Responsibility as Redemption / Graceful Masculinity: Vayigash

Part of a year-long Torah series on graceful masculinity and Jewish values.

וְלֹא-יָכֹל יוֹסֵף לְהִתְאַפֵּק, לְכֹל הַנִּצָּבִים עָלָיו, וַיִּקְרָא, הוֹצִיאוּ כָל-אִישׁ מֵעָלָי; וְלֹא-עָמַד אִישׁ אִתּוֹ, בְּהִתְוַדַּע יוֹסֵף אֶל-אֶחָיו.

Joseph could no longer control himself before all his attendants, and he cried out, “Have everyone withdraw from me!” So there was no one else about when Joseph made himself known to his brothers. (Genesis 45:1)

One of the most dramatic moments in the Genesis narrative is when Joseph reveals himself to his brothers, declaring “I am Joseph. Is my father still alive?” The medrash explains that it was Judah who brought Joseph to a point where he could hold back no longer and therefore divulges his true identity. Rabbi Chiya bar Abba posits that Judah’s speech, although directed at Joseph, is actually constructed to appease Joseph, Benjamin, and the other brothers.

We understand why Judah needs to apologize to Joseph and Benjamin. It was Judah’s plan to sell Joseph as a slave, upending Joseph’s life and robbing Benjamin of his only brother from the same mother. But I find it interesting that Rabbi Chiyah also thinks that Judah is appeasing his other brothers as well. The other brothers had wanted to kill Joseph, while Judah suggested they could make some money by selling Joseph as a slave. Judah could argue that his other brothers are equally complicit in what was done to Joseph, but instead he chooses to take full responsibility for the situation.

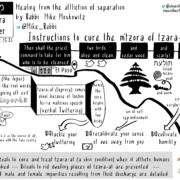

In a relationship, it is an act of grace to take responsibility for our actions and inactions without trying to share the blame. Our choices are meaningful because they represent our will, and as a result they are ours to own. We should make it a daily practice to take stock of our deeds, but Yom Kippur is especially designated as a particular Day of Reckoning in the Jewish calendar. The High Priest in the Yom Kippur Temple service takes full responsibility for the deeds of Israel. He is compared on this day to a graceful groom, reflecting the magnanimous nature of his behavior and the joy of the experience.

The Midrash says that the meal which precipitated Joseph’s revelation happened on Shabbos. Shabbos is a time when we are able to access and orient ourselves to the truth of being G-d’s creations. The Hebrew word for face, פנים, is the same as a word for “inside” because the face gives expression to what is going on internally within a person. Our rabbis teach that the light that emanates from a person’s face is different on Shabbos than during the week and has its source in the holiness of the Garden of Eden. Even Adam, after the sin, didn’t lose that light until Saturday night. Shabbos invites us to remember and take action, to return to the ideal and work to fix the things we broke.

The brothers are rendered speechless by Joseph’s revelation. The medresh uses this as a model for us and our own day of reckoning: “Woe to us on the day of judgment, woe to us on the day of rebuke.” If the brothers were not able to answer Joseph, how are we going to be able to answer G-d?

Joseph has not rebuked his brothers. He has simply revealed the truth of the situation. Chein (grace) can be understood as an acronym for chochma nistera, hidden wisdom. The brothers had originally thought that Joseph was extraneous and expendable. The “judgment” came with Joseph simply letting them know that they had gotten it wrong.

On the Day of Judgement we will all be confronted by the truth of our potential. The prospect of this is terrifying. When people become aware of their failings, they can feel embarrassed and even give up hope of correcting bad behavior. Chein is the ability to see the greatness of the hidden and bring it out. The groom, on the verge of marriage, epitomizes embracing one’s potential and turning it into reality. It is that commitment to the ideal that empowers the groom to take responsibility for inevitable bumps along the way. Acknowledging our mistakes allows us to make amends for the past and better positions us for a more perfect future.

Discussion questions:

What are the consequences of minimizing our own potential for change?

How can one break the cycle of bad habits?

What are some best practices in saying “I’m sorry”?

It isn’t easy to admit that one was wrong. How can those receiving an apology best support a healthy outcome?

By Rabbi Mike Moskowitz. See other #MenschUp posts here.