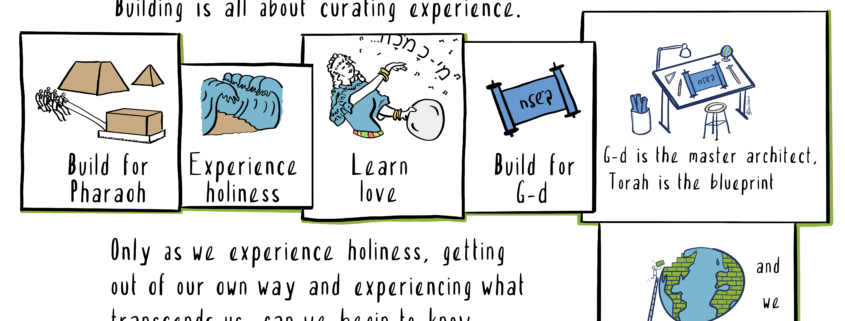

Building (For) God

Part of a yearlong series mining Torah’s wisdom about spiritual building and builders.

It’s a heady and awesome thing to “build for God.” That’s what spiritual builders do. That’s the business we’re all in.

We can do it well (our ancestors’ desert Sanctuary), or we can do it disastrously (the Golden Calf) – but either way, building for God is what collective spiritual enterprise is at least partly about. Whether places, structures, systems or relationships, we build so that through them we can experience a bit of the sacred right here on Earth.

And if you think you’re not a spiritual builder, or that your spiritual building isn’t about experiencing the sacred where you are, look deeply into this week’s Torah portion (Beshallach) and think again.

Our slave ancestors, freed from Egyptian bondage, reach the Sea of Reeds and miraculously walk through. Leaving Pharaoh’s army behind, our ancestors break into song. What they sang, heard with modern ears, is revolutionary.

Traditionally we understand their “Song of the Sea” (Exodus 15) as a celebration and an affirmation. At the Song’s heart is the exclamation, Mi chamocha ba’eilim YHVH (“Who is like You, God?”): Who else could split the sea and overpower the world’s strongest army to free the bound? These words have echoed in Jewish hearts ever since.

But there’s more. Freed from seemingly endless bondage building brick structures for an enslaving Pharaoh, they sang: “In Your love, You lead the people You redeemed; in Your strength, You guide [us] el-nave kodshecha (אל נוה קדשך) – to Your holy abode” (Exodus 15:13). Instinctively they knew that wherever they were going, they were being led to a place – and that the place was holy.

What does this have to do with spiritual building? Just moments earlier, they also sang: Zeh Eli v’anvehu (זה אלי ואנוהו) – “This is my God whom I’ll adore” (Exodus 15:2). The two phrases share the same word (nave), which hints at a deep meaning: “This is my God whom I’ll build into a holy abode.”

Take that in. In liberation’s peak moment of ecstatic joy, they sang not only that they were headed to a holy place but that they themselves were going to build it. What were they going to build? Not only would they build for God: they would build God! And why would they build? They’d build so that they could “adore God.”

Our ancestors – who had been builders under Pharaoh’s lash – now would become builders for God. And by building, they would learn to love. We learn that freedom is not for its own sake but for a loving purpose: to build for God, and to build God.

Of course, our wandering ancestors’ first spiritual building went very wrong: their first attempt was a Golden Calf that they treated as God. That’s the danger of venerating things (whether places, structures, systems or relationships), and venerating our own capacity as builders. Maybe that’s why God had to get exactingly clear: “Build Me a Sanctuary so I can dwell in them” (Exodus 25:8) – not “it.” God dwells in us all.

By building the right way, divinity can flow through the builders. We learn that holiness and the spirituality of building are not about building except as building focuses human awareness and human actions on holiness.

So what should we make of our ancestors’ “build God” idea?

Jacob got it in his peak experience of wrestling: “God was in this place and I, I did not know” (Genesis 28:16). In a peak spiritual experience, we know that everything pulses with divinity, that there is nothing but God, that we (as builders) are instruments of the sacred. It’s precisely by not knowing ourselves, not getting stuck on ourselves, that our awareness clears enough to really get it.

Same for our ancestors at the Song of the Sea: in that peak experience, it was all God.

Great ideas, but so what? What do they really mean for us here and now as builders? To us, we learn a few things:

- Building is all about curating experience. The idea of God is not God; the thought of the sacred is not the sacred. Only as we experience holiness, getting out of our own way and experiencing what transcends us, can we begin to know God through any place or thing. Thus, every spiritual building, to be worthy of that name, must curate experience beyond oneself.

- Builders need to hold on gently, and maybe not at all. Every spiritual building evokes a Zen-style koan. Even as we “build God,” we can’t ever “build God” because God is never in a thing: “Build Me a Sanctuary so I can dwell in [you].” Lest our spiritual structures and systems become like Golden Calves, we must see them only as conduits, only as effective as what they channel. And because we humans tend to grow attached to our own handiwork, we must constantly remind ourselves and each other that what makes spiritual building spiritual is precisely that we hold it gently and maybe not at all.

- We must test our buildings and sometimes let them fall. If spiritual buildings are only as effective as what they channel, then a building that doesn’t channel isn’t worth keeping. We must test our spiritual buildings (places, structures, systems and relationships), repeatedly asking what they’re channeling now. And if they’re too clogged, or not transmitting holy experience, it’s time to redesign and rebuild.

God is the master architect, Torah is the blueprint and we – all of us – are builders. It’s our calling – all of us – to build wisely, courageously and well. And if we do, we too can become vessels for holiness in the world.

By Rabbi Bella Bogart and Rabbi David Markus. Sketchnotes by Steve Silbert.