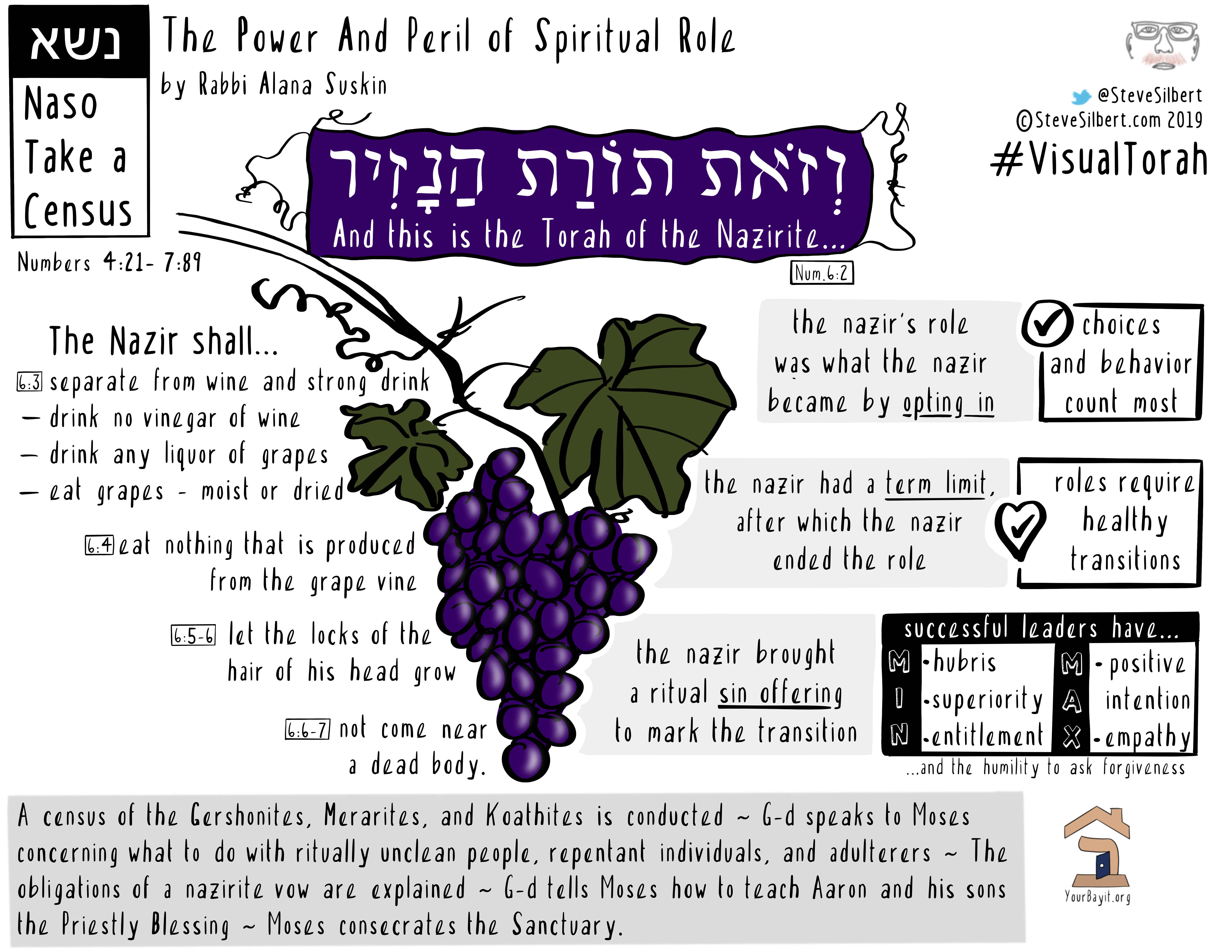

The Power and Peril of Spiritual Role

Part of a yearlong Torah series on building and builders in Jewish spiritual life.

As we all build the Jewish future, how sure should we be about what’s holy? Asked that way, maybe the question answers itself: only one filled with hubris would proclaim knowing for sure what is holy.

And yet, Jewish spiritual life – and Jewish spiritual pathways of role, halakhah, liturgy and community – all send clear signals about what is holy and what is not.

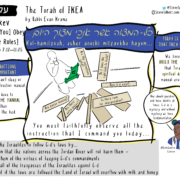

What’s up with that seeming inconsistency, and how do we build for it? That’s the question I take from this week’s portion (Nasso) and its three roles of sotah, nazir and kohen.

This role focus continues a theme from last week’s portion (Bamidbar). It also continues my colleague Rachel Barenblat’s Builders Blog teaching that Torah’s instruction to take a census meant lifting up each person’s role and gifts as fellow builders of that era’s Jewish future. In a shared leadership model, people step forward and step back each in their right time. No one person is entitled to lead, or ever should lead, based on identity or fixed role.

Nasso continues to explore spiritual roles assigned to different kinds of individuals. The portion starts with three subcategories of Levites and divides their labor based on tribe, then jumps to persons whose roles are shaped by actions.

First is the sotah, a woman whose husband has no evidence that she was unfaithful but who nevertheless is jealous. Torah instructs him to bring her to the kohen and put her through a humiliating public ordeal to prove her fidelity.

Next is the nazir, who takes on themselves a period of abstinence. The nazir is not to drink wine or vinegar, or eat grapes or raisins. They also abstain from trimming hair or going near a corpse – even for a close family member.

Finally, the kohen receives the power to bless the people with what we know today as the Kohenic (or Priestly) Blessing.

The sotah and kohen are mirror images of each other. Each receives a role to transmit holiness by action. The ancient kohen was male and his society understood him to be holy inherently, based on who he was. By sharp contrast, the sotah was a woman and her society understood her to be holy only as she served others. The sotah’s holy “service” was to undergo a public ordeal to “prove” her fidelity, assuage her husband’s jealousy, and give the community and its leaders a way to ritually determine truth under social and emotional stress.

The sotah lacked power. A jealous husband brought her to the community’s highest power for a ritual that publicly humiliated her and would even kill her if she was “proven” unfaithful. On the other hand, the tools of the sotah trial – dirt, water, a little dried ink – were highly unlikely to have a negative physical effect on anyone, regardless of guilt or innocence. Thus, even if the sotah ordeal “fixed” the problem of a jealous husband, it did so without fixing the real “problem” of the woman’s powerlessness.

Compare her to the kohen – male, born with power, automatically given an identity entitling him to serve at the community’s highest levels of perceived holiness. By virtue of birth, he decided who stayed in camp and who was sent out. He tested the sotah, offered the sacrifices, purified the impure and blessed the people. The kohen declared what was holy, by virtue of his identity.

Tellingly, however, Torah offers not only the stark contrast of sotah and kohen, but also a third role, the nazir, relative to them both. It is in the nazir that Torah offers the most healthy model for building the spiritual future.

Unlike the sotah who had status foisted on her, the nazir positively acted to take on his or her role. And unlike the kohen whose role was given based on identity, the nazir’s role was what the nazir became by opting in. The nazir wasn’t anything on account of birth: the whole point of the nazir was the choice to become one and behave as one.

The opting-in aspect of a nazir teaches us that people who willingly choose holy roles, and abide their limits, merit special consideration to the extent their behaviors align with the status and role they purport to choose. A nazir who didn’t take on the self-imposed limits of the role wasn’t really a nazir. Far more than role or title, choices and behavior count most. This idea is especially compelling today, when all sacred belonging is, ultimately, chosen, but this should not cause us to take it less seriously. Such choices are powerful: once made, we should consider these choices as having inherent and compelling worth.

The nazir also teaches that roles, and especially roles of power for spiritual building, require healthy transitions. The nazir role had a term, a period of time, after which the nazir ended the role. At the end, the nazir brought a ritual offering to mark the transition. Even more, the ritual offering was a sin offering, as if to imply that the nazir role never could be inherently pure.

As for the nazir, so for all who take on a spiritual role. No spiritual role can be perfectly held, if only because we are human. As for the nazir, a spiritual leadership role will need a sin offering when its term ends – whether because we began the role with hubris, or the role aroused in us a sense of superiority, or we held the role with less than full diligence, or we achieved less than we intended, or we cause harm along the way (whether deliberately or unintentionally).

To be a nazir is to take on a role that requires a sin offering. It is to be unsure – and this lack of certainty is the nazir’s third and maybe most important lesson of all. Unlike for the sotah and kohen, about whose roles Torah was very clear, Torah is at best vague about what made the nazir holy. And if Torah was vague, textual tradition was downright confused about what it meant for the nazir to choose.

Was a nazir holier than others who didn’t choose the role (B.T. Taanit 11a; cf. Ramban, Maharit: Shealot U’teshuvot 1:543)? Or was a nazir less holy for abstaining from things that were permitted? So suggests Robert Alter in his 2004 Torah commentary: A nazir, by “acting exceptionally to set oneself apart for holiness, renouncing the pleasures of wine and letting one’s hair grow long, expresses a kind of presumption, an aspiration to spiritual superiority, and thus is an offense” (see also B.T. Taanit 11a; B.T. Nedarim 10a; Rambam, Shemonah Perakim). Or maybe a nazir chose the role as a spiritual regimen of self-restraint, sensing that they themselves needed it (see Nechama Leibowitz, citing Astruc, Midrashei HaTorah; Rama on B.T. Sotah 2a). Or maybe the nazir represented an aspiration for the whole community rather than just oneself (Bamidbar Rabbah 10:11)?

All are possible – and maybe unavoidable for everyone who builds the Jewish spiritual future. And that is exactly the point.

In that sense, everyone who steps forward to build the Jewish future is a nazir – and we should treat them that way. We must attract, train, and treat our spiritual builders not as intrinsic (like a kohen) and we should certainly not want them to be coerced (like a sotah), but as people who choose voluntarily – and temporarily. We must regard the role as tempered by strictures of time, character and self-restraint. We must know and accept that these strictures will be honored imperfectly, and therefore build into the role transitions for repair and re-integration.

If we don’t, then our sacred institutions – and the Jewish future – will continue to distribute power in sometimes very unhealthy ways, perpetuating a status quo based on identity or disempowerment that can leave the vulnerable more vulnerable.

By contrast, with a nazir approach to spiritual building, we can aspire to high standards with healthy ambivalence about fully achieving them – not to arouse mistrust or cynicism, but to harness the inner wisdom and outer structure that are the keys to effective spiritual design.

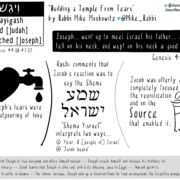

By Rabbi Alana Suskin. Sketchnote by Steve Silbert.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] Here’s Torah commentary at Builders Blog (a project of Bayit: Building Jewish), this week written by Rabbi Alana Suskin and sketchnoted as always by Steve Silbert: The Power and Peril of Spiritual Role. […]

Comments are closed.