Mishpatim, the Rule of Law, and the Living Tree

Part of an ongoing series that explores Torah through an ethic of social justice and building a world worthy of the Divine.

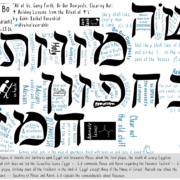

וְאֵ֙לֶּה֙ הַמִּשְׁפָּטִ֔ים אֲשֶׁ֥ר תָּשִׂ֖ים לִפְנֵיהֶֽם׃

These are the rules that you shall set before them (Ex. 21:1)

In last week’s parsha (Yitro), God gave the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai, key principles of the relationship between us and the Divine. This week’s parsha goes into detail, setting out a range of rules to govern how we interact with each other.

The Ten Commandments can be understood as setting out the vision of a just society, the why and what of the covenantal relationship between God and the Israelites. Building on that, this week’s parsha sets out the how, the practical tachlis, of building a society worthy of the Divine. As Mishpatim teaches us, a just world is one built on equality and the rule of law, one that takes particular care of the marginalized amongst us and does not cater to the mighty or powerful. In Mishpatim the Divine is in the details.

The rule of law, or a rules-based legal order, is, at its core, a collection of precepts articulating how we should relate to each other. In today’s understanding of the rule of law, this mode of governance is founded on transparency, accountability, equality, and fairness. As set out by the United Nations:

The ‘rule of law’ … refers to a principle of governance in which all persons, institutions and entities, public and private … are accountable to laws that are publicly promulgated, equally enforced and independently adjudicated, and which are consistent with international human rights norms and standards.

– United Nations Security Council, “The rule of law and transitional justice in conflict and post-conflict societies”, S/2004/616 at para. 6 (see also: What is the Rule of Law – United Nations and the Rule of Law)

The rule of law means that no person is above the law, and that neither popularity nor wealth nor even poverty should have influence in a court of law. See for example Exodus 23: 2-3:

לֹֽא־תִהְיֶ֥ה אַחֲרֵֽי־רַבִּ֖ים לְרָעֹ֑ת וְלֹא־תַעֲנֶ֣ה עַל־רִ֗ב לִנְטֹ֛ת אַחֲרֵ֥י רַבִּ֖ים לְהַטֹּֽת׃

You shall neither side with the mighty to do wrong—you shall not give perverse testimony in a dispute so as to pervert it in favour of the mighty—

וְדָ֕ל לֹ֥א תֶהְדַּ֖ר בְּרִיבֽוֹ׃ {ס}

nor shall you show deference to a poor person in a dispute.

Instead, the rule of law is founded on equity and fairness and honesty, and protects the rights of the marginalized from abuse. For example see Exodus 23:6-9:

לֹ֥א תַטֶּ֛ה מִשְׁפַּ֥ט אֶבְיֹנְךָ֖ בְּרִיבֽוֹ׃

You shall not subvert the rights of your needy in their disputes.

מִדְּבַר־שֶׁ֖קֶר תִּרְחָ֑ק וְנָקִ֤י וְצַדִּיק֙ אַֽל־תַּהֲרֹ֔ג כִּ֥י לֹא־אַצְדִּ֖יק רָשָֽׁע׃

Keep far from a false charge; do not bring death on those who are innocent and in the right, for I will not acquit the wrongdoer.

וְשֹׁ֖חַד לֹ֣א תִקָּ֑ח כִּ֤י הַשֹּׁ֙חַד֙ יְעַוֵּ֣ר פִּקְחִ֔ים וִֽיסַלֵּ֖ף דִּבְרֵ֥י צַדִּיקִֽים׃

Do not take bribes, for bribes blind the clear-sighted and upset the pleas of those who are in the right.

וְגֵ֖ר לֹ֣א תִלְחָ֑ץ וְאַתֶּ֗ם יְדַעְתֶּם֙ אֶת־נֶ֣פֶשׁ הַגֵּ֔ר כִּֽי־גֵרִ֥ים הֱיִיתֶ֖ם בְּאֶ֥רֶץ מִצְרָֽיִם׃

You shall not oppress a stranger, for you know the feelings of the stranger, having yourselves been strangers in the land of Egypt.

That said, the law is not an end in and of itself. In accordance with the rule of law, laws evolve as society evolves, and that is true of Jewish tradition as well. Indeed, throughout Mishpatim we see the bases of all types of law: criminal law, civil law, ethics and religious traditions. While today some of the Torah’s provisions may not make literal sense to us, we nonetheless strive to stay true to the values that underpin its 613 mitzvot.

In Jewish life as well as in secular life, our ability to interpret the law to address contemporary realities keeps the law relevant and helps it continue to guide us. Here in Canada, in the late 1920s five women petitioned the Government of Canada to include women under the definition of “persons” in the British North America Act, the precursor to Canada’s Constitution, in order that they may qualify to serve as Senators. The Famous Five, as we now refer to them, took their case all the way to the highest Court of Appeal at the time, the UK Privy Council.

The day the Privy Council’s decision was rendered was a great day not only for women but for Canadian law. In his judgment, Viscount Sankey coined the phrase that has been an animating premise of our constitutional law ever since. He stated: “The British North America Act planted in Canada a living tree capable of growth and expansion within its natural limits.”

To this day, when Canadians interpret our Constitution, we look at what its words mean in the context of the society in which we live. We try to give life and meaning to the text in the real world. As cautioned by Canadian Supreme Court Chief Justice Dickson more than half a century later in a later case, we should not “read the provisions of the Constitution like a last will and testament, lest it become one” (Hunter v. Southam Inc., [1984] 2 S.C.R. 145 at p. 155). The same is true of how I relate to the Torah.

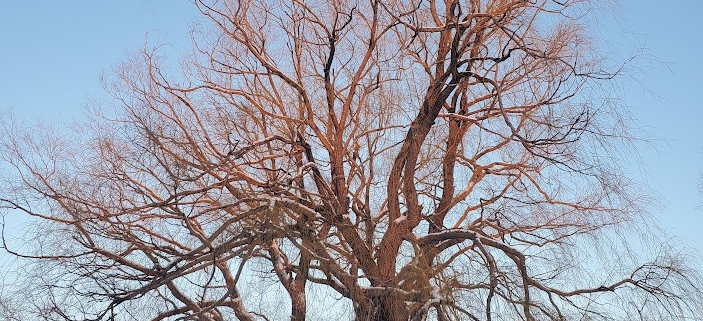

The goal of the BNA Act was to give Canada a constitution, which like all written constitutions, would evolve through its usage and convention. In Mishlei, Proverbs, the Torah is referred to as a an “eitz hayyim”, a “living tree”, giving life to all who grab hold of her (at 3:18 and 3:17, עֵץ־חַיִּ֣ים הִ֭יא לַמַּחֲזִיקִ֣ים בָּ֑הּ וְֽתֹמְכֶ֥יהָ מְאֻשָּֽׁר). As a living tree, Torah is always relevant, rooted in the ground (in the rule of law) and stretching out to the heavens, growing all along

(Of note, Viscount Sankey, who coined the famous phrase, studied first at Lancing College and then at Jesus College at Oxford, both Anglican schools. Perhaps Lord Sankey’s “living tree” approach to the British North America Act was premised on an interpretation of verse 3:18 from Proverbs, Torah as a tree of life for those who hold on to it!)

Understanding our Torah as a living document, a Tree of Life, also necessitates an evolving response to the call to action that we find in Parsha Mishpatim and throughout the biblical texts. Our task is to build a society of ever-greater justice, expansive in our understanding of what’s right while remaining rooted in the values that underpin our written legal texts.

As a living document, the Torah requires us to nurture her and be true to her. In other words, we must sustain the tree in order for it to sustain us. We have to tend to it, water it, even prune our understanding of it, so it can continue to grow and evolve while remaining rooted. As we are taught in this week’s parsha, that’s how we uphold the rule of law and all it stands for – by building a just society governed justly.

Rabbi Dara Lithwick, the lead builder at Builders Blog, is an advocate for LGBTQ2+ inclusion within diverse Jewish spaces and for Jewish inclusion in LGBTQ2+ spaces. When not at work as a constitutional and parliamentary affairs lawyer, Rabbi Dara chairs the Reform Jewish Community of Canada’s Tikkun Olam Steering Committee and is active at Temple Israel Ottawa, and this winter can be found serving as ski patrol at Sommet Edelweiss. She is a member of Bayit’s Board of Directors.