Graceful Shame / Graceful Masculinity: Shmini

.

Part of a periodic Torah series on graceful masculinity and Jewish values.

וַתֵּצֵא אֵשׁ, מִלִּפְנֵי יְהוָה, וַתֹּאכַל עַל-הַמִּזְבֵּחַ, אֶת-הָעֹלָה וְאֶת-הַחֲלָבִים; וַיַּרְא כָּל-הָעָם וַיָּרֹנּוּ, וַיִּפְּלוּ עַל-פְּנֵיהֶם.

A fire went forth from before Hashem and consumed from the altar, the olah offering, and the fats; the people saw and they praised and fell upon their faces. (Vayikra 9:24)

Making mistakes, and learning from them, is part of life. One of the great indicators that we have really begun to internalize the new lesson is that deep feeling of disappointment and embarrassment that we didn’t realize this particular truth earlier, and that we were ever capable of doing the previous thing at all.

This can be a shameful experience that tries to burden us with negativity that inhibits growth and change. There is another, holy variety, of shame called busha, בושה. It propels us towards a more sensitive version of ourselves that just can’t imagine doing that thing ever again. We are simply no longer that person and wouldn’t ever want to be again.

This movement, of coming closer to the ideal, is the act of offerings, korbanot (the word comes from a root meaning to come closer). Rebbe Yehoshua ben Levi taught (TB Sotah 5b) the greatness of being of broken/humble spirits “is as if one has offered all of the sacrifices.”

The parable is given of a beloved prince, who one day rebels and acts inappropriately towards his father the king. As the king deliberates on the correct response, and overcomes his own anger and disappointment with his son, he decides rather than punishing him directly, he will instead advance the prince’s place in the kingdom and afford him even more honor and glory. When the son hears about this generosity, aware in his heart that he truly behaved poorly to his father, he is overcome with busha over his immaturity and can’t even show his face at the dinner in his honor, until he properly apologizes.

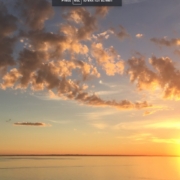

After the sin of the Golden Calf, G-d acted towards the Jewish people with an unending love. G-d so wanted to dwell among the people and bestow goodness that folks were overcome with busha and needed to cover their faces in humility. Rina, the Hebrew word used here, is a unique language of praise; in that it expresses a mixture of happiness and sadness (Rav Tov).

Toras Kohanim says that when the fire descended and consumed the offerings they declared (Psalms 33:1) “Sing joyfully, righteous strugglers, because of HaShem.” It is specifically with “Hashem,” the attribute of mercy, that one can approach G-d from a place of regret, and pain of the past, with gratitude for the opportunity to commit to a different future.

However, the order of the verse is a little strange. Why are they praising G-d before they fall on their faces? If they were really overcome with embarrassment, how did they first sing out before they processed the emotional component?

The Zohar (Mishpatim 108a) teaches that we don’t offer the sacrifices in a vein of the strict attribute of judgment, associated with G-d’s name Elokim, but to the Shem Havayah, the Tetragrammaton. When spelled out יו”ד – ה”י – ו”ו – ה”ה it has the same numerical value as מזבח, the altar, and with the word itself each equal חן, grace.

In the mystical tradition,(Bris Kahunas Olam) G-d’s foundation of grace was revealed through this exchange on the altar and is hinted to by the Talmud (Sotah 47a), that a place, Makom – the Omnipresent – is graceful to its inhabitants.

Perhaps it is the compassion of the place where we are, wherever that may be in the moment, recognizing that G-d is patiently there with us that stirs us to be vocal about our relationship with G-d and give thanks. What follows may be less about a reflection of the past mistake, but more of an attitude towards our future state of being.

After the Ten Commandments were given at Mount Sinai, Moshe tells the people: “Be not afraid; for God has come only in order to test you, and in order that the fear of G-d may be on your faces, so that you do not go astray.” (Exodus 20:17). The Talmud (Nedarim 20a) quotes this verse and declares “זו בושה,” “this is shame,” and posits: “It is a good quality in a person that they are capable of experiencing shame. Others say: Any person who feels shame will not quickly sin.”

Learning more about the way we impact others, through simply being ourselves, is often a painful realization. It can potentially fuel insecurities about being good enough or worthy of being in relationship with others. The Torah is teaching us to reject and replace those thoughts of shame with the commitment to a healthier being. It takes faith and a deep desire for self-improvement to explore the next lesson we didn’t yet know we needed to learn.

By R. Mike Moskowitz.