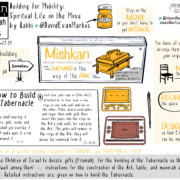

People of the Building Fund: Four Paths Through the “Edifice Complex”

Part of a yearlong Torah series about building and builders in Jewish spiritual life.

“Don’t give to the Building Fund,” said no synagogue leader ever.

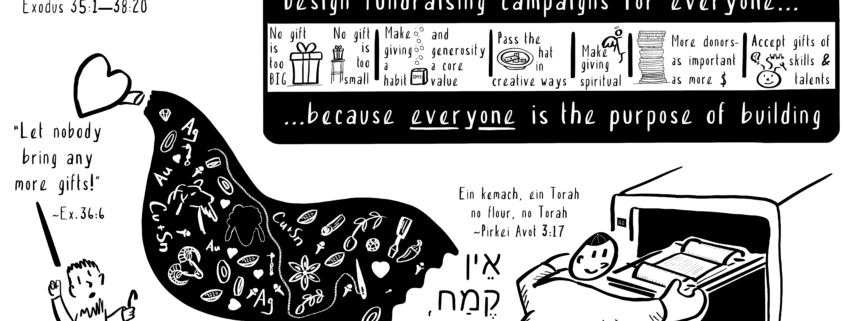

Most community leaders would love to have Moses’ problem in “fundraising” for the Mishkan. Moses received so many resources from “everyone” to build Mishkan that he had to stop them from giving: “Let nobody bring any more gifts!” (Exodus 36:6).

Most community leaders would love to have Moses’ problem in “fundraising” for the Mishkan. Moses received so many resources from “everyone” to build Mishkan that he had to stop them from giving: “Let nobody bring any more gifts!” (Exodus 36:6).

Since then, Jewish spiritual life has felt nostalgic for the Mishkan’s universal generosity and collective plenty. Judaism isn’t alone: all spiritual communities must keep one eye on funding for needful realities, but who likes to talk about it? How many in spiritual life are left distracted, exhausted or dispirited by talk of money?

When does fundraising support wise spiritual building, and when does fundraising become a hamster wheel that spins away from spirituality? For all who care about wisely building the Jewish future, that’s a key question of Parshat Vayakhel.

Jewish spirituality is blunt about resourcing spiritual community: Ein kemach, ein Torah (“no flour, no Torah”) (Avot 3:17). The catch is raising “dough” for buildings that become a “structural fetish” rather than a sacred way to sense the sacred.

Bayit builder Ben Newman reminds us that God applauded Moses for shattering the tablets at the Golden Calf, teaching that no “things” are inherently holy – not even the tablets of the Ten Commandments – except as they inspire real spiritual experience. When resource drives elevate things over people, those things must break to teach us what’s truly holy and what’s just the latest Golden Calf that we began to worship.

When we build in ways that rely on major donors, less affluent others can get wrong ideas that weaken spiritual community. They can learn that their gifts are less valued. They can learn to outsource generosity to others. Some even learn to take community for granted. When we don’t feel a strong stake in community, community itself withers.

Thank goodness for angel donors who do a world of good in a world that needs all the good they can do. Thank goodness for vibrant Jewish spaces that nourish the Jewish future. Still, we must ask how we keep forgetting that everyone gave to the Mishkan? What happened to a generosity culture so universal that Moses had to say, “No more!”?

We must learn the Mishkan’s lesson about democratizing generosity. We must reorient Jewish spiritual building to the goal of cultivating a truly universal culture of giving.

This goal asks a different spiritual design than any “edifice complex” whose goal is a thing that relies on angel donors and projects “too big to fail.” Reorienting spiritual design asks for fundraising in ways that put people and spiritual experience above all.

Four Ideas to Build a Trust-Based Generosity Culture

Here are four ideas to build a more universal generosity culture while raising the dough. All four ideas entail risk because they ask substantial trust – but trust is paramount to build a relational and spiritual Judaism in which everyone feels that they fully count.

Here are four ideas to build a more universal generosity culture while raising the dough. All four ideas entail risk because they ask substantial trust – but trust is paramount to build a relational and spiritual Judaism in which everyone feels that they fully count.

Teach universal giving as a core community value – and be explicit about it. Effective fundraisers know that tzedakah is a spiritual act that joins learning and prayer as Judaism’s three pillars (Avot 1:2). If we wouldn’t accept a Jewish life that raises even unintended barriers to learning or prayer, then we mustn’t accept an “edifice complex” that even inadvertently signals that anyone or their gifts are second rate. Teach and model the Jewish keystone principle that everyone gives and everyone gets, because that’s what binds and uplifts a truly vibrant community.

Segment fundraising campaigns so that success depends on both angel donors and “everyone.” Court major donors for key initiatives, but deliberately leave out something vital (like doors or programs) for the whole community to fund – and be explicit about it. Without those essentials for the community to fund, a major “edifice complex” would be incomplete, an empty shell or a boondoggle – and that’s the right message to send so that “everyone” has a stake in success.

Learn from our Christian cousins and “pass the plate” in Jewish ways. For communities uncomfortable handling money on Shabbat, try a pre-Shabbat online ritual, a #BeALight Havdalah giving ritual, or a Shabbat pledge card. For others, literally “pass the plate,” or spiritually uplift the tzedakah box. Teach so it feels spiritual rather than “pay to pray”: after all, Maimonides taught about giving before being asked. Torah was read on market days (when people handled money), so maybe we pass the tamchui (charity plate) when we honor Torah. Try alternatives, but send a clear message that universal generosity is as vital to Jewish communal life as Torah.

Make sure that giving isn’t only about money. Even when Moses stopped donations for the Mishkan, both time and talent were welcome. People less affluent in funds might be wealthy in time and talent. Solicit their gifts with the same honor as cash – not as a substitute for cash but as a complement. Plan for these gifts: pass the plate for them and make wise use of them. After all, aren’t these gifts of hands-on community among the reasons for spiritual building in the first place?

Conclusion

All four ideas – teaching universal participation, segmented donor campaigns, passing the plate, and soliciting non-cash gifts – entail risk. They ask trust in alternatives to the seeming certainty of big checks. This kind of trust can seem especially fanciful when plans and campaigns are “too big to fail.”

Spiritually speaking, this kind of trust is the point. People are the point. Making room for others is the point. If leaders don’t leave space for others to fill, and show everyone how important and needed everyone is, then others are sure not to step forward. Isn’t that exactly today’s problem in Jewish community life?

The Mishkan solicited everyone’s gifts, because “everyone” was the purpose of building. At long last, we in Jewish life today must do the same.

By Rabbi David Markus. Sketch Note by Steven Silbert