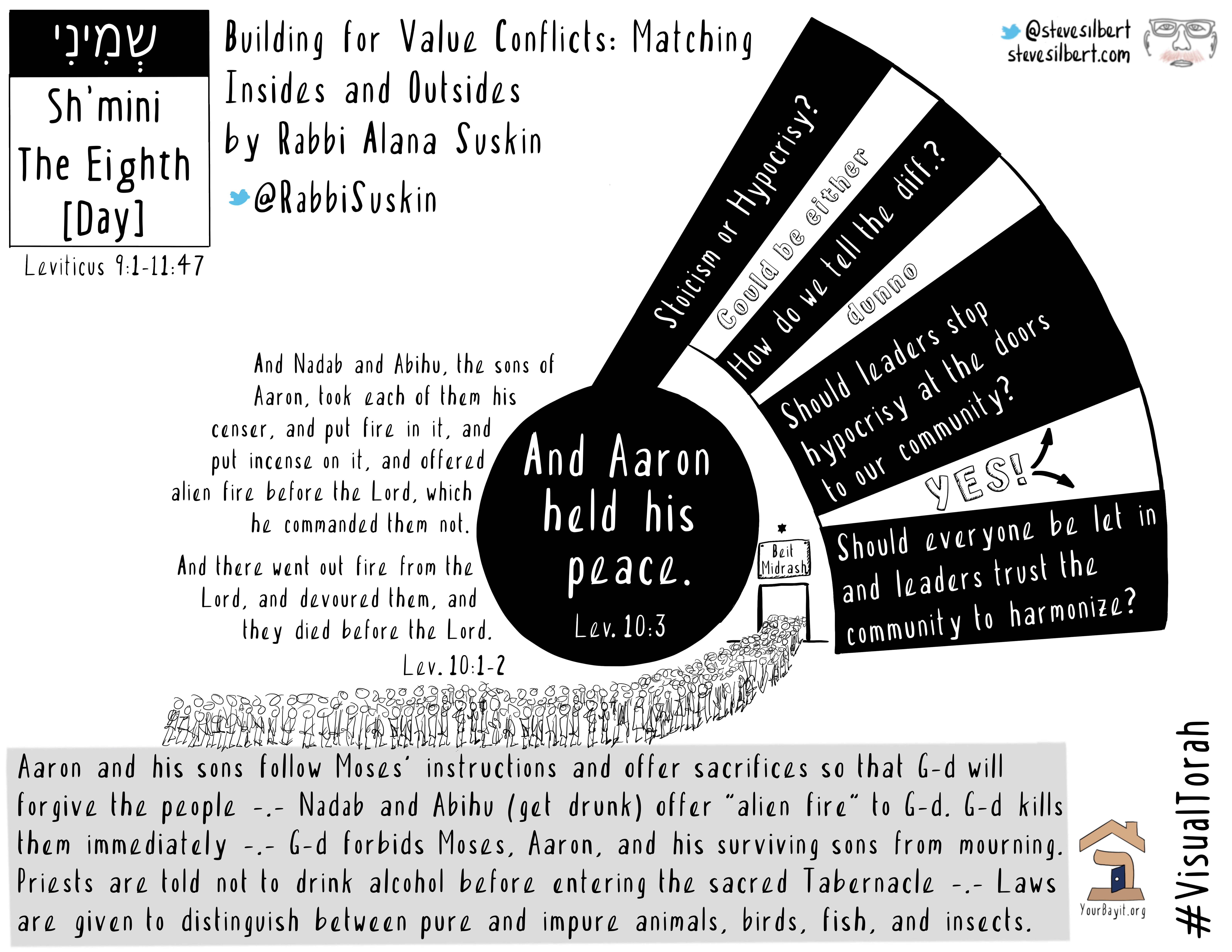

Building for Value Conflicts: Matching Insides and Outsides

Part of a yearlong series on Torah’s wisdom about spiritual building and builders.

We build institutions and communities to support values, but buildings don’t live values: people do. What if values conflict, or we struggle to align our feelings, values and behaviors?

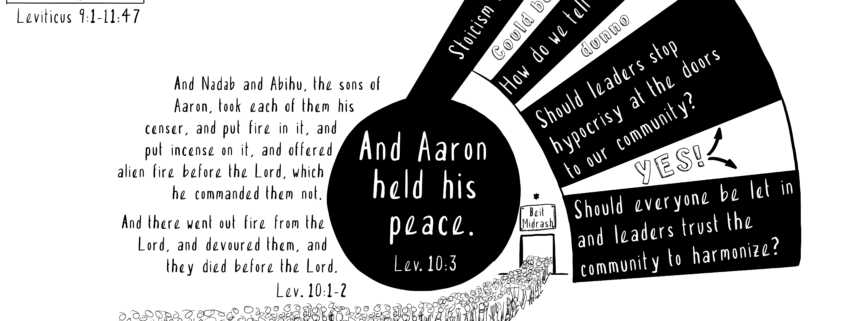

These are questions of the tragedy that opens this week’s Torah portion (Shmini).

Aaron’s sons, Nadav and Avihu, offer God an esh zara (“alien fire”), causing their deaths. As Aaron’s sons lie dead before him, Moses speaks – perhaps in an attempt to explain their deaths – of God’s glory. Aaron is silent.

We can only imagine what Aaron thought and felt, and many commentators have tried. Whatever Aaron felt, it is almost certain that his outer stoicism masked inner anguish. Was Aaron a hypocrite, or caught between fatherly emotion and priestly role? How difficult it must have been to align his inner life and outer commitments.

Conflicts between inside and outside are among humanity’s greatest challenges. Sometimes conflicts between emotions or desires and behaviors, or between values, can lead us to act in ways that are corrosive to community or our own souls. But conflicts between inside and outside also are inevitable: humans and institutions are complex and flawed, and integrity is difficult to achieve even with our best efforts.

Even as each of us personally must seek our own integrity, Jewish life especially values communal integrity. What if institutions’ values and behaviors conflict? Can spiritual institutions and buildings be hypocritical? When do they require correction? When value conflicts arise, when does challenge represent correction and when — in the imagery of this week’s Torah portion – do they become “alien fire”?

And when these conflicts arise, how should communities handle them? Should leaders stop “alien fire” at the proverbial community door by screening people and practices, or should we trust community to harmonize whatever comes in? Should we set values from the outside, or from the inside?

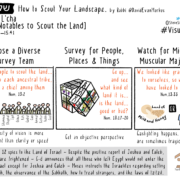

The Talmud (Berakhot 28a) offers two ways to approach these questions. Rabban Gamliel, head of the study hall, stationed a guard at the door to tell people: “Any student whose inside is not like his outside (ein tocho k’varo) will not enter the study hall.” He was replaced by Rabbi Elazar ben Azaria, whose first act was to dismiss the guard at the door and open the study hall to anyone. So many students came that the study hall had to add 700 benches.

Rabban Gamliel took an “outside” approach. He let in only people whose outsides already “matched their insides,” thereby protecting the institution from people who he believed to fall short. This week’s Torah portion affirms this approach partly, calling us to “distinguish between the sacred and the profane, and between the impure and the pure” (Lev. 10:10). We protect what is precious from harm. But the cost can be high: we risk screening out people poised to grow, and people who might offer needed challenge to strengthen our institutions.

Rabbi Elazar took an “inside” approach. He felt that community immersion would align each student, so each person’s inside would be (or become) like the outside. Trusting the building and all within it, Rabbi Elazar flung open the doors – even at risk of letting “alien fire” enter. To Rabbi Elazar, ein tocho k’varo wasn’t the end of the matter but potentially only part of a process. Not a fixed judgment of unfitness, ein tocho k’varo became a chance for growth for the individuals who joined the community.

Both approaches have their place. Like insides and outsides themselves, we must balance Rabban Gamliel’s outside approach and Rabbi Elazar’s inside approach. We must build for both, so neither one becomes excessive.

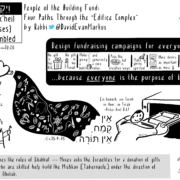

This middle path reflects the Talmud’s one other mention of ein tocho k’varo, which arises in the literal context of building the Mishkan. Commenting on Torah’s instruction that the Ark be made of acacia wood and then “cover[ed] with pure gold, inside and outside you will cover it,” (Ex. 25:11), Rava said that likewise, anyone whose “inside is not like his outside …cannot be considered a Torah scholar” (Yoma 72b).

Rava echoes Rabban Gamliel: make sure people are gold inside and out before they enter. But however golden the Ark would become, first it was built with wood. One might even say that at its deepest level, the Ark’s wooden inside is not like its outside, and perhaps cannot be. Still, we must act to cover both inside and outside with gold.

Jewish life is about not only who we are but also how we act, and how we learn to be. Like covering the Ark with gold both “inside and outside,” we must lay the gold of values “inside” and then live them “outside.” And like gold on an Ark or wisdom in a study hall or spiritual attainment in our lives, it’s a process of layers – and we must build for it.

What of today’s synagogues and other Jewish spaces? We learn that we must ask about our communal spaces the same question Rabban Gamliel asked about individuals: are their insides like their outsides?

How many synagogue websites describe themselves as heimish (warm and welcoming) but newcomers receive no warm welcome? How many Jewish institutions claim to fulfill Jewish values while not paying workers living wages or treating staff more like wood than gold? How many leaders who stand at the door are ein tocho k’varo – saying one thing but acting differently in private?

In countless ways large and small, institutions – sometimes precisely because they’re institutions with their own internal dynamics – can become ein tocho k’varo. And when they do, they fail inherently to achieve their missions.

Rabbi Elazar’s “inside” approach taught that the timeless internal strength of a healthy beit midrash (house of study – today a seminary, school or other learning institution) is its openness to refine, teach, and propagate values. Therefore, we must not guardi the doors too closely – whether literal doors or the doors to ideas – and we must be as truly open and welcoming in reality as we purport to be in name.

But Rabban Gamliel’s “outside” approach wasn’t wrong. Institutions are vulnerable to hypocrisy. Sometimes we need someone standing outside to speak difficult truths – whether to people coming in, or to people already inside.

We must build for both Rabbi Elazar’s inside approach (flexibly for learning and inner transformation) and Rabban Gamliel’s outside approach (strongly for sorting and boundaries). Prominently post core values so all can see them. Make sure build teams and leadership teams have both a Rabban Gamliel (calling people out) and a Rabbi Elazar (calling people in) – with two ways to evolve insides and behaviors to match outside claims.

And like the Ark, teach that everyone begins as wood and, at least potentially, can become gold inside and out.

By Rabbi Alana Suskin. Sketchnote by Steve Silbert.