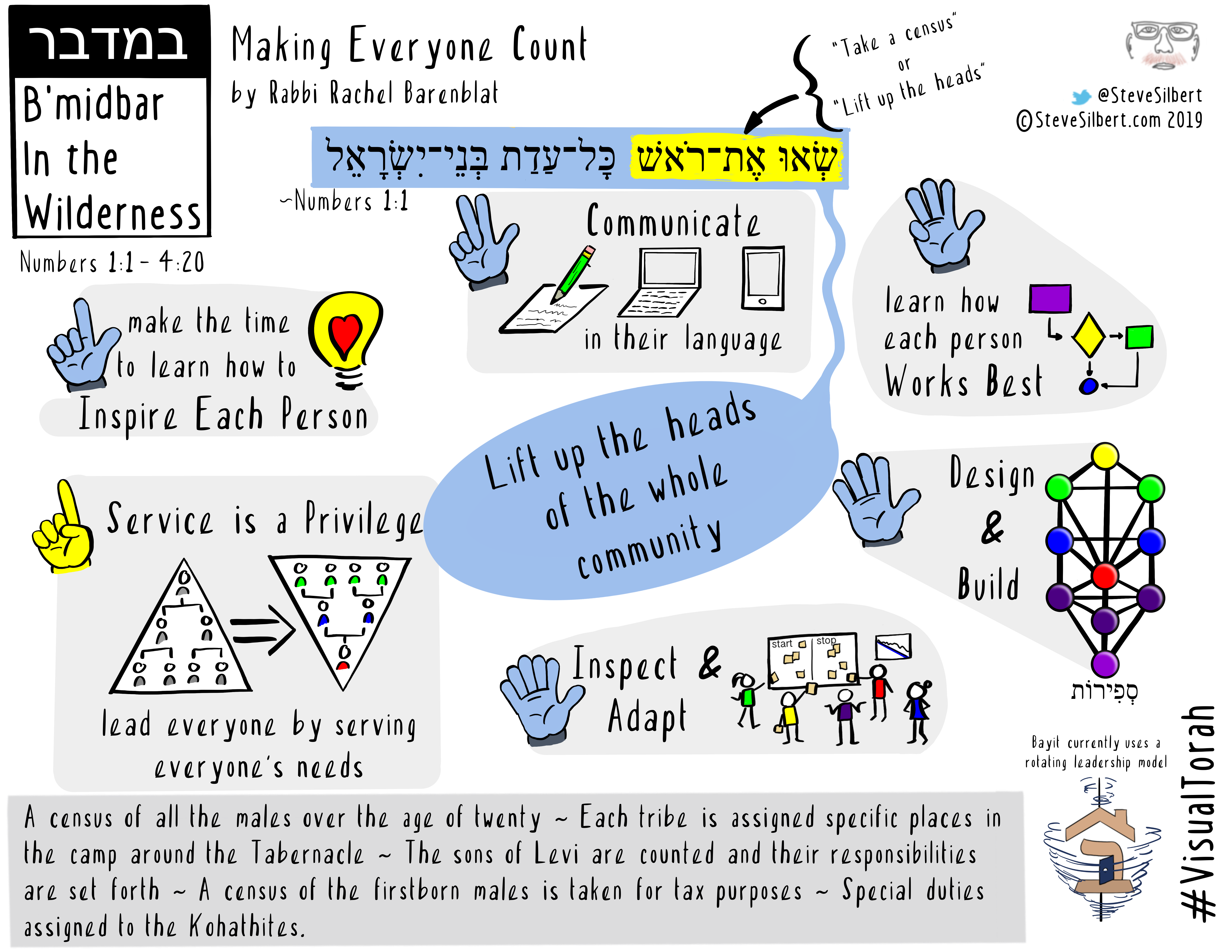

Making Everyone Count

Part of a yearlong Torah series on building and builders in Jewish spiritual life.

The book of Bamidbar (“In the Wilderness”) begins with instruction to take a census. Literally, the Hebrew instructs Moses to “Lift up the heads” of the whole community. (Well, sort of: the original instruction was to lift up the heads of men capable of bearing arms. Today we have different understandings of gender and who counts.)

“Lift up the heads” colloquially means to count people numerically, and also implies uplifting heart and spirit so that everyone counts and knows that they count. This twin meaning has profound implications for building the Jewish future.

In a physical building context, a general contractor must know how many people are on the build team. Even more, she needs to know each individual builder’s talents, and how to uplift each person to best deploy the skills most needed for each building task. It’s a simple pair of instructions that asks heart, care, and curiosity. Who are our potential collaborators? What are their skills and gifts, their passions, the unique contributions to the work that each of these people is uniquely well-suited to make? How can we, in our build teams, “lift up each head?”

We have to really know each other to know what work will most inspire. Is my fellow builder someone who wants a discrete task, or will they best thrive with flexibility and latitude? How do they best communicate? What kinds of things do they like to do, and what kinds of tasks are likely to enervate them — or to energize?

One of Bayit’s grand experiments is a rotating leadership model, in which everyone takes turns serving as chair. This model was inspired by the story of Reb Zalman and the rebbe chair. Reb Zalman z”l used to teach from the head of the Shabbes or festival table — and then invite everyone to rise, move over one seat, and let the next person serve as the “rebbe.” In inviting everyone at the table to sit in the “rebbe chair,” Reb Zalman taught that leadership comes through us, not from us, and that leadership is temporary, not permanent.

One of Bayit’s grand experiments is a rotating leadership model, in which everyone takes turns serving as chair. This model was inspired by the story of Reb Zalman and the rebbe chair. Reb Zalman z”l used to teach from the head of the Shabbes or festival table — and then invite everyone to rise, move over one seat, and let the next person serve as the “rebbe.” In inviting everyone at the table to sit in the “rebbe chair,” Reb Zalman taught that leadership comes through us, not from us, and that leadership is temporary, not permanent.

We evolved our leadership model to uplift values of collective engagement and collective responsibility, balancing collaborative decision-making with clear channels of communication and responsibility. Each of us has the opportunity to step up and then step back. We also built into our system the assumption that folks can “pass” on serving as Board chair if their name comes up in the rotation at a time that doesn’t work well for them.

As we move into our second year of this leadership model, we’re discovering that it doesn’t work exactly as we anticipated. Some folks opted to “pass” on serving as chair for reasons we didn’t anticipate – not only for busy times in work or life, but also because not all of us have the spaciousness to develop the skills and passions to hold responsibility for the whole and help “lift up the heads” of others. Collectively, we recognized that sometimes our passions and talents aim in different ways.

Good leadership asks the person who is leading to really see the people she’s leading. It asks the person who is leading to hold leadership lightly enough that roles and responsibilities can be shared, and to hold leadership strongly enough to give others confidence that there’s a hand at the helm. It asks the flexibility to shift leadership plans and models in response to realities at hand. It asks inner flexibility to step forward decisively and gracefully, then step back decisively and gracefully.

Bayit isn’t alone in this leadership development journey. Every Jewish organization should ask itself hard questions about who should lead, how they should lead, and how best to lift others into leadership. And of course, leadership takes many forms. In a synagogue, for instance, there’s likely to be any number of roles – whether rabbi, cantor, education director, executive director, board chair, board treasurer, fundraiser, etc. — plus other roles that don’t necessarily have titles: community elders and sages, “den mothers,” angel donors, cleaning crews and more.

In Jewish mystical tradition, God is One and is manifest in the world through ten sefirot, qualities such as lovingkindness, boundaried-strength, and balance. Each of those qualities is different, and each one is necessary. What would happen if every Jewish organization approached organizational development through that lens — ensuring that every leadership structure has and balances a diversity of skill sets and qualities, each integral to the whole?

Moses knew that community leadership is also community service. He knew that community leadership requires really seeing the people whom one is privileged to serve. It’s easy to imagine leadership vertically — the leader is at the “top,” and everyone else is at the “bottom” — but the servant-leadership model inverts that hierarchy.

God’s first instruction to Moses this week is to take an accounting of who’s in the community, to uplift each soul for who they are and what they bring to the table. In the Jewish community and in the world, we need to recognize who each of us truly is and how each of us is best called to serve. That’s the only way to build a Jewish future stronger and more whole than the sum of its parts.

By Rabbi Rachel Barenblat. Sketchnote by Steve Silbert.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] a theme from last week’s portion (Bamidbar). It also continues my colleague Rachel Barenblat’s Builders Blog teaching that Torah’s instruction to take a census meant lifting up each person’s role and gifts as […]

[…] Here’s Torah commentary at Builders Blog (a project of Bayit: Building Jewish), this week written by Rabbi Rachel and sketchnoted as always by Steve Silbert: Making Everyone Count. […]

Comments are closed.