Noah’s Ark: A Failed Ally-Ship

Part of a yearlong series about building and builders inspired by the Torah cycle.

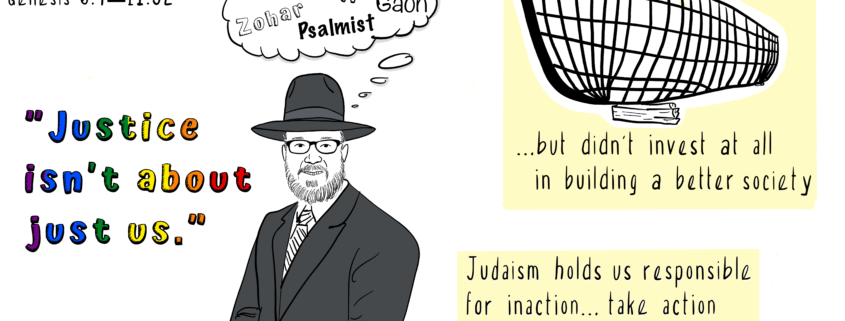

“Justice can never be about just us.” Noah, therefore, certainly wasn’t a just person – and in many ways, failed at being just a person. For 120 years Noah toiled to build an ark of self preservation, but didn’t invest at all in building a better society. He saved himself, his family, and some animals, but didn’t offer a single prayer for the people of his generation. The Zohar writes that because of this, God names it the “Flood of Noah” and sees Noah as if he caused the destruction of the world.

At the beginning of the story (Gen 6:9) Noah is introduced as “a righteous man, perfect in his generations; Noah walked with God”. Before the flood (Gen 7:1) he is no longer perfect, but is still called righteous. After the flood (Gen 7:23) he survives only as Noah, and then defiles even that basic human identity (Gen 9:20). He finds himself alive, but not so different from those whom he let die.

He wasn’t able to see the Godliness in humanity. Not in others, and in the end, not even in himself. With all the effort towards self preservation, he failed to preserve even self.

Rashi interprets “Noah walked with God” as “Noah needed support to bear him up.” God was Noah’s ally and expected him to reciprocate towards God’s creations. Rashi contrasts this with Abraham about whom it is written (Genesis 17:1) “Walk before me.” He writes: “but Abraham would strengthen himself and walk in his righteousness on his own.”

These verses are referenced by the Vilna Gaon (18th century) in his commentary on the first entry of the Code of Jewish Law. The Rema, quoting the Psalmist, opens “I have set the Lord before me constantly” (Psalms 16:8); he then adds “this is a major principle in the Torah and among the virtues of the righteous who walk before God.” The Gaon ends his comments with “and this is the entirety of the virtues of the the righteous!”

The difference between one righteous individual and another is simply the degree by which one sees God in the world around them. In the mundane. In nature. In each other.

Abraham saw it; all of our great ancestors did. They prayed, argued, and negotiated with God to save and protect people. When we see something that isn’t ok we are meant to to something about it. Faith is a call to action and gives us hope that we can be part of the solution.

This November, there will be an anti-trans referendum on the ballot in Massachusetts that would legalize discrimination against trans folks. Some of us may find ourselves comforted with thoughts of how it doesn’t affect us directly – because we don’t live there, or because we are cis-gender, or because we don’t feel like we need those protections. But this kind of thinking makes us no better than Noah and part of the problem.

Judaism holds us responsible for inaction. It is therefore incumbent upon us, as Jews, to take action – to build a better society, to push back against measures that will hurt the people of our generation, and (if we live in Massachusetts) to vote yes on this referendum for the dignity and respect of all people.

We live in really hard times, with no shortage of things to be outraged about, but God forbid it should ever get easier to see the world being destroyed around us. We must pursue justice for all or soon we will be pursued for being just us.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] Noah’s Ark: A Failed Ally-Ship […]

Comments are closed.