Hukkat-Balak: Who Is Responsible for Burying the Dead?

Part of an ongoing series that explores Torah through an ethic of social justice and building a world worthy of the Divine.

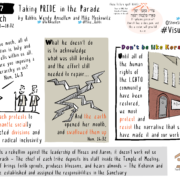

(The Death of Aaron, c. 1896-1902, by James Jacques Joseph Tissot (French, 1836-1902) or a follower, gouache on board, 7 7/8 x 10 3/8 in., at the Jewish Museum, New York)

The custom of family members burying their loved ones is deeply ingrained in Jewish tradition. When the casket (or bier) is lowered during the burial service, the mourners themselves are responsible for covering it, minimally with one layer of dirt. This act is considered a fulfillment of the commandment of k’vod ha-met, honoring the deceased, by returning the body to the earth. Typically, at the conclusion of the service, the mourners leave and the cemetery staff completes the task of filling the grave.

This particular obligation has been on my mind in the month of June for several reasons. Earlier this month I had the honor of officiating at a graveside funeral for a man who died suddenly, leaving his close-knit family utterly bereft. When discussing the order of the service with them, I was surprised to learn of their intention to fill the grave themselves. Two weeks later, the mother of the funeral director of our community’s Jewish Funeral Home was buried by her sons and grandchildren, who solemnly performed their familial duty under the cover of heavy rain. Last week, my spouse and I found ourselves similarly drenched while touring Honey Creek Woodlands, a natural burial ground in Conyers, GA. Thinking about being buried amidst the Pine Forest—my body dressed in plain shrouds and placed gently in a shallow grave dug by hand, covered with the earth and pine needles—laid to rest in the manner of my ancestors, gave me a sense of great peace.

This week, reading in Parashat Hukkat about the death and burial of Moses’ siblings, Miriam and Aaron, I was struck by what is not reported by the narrator. Miriam’s death and burial is mentioned in passing, in a single verse, without any details beyond the time and place:

וַיָּבֹ֣אוּ בְנֵֽי־יִ֠שְׂרָאֵ֠ל כׇּל־הָ֨עֵדָ֤ה מִדְבַּר־צִן֙ בַּחֹ֣דֶשׁ הָֽרִאשׁ֔וֹן וַיֵּ֥שֶׁב הָעָ֖ם בְּקָדֵ֑שׁ וַתָּ֤מׇת שָׁם֙ מִרְיָ֔ם וַתִּקָּבֵ֖ר שָֽׁם׃

“And the Israelites, the whole community, came to the wilderness of Zin, in the first month, and the people stayed in Kadesh. And Miriam died there and she was buried there.” (Numbers 20:1)

Classical and medieval commentators have filled in the story with legends about Miriam’s well, the source of drinking water that accompanied the Israelites in the wilderness due to her merit, and about how the people rebelled against Moses and Aaron after her death. I’ve taught and written about this Torah portion, but until now I never noticed the missing information about who buried her.

Robert Alter, in his commentary on this verse, notes the juxtaposition of Miriam’s death with Aaron’s, suggesting they serve as bookends for the events that transpire between them: “This isolated obituary notice is inserted here to provide a symmetrical frame for the two stories of Moses’s striking the rock and the rebuff of Israel by Edom. Miriam’s death stands at the beginning and that of her brother Aaron at the end.” (The Hebrew Bible, Volume 1, p. 546)

I turned to the end of the chapter to read about Aaron’s death, and found more information there. God tells Moses that the time for Aaron’s death is near, and gives Moses clear instructions regarding the transfer of the priestly garments from his brother to his nephew, Elazar:

קַ֚ח אֶֽת־אַהֲרֹ֔ן וְאֶת־אֶלְעָזָ֖ר בְּנ֑וֹ וְהַ֥עַל אֹתָ֖ם הֹ֥ר הָהָֽר׃ וְהַפְשֵׁ֤ט אֶֽת־אַהֲרֹן֙ אֶת־בְּגָדָ֔יו וְהִלְבַּשְׁתָּ֖ם אֶת־אֶלְעָזָ֣ר בְּנ֑וֹ וְאַהֲרֹ֥ן יֵאָסֵ֖ף וּמֵ֥ת שָֽׁם׃ וַיַּ֣עַשׂ מֹשֶׁ֔ה כַּאֲשֶׁ֖ר צִוָּ֣ה ה’ וַֽיַּעֲלוּ֙ אֶל־הֹ֣ר הָהָ֔ר לְעֵינֵ֖י כׇּל־הָעֵדָֽה׃ וַיַּפְשֵׁט֩ מֹשֶׁ֨ה אֶֽת־אַהֲרֹ֜ן אֶת־בְּגָדָ֗יו וַיַּלְבֵּ֤שׁ אֹתָם֙ אֶת־אֶלְעָזָ֣ר בְּנ֔וֹ וַיָּ֧מׇת אַהֲרֹ֛ן שָׁ֖ם בְּרֹ֣אשׁ הָהָ֑ר וַיֵּ֧רֶד מֹשֶׁ֛ה וְאֶלְעָזָ֖ר מִן־הָהָֽר׃ וַיִּרְאוּ֙ כׇּל־הָ֣עֵדָ֔ה כִּ֥י גָוַ֖ע אַהֲרֹ֑ן וַיִּבְכּ֤וּ אֶֽת־אַהֲרֹן֙ שְׁלֹשִׁ֣ים י֔וֹם כֹּ֖ל בֵּ֥ית יִשְׂרָאֵֽל׃

“Take Aaron and Elazar, his son, and bring them up on Mount Hor. And strip Aaron of his garments and put them on Elazar, his son, and Aaron will be gathered up and die there.” And Moses did as Adonai had commanded, and they went up Mount Hor in the sight of the whole community. And Moses stripped Aaron of his garments and put them on Elazar, his son, and Aaron died there on the mountain-top, and Moses and Elazar came down from the mountain. And all the community saw that Aaron had expired, and all the house of Israel mourned Aaron for thirty days. (Numbers 20: 25-29)

Once more I am confused by the silence of the narrator regarding Aaron’s burial. There appears to be a gap, perhaps an ellipses, in verse 29 where the report of his burial ought to be. At least in Miriam’s case we are told that she was buried, even if we do not know by whom.

I prefer to imagine that Aaron’s closest relatives, his brother Moses and his son Elazar, witnessed his death on the mountaintop of Hor and buried him there, returning his body to the earth and, only after fulfilling their responsibility, returned to the camp to mourn their loss.

Rabbi Gottfried is a member of the Bayit board. Believing the essential meaning of rabbi is “teacher,” Rabbi Pamela Gottfried (she/her) strives in her rabbinate to help individual students of all ages reach their potential. She is delighted to be serving as the Interim Rabbi at Temple Kol Emeth in Marietta, GA while the congregation conducts a search for their next rabbi. Since her rabbinic ordination from the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, Rabbi Gottfried has taught in churches, colleges, community centers, mosques, retreat centers, schools, summer camps, and synagogues.