Vayikra’s aleph and the offerings drawing us together

Part of an ongoing series that explores Torah through an ethic of social justice and building a world worthy of the Divine.

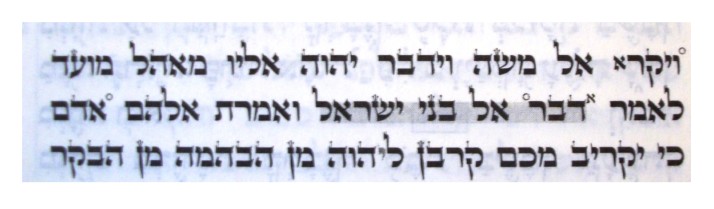

With this week’s parsha, Vayikra (“and He called”) we begin the third book of Torah, Leviticus, also known as the Holiness Code or Priestly Code, as it focuses on the priestly rites in the ancient Jewish Temple. Leviticus details the various sacrificial offerings, korbanot, that individuals would bring to the Temple to atone for sins or mark various occasions. This week also marks the start of the month of Nisan, Chodesh HaAviv, the month of spring (in the northern hemisphere), and, with Passover at mid-month, a period of redemption and freedom. As Jews start the month of Nisan, our Muslim siblings begin Ramadan, the holiest month of their year, marking the revelation of the Quran to the Prophet Muhammad. And mid-month over Passover, our Christian siblings will celebrate Easter with its messages of resurrection, rebirth, renewal and recommitment.

It is an auspicious time with many key messages for an ethic of social justice. This week’s parsha offers an opportunity to connect them all.

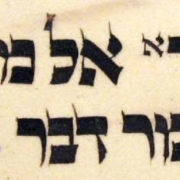

Going back to the parsha, it starts in a somewhat strange way. The first word, vayikra, is written with a small aleph “א“ at the end. And as all biblical parchments contain this small aleph, this isn’t a random typo or scribal error. So why the small aleph?

Medieval commentator Jacob Ben Aher, the Baal HaTurim, posited that the small aleph reflects Moshe’s modesty vis-a-vis God. Moshe, who took down the Torah as recited by God, was going to write vayakar ויקר , that God happened upon Moshe and told him to then give the Israelites a message. However, God wanted the aleph in, showing God’s intention and care in addressing Moshe (changing the meaning from God happened upon Moshe to God called out to Moshe), indicative of God’s love for Moshe. Moshe acquiesced, but kept the aleph small, as a sign of humility or modesty before the Divine:

Kitzur Baal HaTurim on Leviticus 1:1:1: And He called. The א of ויקרא is written as a small letter because Moshe wanted to write ויקר (and it happened), the way it is written regarding Bilaam, which implies God appeared to him only as a chance occurrence. God, however, told him to write the א which indicates His love, but Moshe made it small.

The Hasidic master the Sfat Emet took a somewhat different approach to the small aleph. For the Sfat Emet, the small aleph helps explain why Moshe has to teach parts of Torah to the Israelites from the Tent of Meeting (ohel moed). See, Moshe had received the whole Torah during his 40 day and 40 night sojourn with God at the top of Mount Sinai – this would be the “big” aleph “א“ – expansive, complete, infinite even. Yet the average person couldn’t handle such energy, and so Torah had to be communicated to people in more bite-size pieces reflecting the constricted consciousness of the world we live in – the small aleph. In turn, the Israelites connect back to the deeper source through sacrificial offering, korbanot, which comes from the root “ק־ר־ב” which means “to draw near.” (see Sfat Emet on Vayikra, 1901)

Lord Rabbi Jonathan Sacks z’l built on these teachings. The aleph, he noted, is the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet and also of the Ten Commandments (אָֽנֹכִ֨י יְהֹוָ֣ה “I am YHVH”). It is a letter, indeed, of divinity, opening to all directions, all-encompassing.

Rabbi Sacks taught that perhaps the aleph is small here at the start of vayikra in order to signify that God exists not just in grand events, but in the small gestures that make up our days, the acts of kindness that we show towards one another, when we bring each other coffee to the daily grind of working for a better world, when we listen, learn, grow, love, and ally up for each other.

And connecting back to a key theme of Vayikra/ Leviticus, we can understand these gestures, small and big, as being our offerings / our korbanot, our ways of drawing near to each other and to the Divine.

Indeed, the aleph, as a vowel, is a letter reliant on other letters to make a sound. And by extending out into all directions, the aleph is fundamentally connective. While infinite, the aleph is also totally dependent on other letters to be manifested in time and space. Neither the aleph, nor we, exist in a vacuum. Our tradition doesn’t exist in a vacuum. This holy month of Nisan, of Ramadan, of Easter, when we are called to reflection, liberation, and renewal: how do we manifest our offerings?

During this month that’s holy to three major religious traditions, one way we can reflect on the tiny א is through the humility of remembering that ours isn’t the only sacred calendar. Making space for each others’ holy times is one way we can honour the multiplicity of paths toward what we name as God. For example, learning about each other’s traditions and what they mean for us all, perhaps joining in an iftar meal (and supporting Muslim colleagues who are fasting during the day), working on joint causes (such as combating poverty and discrimination, caring for our environment), asking questions about what this holy time means for each other and listening, deeply.

This month, and always, may we manifest the small, connective, expansive aleph between us, and together may we manifest the Divine.

Rabbi Dara Lithwick, the lead builder at Builders Blog, is an advocate for LGBTQ2+ inclusion. When not at work as a constitutional and parliamentary affairs lawyer, Rabbi Dara chairs the Reform Jewish Community of Canada’s Tikkun Olam Steering Committee and is active at Temple Israel Ottawa, and this winter can be found serving as ski patrol at Sommet Edelweiss. She is a member of Bayit’s Board of Directors.