Nasso: On PaRDeS and Speaking Out Against Judgmental Literalism

Part of an ongoing series that explores Torah through an ethic of social justice and building a world worthy of the Divine

As we prepare to celebrate the month of June, which is designated Pride Month in honour of the Stonewall Uprising, it is especially important to reflect upon the ways that literal readings of the Bible about gender and sexuality have caused… and continue to cause… deep harm. People’s lives are at stake. The commandment to engage with our Hebrew text in a Jewish (non-literal way) is a form of “Pikuach Nefesh” (saving lives).

The rabbis teach that the placing of any religious commandment above the risk to human lives is a form of idolatry, because the Torah was given to us as a tree of life. The reading of the biblical text in a literal manner is a form of idolatry with dangerous consequences. In the face of growing threats to civil liberties, and to the democratic process itself, it has never been more pressing to think critically and place the sanctity of life as frontlets between our eyes, that it may serve as a guiding hermeneutic.

By revisiting this week’s Torah portion, which contains the disturbing description of “sotah” (the testing of a woman’s sexual fidelity), it is especially important to learn how to queer our understanding of the two-dimensional text we inherited, and use that to inform our thinking and actions. To support a contemporary organisation that seeks to celebrate these important strategies for a modern world check out: https://svara.org/.

As we face a growing threat of judgmental literalism and religion is increasingly weaponized, this approach to textual study is more important than ever.

The Torah portion of Nasso (Bamidbar/Numbers 4:21 – 7:89) contains a seemingly unrelated and troubling series of stories. It begins with the “headcount” (=nasso) of the Children of Israel as they transport the Mishkan (tabernacle). This seemingly mundane accounting is then followed by the disturbing account of the “sotah” which we are told is the way one should punish a “wayward woman” who has been unfaithful. This story is then attached to the story of “nazir” who is described as someone that creates unnecessary religious prohibitions for themselves, such as forswearing off wine or cutting their hair. The priestly blessing then follows.

The early rabbis of the Talmud taught that one should examine the context and connecting themes of seemingly disparate biblical stories. A further technique suggests that we examine the Hebrew grammatical roots of words to see beyond the literal. These principles of interpretation are included in our daily prayers as a constant reminder to never be satisfied with concrete understandings of biblical text.

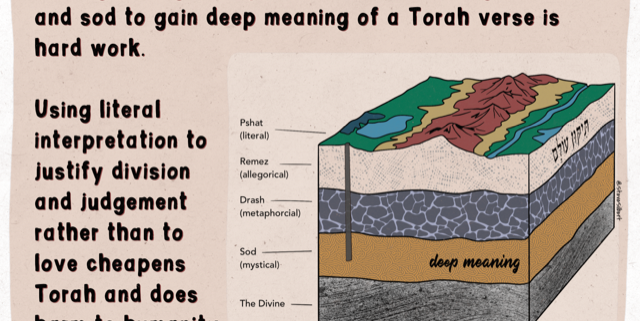

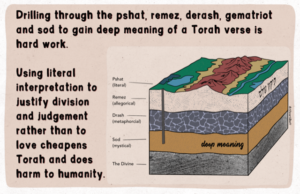

According to rabbinic tradition, there are four levels of biblical interpretation: Pshat (literal), Remez (hint to application in our own day), Drash (ethical or moral) and Sod (mystical or spiritual). Often, the literal translation of the text is exactly the opposite of the deeper meaning that the Torah seeks to convey. This counter-cultural approach to biblical interpretation is desperately needed in many so-called “religious” circles of our own day.

According to rabbinic tradition, there are four levels of biblical interpretation: Pshat (literal), Remez (hint to application in our own day), Drash (ethical or moral) and Sod (mystical or spiritual). Often, the literal translation of the text is exactly the opposite of the deeper meaning that the Torah seeks to convey. This counter-cultural approach to biblical interpretation is desperately needed in many so-called “religious” circles of our own day.

One way to understand the seemingly disparate stories in Nasso is to see the possible causal connections between them. The carrying of the Mishkan (tabernacle) can be understood as a cautionary tale for how to adapt our understanding of G!d in our own journey through the wilderness: if we content ourselves with a literal understanding of the text, then the judgment, violence and false piety of these stories will become our burden to carry.

The Children of Israel were carrying the literal tabernacle. Exodus 25:8 clearly states that when the Children of Israel built the sanctuary, G!d promised to dwell “in them” not “in it”. It was the act of working together to build it that made it holy. Yet, they carried the physical tabernacle with them, rather than rely on the ways that G!d had come to dwell in them and in their relationships with one another. Perhaps it was a result of the intergenerational trauma that they had experienced in Mitzrayim (ancient Egyptian bondage) that led to this reliance on objects rather than people.

The Hebrew word “nasso” literally means to raise up or elevate. It is used to refer to the counting of the children of Gershon. The Hebrew word “gershon” has the root “ger” which means both “stranger” and also “one who dwells”. This same word has contradictory meanings, as indeed does this whole passage. To assist us in selecting one interpretation over another, the word “gershon” is further related to the word “gerush” which means to divorce or separate one’s self. The deeper meaning of this biblical passage is the danger of elevating oneself or separating one’s self from others… When we look at those who dwell with us and see them as strangers, violence will ensue.

Using this hermeneutic lens, these connecting stories contain a deep critique of the ways that religion can be weaponized when we objectify people. The story of “sotah” is a story about the power of judgment: the sexuality of the “wayward woman” is demonized and a vicious and violent outcome is described. While a misogynist society has enjoined us to read this to be a consequence to the “sotah”, a more compelling interpretation would suggest that violence is the outcome of objectification and a judgmental religious fundamentalism.

Similarly, the story of the “nazir” who foregoes the pleasures of life can be read as a critique on an ascetic pietism that fears sexuality. The biblical text notes that the “nazir” is required to bring two sacrifices to atone for having taken such a vow (Numbers 6:11). Holiness is not about asceticism. Modern psychology would further explain that such repression can lead to defense mechanisms such as projection or reaction formation, of which judgment is one example.

The story of the “nazir” is actually a commentary on the story of “sotah,” where both extremes are reflective of the false binaries that are caused by the splitting defense of the ego. Both can be seen as the consequence of the word “nasso” where one person is lifted up at the expense of the other, leading to “gerush” (separation or splitting) becoming idealized over unity.

This approach to faith is at the core of what is increasingly recognized to be a form of “adverse religious experience”. Sadly, this type of religiosity is increasing in our own day, as buildings are sanctified over people. As we speak, “people of faith” seek to elevate themselves and enshrine their interpretation of the Bible into law, limiting reproductive rights and attacking those whose gender and sexuality threaten concrete binary thinking. The religious voice has been usurped but no one is recognizing that they need to offer a sin offering for the nazirites of our own day.

Nasso is a timely invitation to think critically about our faith. Are we carrying a structure that feels like a burden, or are we honoring the fluidity by which G!d dwells within us? The Talmud (Sotah 39a) notes that the priestly blessing that is also contained in this biblical passage must first be recited with the words “who has commanded us to bless WITH LOVE”. This is necessary to specify, because the blessing’s biblical context is one that is actually devoid of Love and compassion.

The biblical text of the blessing further notes that this is about putting G!d’s Name upon the people (Numbers 6:27). How shall we bless one another? We bless when we look at others with love and see G!d. At a time when G!d’s Name has been separated (=gerush) from Love, and G!d’s tabernacle has traveled through the wilderness in such a way that violence is its legacy, it is more urgent than ever for us to reclaim the religious voice. We have to put G!d’s Name upon the people who are being judged and condemned. We must be like the kohanim and affirm the ways that G!d is Present within them: this is the blessing. This is the way we will carry the tabernacle forward: by recognizing the ways that G!d is Present in each of us.

There are many ways that we can join the growing movement of folks who are coming together to reclaim the religious voice. Faith in Action is one organization that seeks to do this by building bridges of connection between diverse identities and religious backgrounds, to focus instead on what unites us. Organizing locally with other faith communities around social justice issues is the way to create the Unity that ensures blessing.

Let us speak out loudly against literal interpretations of the bible or any teaching that calls upon us to separate ourselves from one another and to judge rather than to love. May we be blessed with tenderness and recognize G!d’s Name upon each person that we encounter. May we show our Love for G!d in the ways we respond to the faces of all those that we encounter. May we be blessed with peace, and through us, may our world be blessed with peace.

Rabbi Dr. Nachson Siritsky MSSW, RSW, BCC, works as a social worker and therapist, as well as serving as the rabbi of an emerging Reform Jewish community in Atlantic Canada. A second-generation Holocaust survivor, Rabbi Siritsky’s rabbinate has long been dedicated to “keruv” – an unwavering commitment to advocacy for 2SLGBTQIA+ and interfaith families and the creation of inclusive Jewish communities that are unconditionally welcoming of all spiritual seekers, regardless of their religious background, relationship status, identity, or Hebrew-speaking ability.

Artist Steve Silbert is on the Bayit Board of Directors and is Lead Builder for Bayit Games.