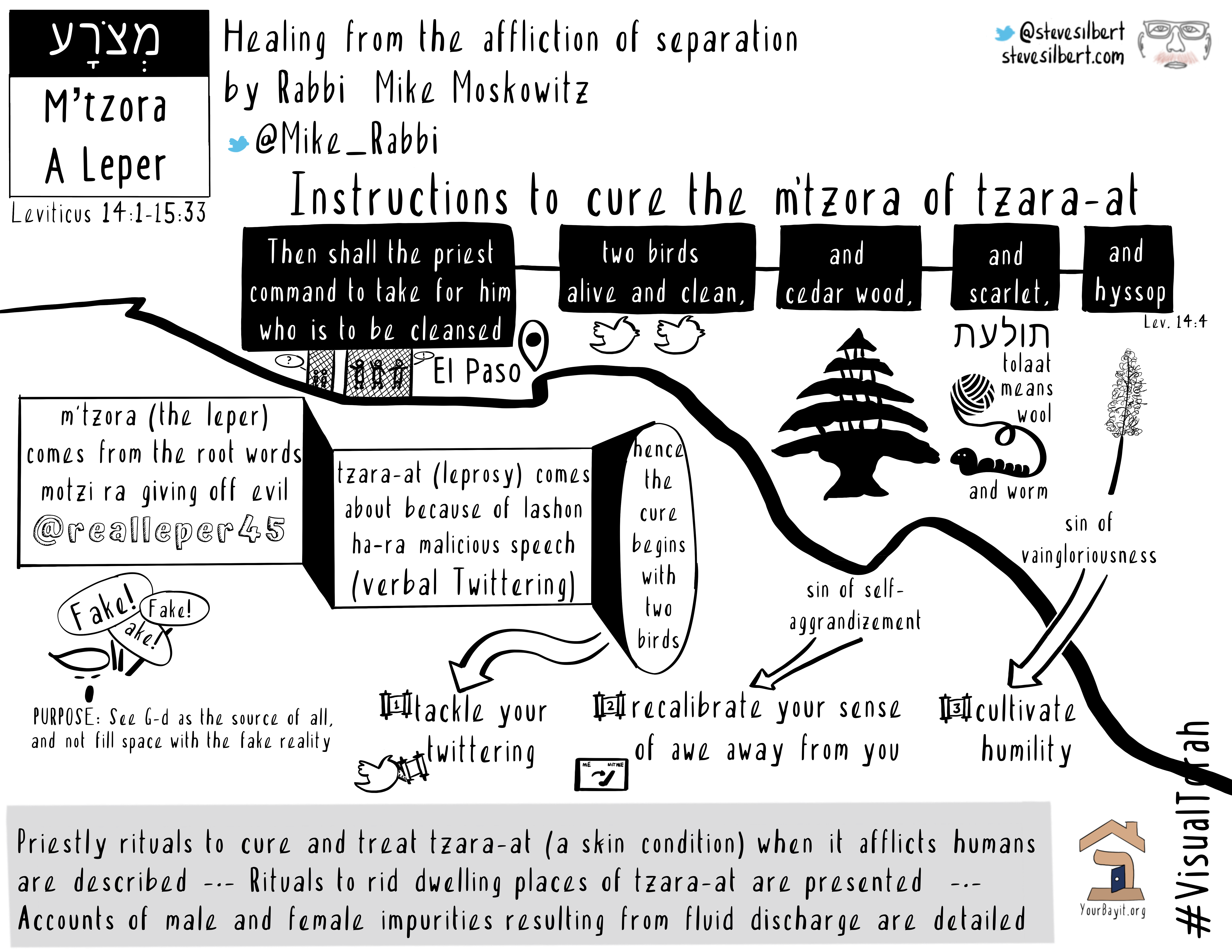

Healing from the affliction of separation

Part of a yearlong series on Torah’s wisdom about spiritual building and builders.

The Talmud teaches (Megillah 31b): “If old men advise you to demolish, and children [advise you] to build, then demolish and do not build, because the demolishing of old men is [as constructive as] building and the building of children is demolishing.” In other words: wise elders can help us see when it’s time to demolish old structures, practices, and ideas that no longer serve — so that the demolishing becomes the first step toward building something new.

I just returned from a trip to the United States / Mexico border co-sponsored by HIAS and T’ruah: the Rabbinic Call for Human Rights. We visited the Otero County Processing Center, which houses over 1000 migrants who have been separated from their families. The refugees housed there have not committed any crime, but the warden referred to them as “inmates.” They wore colored jumpsuits, and slept 50 to a room behind bars. These family separations are connected with the affliction described in this week’s paresha — and in Torah’s cure for that affliction, we can find tools to heal and to build.

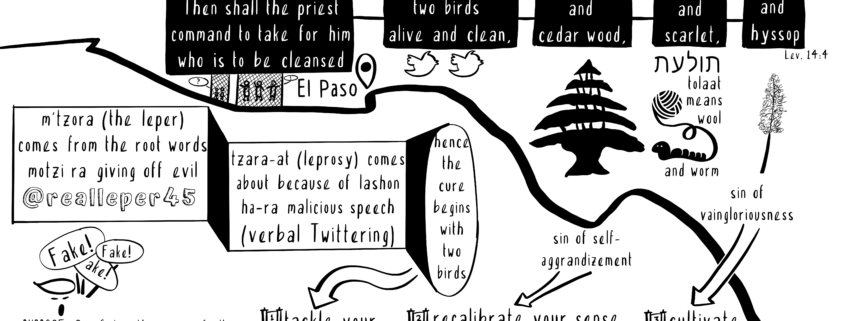

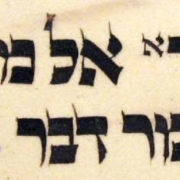

In this week’s paresha, Metzora, we learn that Torah’s cure for the affliction called tzaras (sometimes translated as leprosy) begins with sacrificing birds. Rashi writes, on Leviticus 14:4, “since the affliction [of tzaras] comes about because of lashon ha-ra (malicious speech) which is an act of verbal twittering, therefore for purification Torah requires birds that constantly twitter.” Tzaras isn’t (just) a skin condition: it’s a moral condition, rooted in the sin of malicious speech.

In another interpretation, the Talmud (Arakhin 15b) explains that the word “metzora” (a person with tzaras) can be understood in the language of “motzi ra,” giving off evil. Metzora is when a person’s essence becomes so twisted that whatever that person says or does is bad. The Torah this week provides a roadmap both to the depths of that impurity and the path towards purity.

Our rabbis also say that this affliction of tzaras comes from arrogance. For this reason, Rashi explains, Torah prescribes a cure of cedarwood, crimson wool, and hyssop. “What is the remedy so that one should be cured? He should lower himself from his arrogance like a worm [תולעת / tolaat means both wool and worm] and like hyssop [which grows low to the ground].” And why cedar? According to the medresh (Tanchuma 3) the cedar’s tall magnificence reminds us that the sinner thought of themselves as glorious (and needs to adjust their self-image a bit).

In Talmud (Sotah 5a) we learn that G-d separates from us when we are arrogant — something that doesn’t happen with any other character trait. Our purpose in life is to see G-d as the source of all, and not fill space with the fake reality that we are somehow better than any other person created by G-d. When we are arrogant, G-d pulls away from us. When our eyes are open, we recognize that in our connectedness with each other, we experience connectedness with G-d… and when we separate from each other, we separate from G-d.

The family separations that I witnessed on the border are a profound case of separating from each other. Not only are parents and children separated from each other, but all who take part in creating and enforcing that separation are maintaining a system that separates us from G-d.

The rehabilitation of the metzora, as described in Torah, involves experiencing a temporary separation from community (Leviticus 14:3). We can see that as a kind of sensitivity training. If tzaras is (as Rashi and Talmud teach) an affliction of arrogance and malicious speech, the metzora needs time away from community to do their own work so that they can return with a sense of the communal responsibility that must be at the core of all spiritual practice. Every sin between people creates separation between us and G-d. We need to build in a way that heals that separation — and heals our illusory sense of separateness from each other, too.

As builders of the Jewish future, we must turn away from lashon ha-ra (wicked speech). We must turn away from the temptation of arrogance or holding ourselves to be separate from or better than others. All of these are today’s tzaras — a word that shares its root with tzuris, suffering. Wicked speech, arrogance, and separating ourselves from each other (which means separating ourselves from G-d) are our tzaras and our tzuris — and these are no way to build.

The rabbis opine that the two birds slaughtered at the start of this week’s paresha (Lev. 14:4) can represent two approaches to building a more humble and human society. One approach is to first focus on the greatness of G-d and all of G-d’s wonders, which helps us more accurately calibrate our own greatness. Alternatively, we can start by looking at the loneliness of the human experience. What’s behind our capacity as a people to create terrible separations like those unfolding at the US/Mexico border? Examining that, we should see clearly that the places and policies that come out of lashon ha-ra, arrogance, and separation need to be demolished.

Torah gives us tools: tackling our twittering (let spring’s birdsong remind us to sing the greatness of G-d, not to speak wickedness or untruths), cultivating humility (hinted-at by the wool and the low-growing hyssop), and recalibrating our sense of awe (remembering the majestic cedar). With these we can demolish old structures that serve to separate, and we can build something better in their place.

By Rabbi Mike Moskowtz. Sketchnote by Steve Silbert.