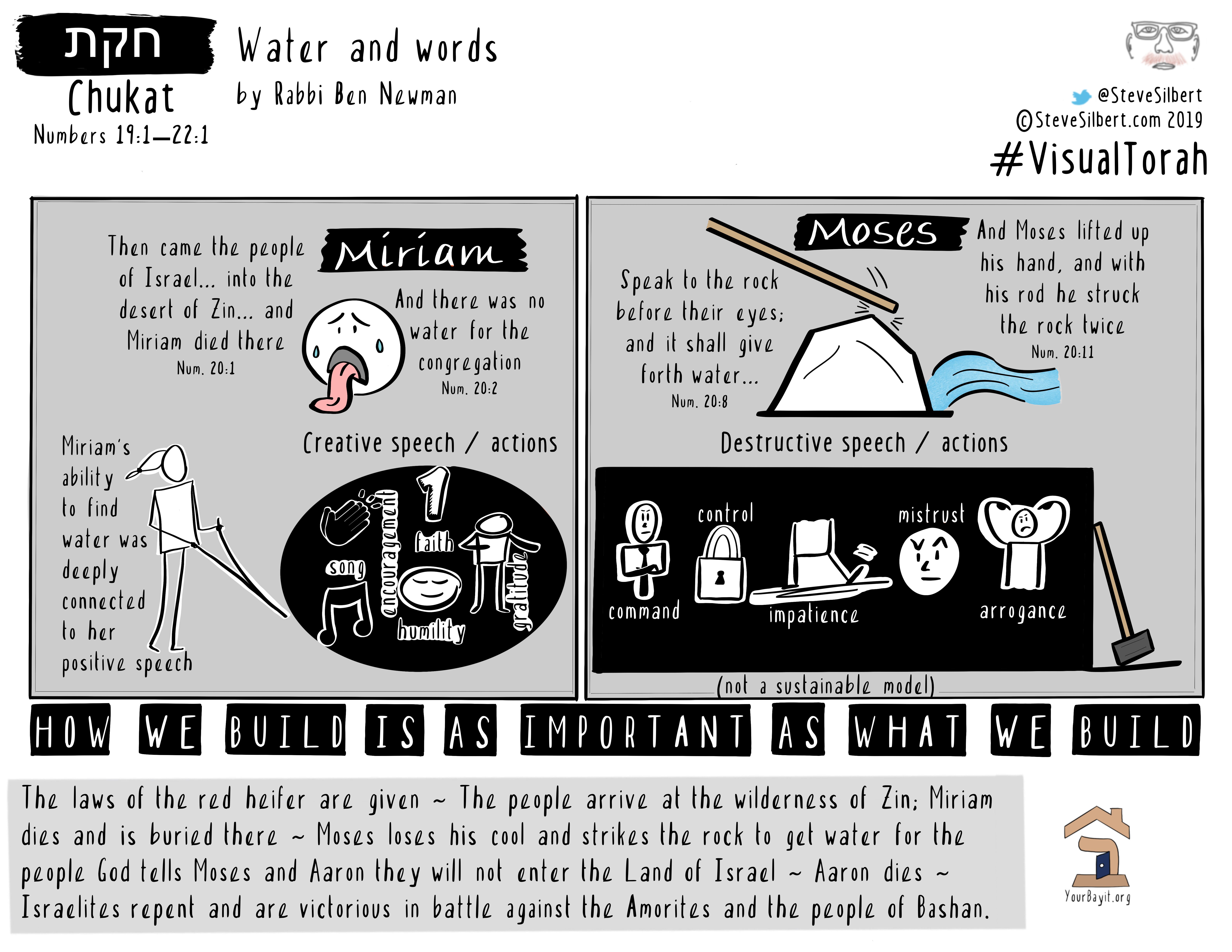

Water and Words

Part of a yearlong Torah series on spiritual building and builders in Jewish life.

Words have power. They have the power to create, and the power to destroy. Think of any human creation, from the Brooklyn Bridge to Harry Potter World: they were all created through words. On the other side of the coin, think of any human act of destruction, from World War II to the devastating effects of microplastics on the environment, all put into effect through words.

Language is arguably the most powerful tool that humans possess. It is no coincidence that we call the process of creating magic a “spell”– literally from the word “to spell.” In Parshat Chukat we see an incident that seems somewhat inexplicable unless we take into account the awesome power of our words.

In Numbers 20 we read of the death of Miriam, the sister of Moses. More than just the sister of Moses, Miriam was a leader in her own right. One of her most important functions was to find the water in the Wilderness. In the Wilderness, finding water was literally a life or death matter. So it is not surprising that right after Miriam dies, and there is no one to find water, the people begin to complain:

“The community was without water, and they joined against Moses and Aaron.The people quarreled with Moses, saying, ‘If only we had perished when our brothers perished at the instance of the LORD!’”

Moses goes to G!d who tells him ““You and your brother Aaron take the rod and assemble the community, and before their very eyes speak to the rock and tell it to yield its water.” (Numbers 20:8) However, Moses’ anger gets the better of him, and instead of speaking to the rock, he hits the rock with his staff and says to the people: “Listen, you rebels, shall we get water for you out of this rock?” The water comes from the rock, but G!d’s response to Moses is that because he hit the rock rather than speaking to it, and because “you did not trust Me enough to affirm My sanctity in the sight of the Israelite people,” Moses is prohibited from entering the land of Israel and seeing the fulfillment of his life’s journey. In fact, according to the medieval commentator Rashi, “Scripture discloses the fact that but for this sin alone, they would have entered the land of Canaan.”

What was so wrong with what Moses did? Was it such a horrible sin that he should deserve such an extreme punishment? For me, this divine punishment of Moses reflects Chukat’s core message for us as builders: words have power to create or destroy. Therefore we must choose our words carefully. By hitting the rock rather than speaking to it, and by speaking out of anger to the Israelites calling them rebels, Moses was engaged in destructive rather than creative speech.

In stark contrast, according to Midrash Rabbah, Miriam’s ability to find water was deeply connected to her positive speech. The Midrash connects Miriam’s special relationship with water to Miriam’s leading the women in a song of gratitude after the Splitting of the Sea. Because she expressed gratitude through song for a miracle that occurred through water, she was rewarded with water (Bamidbar Rabbah 1:2). In addition, the Midrash says that the well of water came out of a rock that would follow the Israelites through the desert, and that when people wanted the water to come out of the rock, they would come and stand by it, saying: “Rise up, O well,” and it would rise. According to the Midrash, this was the same rock that Moses struck.

The method of Moses and that of Miriam to draw water from the rock represent two opposite ways of building and leading. We can speak with anger and authority and command as Moses did, or we can sing with gratitude and encouragement as Miriam did. What Chukat tells us is that both methods may produce “water,” but Moses’ method is not sustainable in the long term. The ends may seem to justify the means, but in truth, in the process of building, the ends are the means. As science fiction author Ursula K. Le Guin wrote: “The end justifies the means. But what if there never is an end? All we have is means.” In building the Jewish future, how we build is as important as what we build. No Jewish leader worth their salt should use hurtful or wrongful speech. Better to emulate Miriam who built gratitude with her song.

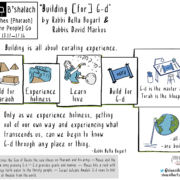

By Rabbi Ben Newman. Sketchnote by Steve Silbert.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] I get water for you from this rock?” and then hitting the rock instead of speaking to it sweetly. His harsh words drew forth water, but not in a sustainable way. Wise community leadership requires a spiritual practice of […]

[…] D’var Torah by Rabbi Ben Newman; sketchnote by Steve Silbert. Read it here: Water and Words […]

Comments are closed.