Bereishit: Partnering with God in Co-Creation

Part of an ongoing series that explores Torah through an ethic of social justice and building a world worthy of the Divine.

This week we begin again, a new year, a new Torah cycle, with the ultimate beginning “בְּרֵאשִׁ֖ית בָּרָ֣א אֱלֹהִ֑ים”, Bereishit barah Elohim, often translated as “In the beginning God created” or “when God began to create.”

Nachmanides, the Ramban, wrote that “the Holy One, blessed be He, created all things from absolute non-existence.” How do we create something from nothing? How do we begin?

Sometimes we begin just by, well, beginning – by taking the proverbial plunge into the unknown, and refine from there.

Indeed, the narratives that follow in the five books of Moses take us through creation and also through destruction and despair, failures as well as successes, triumphs and missed opportunities. Life is messy – and creating is a messy process. And Torah also shows human and divine capacity to recalibrate, to reconcile, and to renew.

This year Bayit: Building Jewish will be blogging through the Torah’s 54 parshiyot with a focus on building a world worthy of the Divine- one that honours our earth and each other and all creation. It will be messy, and we’ll be here for it.

The first chapter of Bereishit, of Genesis, sets out how the Divine created night and day, heaven and earth, plants and trees, sun and moon and stars, fish and birds, mammals, and, then, humans. Genesis 1:27 reads “וַיִּבְרָ֨א אֱלֹהִ֤ים ׀ אֶת־הָֽאָדָם֙ בְּצַלְמ֔וֹ בְּצֶ֥לֶם אֱלֹהִ֖ים בָּרָ֣א אֹת֑וֹ זָכָ֥ר וּנְקֵבָ֖ה בָּרָ֥א אֹתָֽם׃ ”, “And God created humankind in the divine image, creating it in the image of God— creating them male and female.”1 A bit later, at Genesis 1:31, God takes in all that God created, and finds it tov me’od – “very good.“

The next chapter of Genesis contains a slightly different account of creation, particularly of humanity. Here, we are products of the earth, imbued with Divine soul-breath: “וַיִּ֩יצֶר֩ יְהֹוָ֨ה אֱלֹהִ֜ים אֶת־הָֽאָדָ֗ם עָפָר֙ מִן־הָ֣אֲדָמָ֔ה וַיִּפַּ֥ח בְּאַפָּ֖יו נִשְׁמַ֣ת חַיִּ֑ים וַֽיְהִ֥י הָֽאָדָ֖ם לְנֶ֥פֶשׁ חַיָּֽה” “God יהוה formed the Human from the soil’s humus, blowing into their nostrils the breath of life: the Human became a living being.” (Genesis 2:7)

Both versions of the creation narrative contain within them a fundamental premise that all people are inherently equal and holy, and that humanity’s existence is inextricably bound in that of the whole of creation. In the first narrative, we are formed alongside the earth and the sky and birds and plants and animals, akin to siblings, though imbued with Divine awareness as being in the Divine image. In the second narrative we are literal progeny of the earth as well as of the Divine.2

The Yalkut Shimoni, a mediaeval midrash on the Torah, posits that the soil used to create the first human came from the earth’s four corners, implying a deep belonging and connection to all soil:

God gathered the dust [of the first human] from the four corners of the world – red, black, white and green. Red is the blood, black is the innards and green for the body. Why from the four corners of the earth? So that if one comes from the east to the west and arrives at the end of his life as he nears departing from the world, it will not be said to him, “This land is not the dust of your body, it’s of mine. Go back to where you were created.” Rather, every place that a person walks, from there she was created and from there she will return.” (source)

The Talmud, in Sanhedrin 37a:13-15, further comments on how the creation of a singular person, Adam, emphasises radical equality and a vision of peace among people:

Therefore the first human being, Adam, was created alone, to teach us that whoever destroys a single life, the Torah considers it as if he destroyed an entire world. And whoever saves a single life, the Torah considers it as if he saved an entire world.

Furthermore, only one person, Adam, was created for the sake of peace among men, so that no one should say to his fellow, ‘My father was greater than yours….

Also, man [was created singly] to show the greatness of the Holy One, Blessed be He, for if a man strikes many coins from one mould, they all resemble one another, but the King of Kings, the Holy One, Blessed be He, made each man in the image of Adam, and yet not one of them resembles his fellow.

However, despite these lofty visions of humanity and creation, the rest of the first parsha of Genesis contains murder and mistreatment, with wickedness spreading throughout humanity. By the end of the parsha God has had enough. The text reads that God “had a sorrowful heart (“ וַיִּתְעַצֵּ֖ב אֶל־לִבּֽוֹ”), and that God יהוה said, “I will blot out from the earth humankind whom I created—humans together with beasts, creeping things, and birds of the sky; for I regret that I made them” (Genesis 6:6-7).

And while we learn in the next parsha that God does not end up destroying all of creation, God does come close with Noah and the flood. God realises that by enabling us to have free will, choice, and responsibility (what may distinguish us from other elements of creation, what may indeed make us “divine”), God is also enabling us to mess up

And this begs the question, as raised by Lord Rabbi Jonathan Sacks z’l,“Why then did God take the risk of creating the one form of life capable of destroying the very order He had made and declared good? Why did God create us?”

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel z’l answered the question boldly: “God’s dream is to be not alone, but to have humanity as a partner in the drama of continuous creation.” As Rabbi Michael Lerner adds (in Jewish Renewal), “By whatever we do, by every act we carry out, we either advance or obstruct the drama of redemption.”

We are both of this world, literally made from the earth, and imbued with divinity, with creative capacity.

Rabbi Sacks cites a passage in the Talmud, in Sanhedrin 38b, :

When the Holy One, blessed be He, came to create man, He created a group of ministering angels and asked them, “Do you agree that we should make man in our image?”

They replied, “Sovereign of the Universe, what will be his deeds?”

God showed them the history of mankind.

The angels replied, “What is man that You are mindful of him?” [Let man not be created].

God destroyed the angels.

He created a second group, and asked them the same question, and they gave the same answer.

God destroyed them.

He created a third group of angels, and they replied, “Sovereign of the Universe, the first and second group of angels told You not to create man, and it did not avail them. You did not listen. What then can we say but this: The universe is Yours. Do with it as You wish.”

And God created man.

But when it came to the generation of the Flood, and then to the generation of those who built the Tower of Babel, the angels said to God, “Were not the first angels right? See how great is the corruption of mankind.”

And God replied (Isaiah 46:4), “Even to old age I will not change, and even to grey hair, I will still be patient.”

God, here, has faith in humanity, has faith in us. Even when things are bad, when we mistreat each other, when we mistreat the earth and its creatures, God believes in our capacity for change. God believes, as is stated later in Torah, in our ability to pursue justice and righteousness (tzedek, tzedek tirdof!), to care for the widow, the orphan and the stranger in our midst, to build a world of lovingkindness (from Psalm 89:3 olam chesed yibaneh).

Imagine a gray-haired, infinitely patient God who does not give up on us, who does not lose faith in us. This God, Rabbi Sacks adds, is one that says “I will wait for as long as it takes for humans to learn not to oppress, enslave or use violence against other humans.” Sacks concludes that this is the essence of why we were created, our messy and fallible selves: “God has patience. God has forgiveness. God has compassion. God has love.”

As we begin a new year and a new cycle of Torah, do we still have faith in God, and in God’s faith in us? With everything going on, with the challenges and destruction that we see in our world today, do we have the strength to double down on compassion and love to co-create and build a more just world? Let us begin together, with intention, with beginning.

Rabbi Dara Lithwick, the lead builder at Builders Blog, is an advocate for LGBTQ2+ inclusion within diverse Jewish spaces and for Jewish inclusion in LGBTQ2+ spaces. When not at work as a constitutional and parliamentary affairs lawyer, Rabbi Dara chairs the Reform Jewish Community of Canada’s Tikkun Olam Steering Committee and is active at Temple Israel Ottawa. She is a member of Bayit’s Board of Directors.

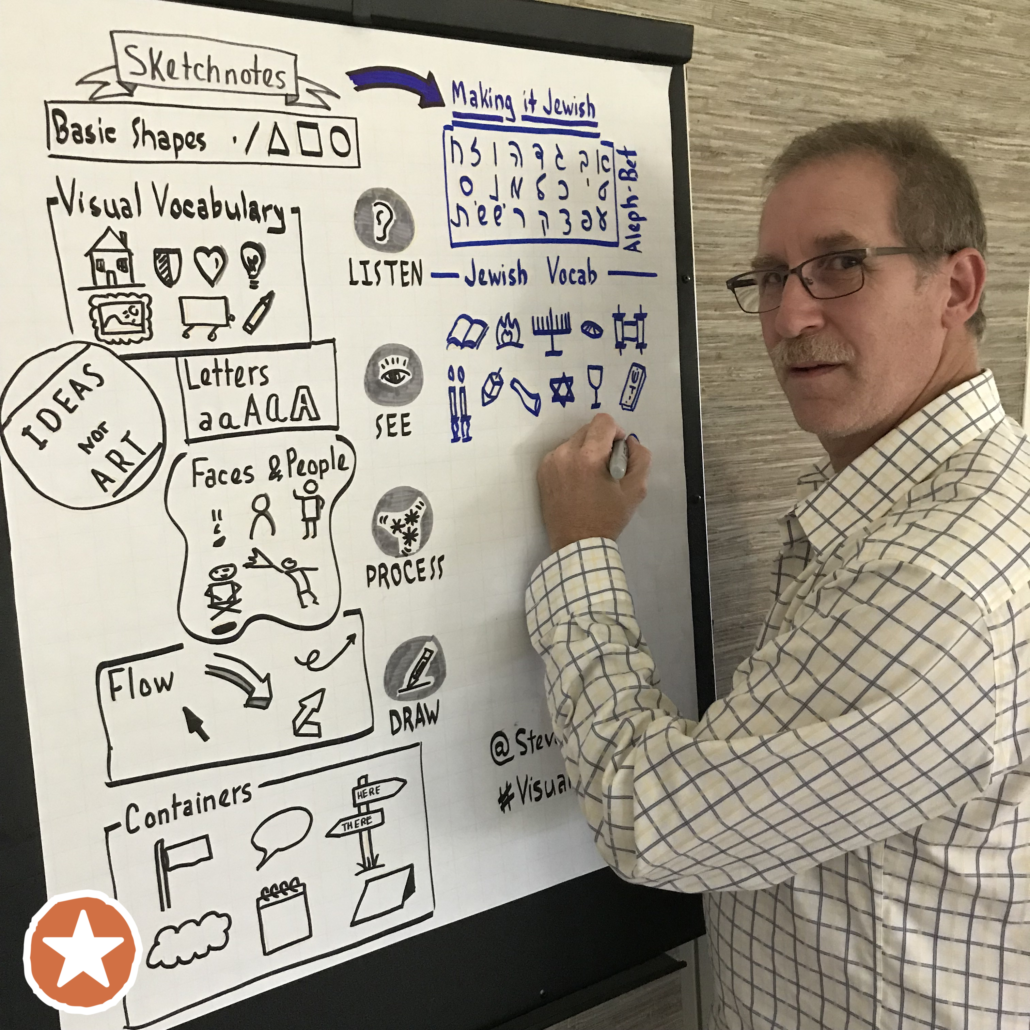

Steve Silbert, illustrator for this post, is also a member of Bayit’s Board of Directors. He is also part of Bayit’s Liturgical Arts Working Group, and the lead builder at Bayit Games. Steve uses sketchnotes as an Agile Coach, where he teaches visual facilitation basics in software development and marketing.

1. [I, and others, read this as a merism so it means not only “male” and “female”, but the whole spectrum of gender beyond and between. Another example of a merism is “I searched high and low”, which is akin to saying “I searched everywhere”, i.e. not just high and low but everything in between.]↩

2. Thank you to Dan Abramson for our chats about this at URJ Camp George summer 2022.↩