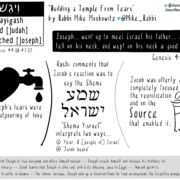

Vayigash: Risking Everything

Part of an ongoing series that explores Torah through an ethic of social justice and building a world worthy of the Divine.

At its base, VaYigash is the parsha in which Joseph reveals himself to his brothers, ultimately reuniting Jacob’s family. The opening lines of the parsha are:

וַיִּגַּ֨שׁ אֵלָ֜יו יְהוּדָ֗ה וַיֹּ֘אמֶר֮ בִּ֣י אֲדֹנִי֒ יְדַבֶּר־נָ֨א עַבְדְּךָ֤ דָבָר֙ בְּאזְנֵ֣י אֲדֹנִ֔י וְאַל־יִ֥חַר אַפְּךָ֖ בְּעַבְדֶּ֑ךָ כִּ֥י כָמ֖וֹךָ כְּפַרְעֹֽה׃

Then Judah went up to him and said, “Please, my lord, let your servant appeal to my lord, and do not be impatient with your servant, you who are the equal of Pharaoh.

Judah’s words open the parsha, and the majority of commentaries open with his statement, and then spend tremendous energy attempting to figure out how his approach to Joseph is going to work (or not) as he asks first for his ear.

Josh Feigelson points out that Rashi’s comment on the parsha’s opening line provides us with an opening to explore the larger question with which we frame this week’s study: “How do we connect?” Rashi explains Judah’s opening words, “Please, my lord, let your servant appeal to my lord” (Gen 44:18) by means of a more literal translation of the Hebrew “May my words penetrate into your ears.”

Otherwise, the majority of the commentaries tend to work like this one from The Netivot Shalom (citing Genesis Rabbah 93:6 to establish that “vayigash” signifies approaching as in prayer: […] The Toldot Yaakov Yosef teaches that our sole interest in prayer is to be able to approach God […] to pour out our hearts, to converse directly with God.

As you can see, these commentaries, as represented by The Netivot Shalom, have absolutely nothing to do with Judah himself, except to infer that his approach to Joseph should be like one ought to approach God: praise first, ask for a favor second.

Judah is the one they all talk about taking the risk in reaching out to Joseph. How careful he had to be to placate Joseph, who Judah perceives as the one with the power. Judah is, in essence, humiliating himself before Joseph. Until at a certain point, Joseph can’t stand it any longer, and clears the room in order to risk everything to tell Judah who he is. Let’s remember, however, what Joseph has overcome in order to reach his position in Egypt.

As Rabbi Yitz Greenberg reminds us (Hadar: VaYigash 5782): the first thing our parsha does is “recount the crime that shattered Jacob’s family.

[…]

The coverup of the crime locks the family into a prison of silence, guilt, and alienation from each other, as they watch their father’s endless grief and self-recrimination.

[…]

In only one way is Joseph damaged: he rejects his family and walls off his past.“

In this context, what does Judah risk? Judah has no control over any of the possible outcomes, and therefore no potential consequences: he’ll get fed or he won’t; Benjamin will come home with him or not; Jacob will die bereft or he won’t..

Joseph is the one who comes out, risking his relationship with his entire family, who have rejected him already. He can’t know what will happen until he takes that chance.

Here’s one coming out story where she gets to keep her family:

She’s crying her eyes out about the end of a relationship, sitting in the passenger seat of her father’s car (a baby blue Ford Galaxy 500!), heading down Interstate 80 at 75 or 80 miles an hour. She tells her father that her break up was with a woman.

There was no car crash.

There was no slamming of brakes.

There was no gasp.

What was there? A quiet voice saying “Oh, thank God, now we can talk about it.”

Here’s another coming out story where things don’t go so well:

She’s sitting in a restaurant, waiting for her mother. They have a rough relationship, she and her mom, but they try. Boy, do they try. Lunch comes, they eat, they chat, and the daughter comes out.

There was no table crashing.

There was no screaming and yelling.

There was no humiliating scene.

They finished lunch, and went their separate ways. There were a few late-night phone calls where she tried to fix her daughter. And then, through the grapevine, she hears that her mom is speaking with the rabbi, and that she’s considering saying Kaddish for her daughter.

Rabbi Dr Erin Lieb Smokler suggests that the Sfat Emet’s comments vis a vis Joseph’s behavior in VaYigash can be understood as: “Joseph was a man who knew how to live on two planes simultaneously. Decades-long separation from his family schooled him in bifurcated living: how to be both attached and independent, rooted and unrooted, spiritual and physical, Jewish and Egyptian. All of that time hiding his identity helped him cultivate a multiplicity of identities and an ability to juggle them.”

Joseph, therefore, unlike Judah, is risking everything: he reveals his true self, puts himself and his current life on the line. Because Joseph cannot stand watching Judah humiliate himself (remember, even Tamar didn’t humiliate Judah!) he clears the room and outs himself: as the boy Judah sold into slavery, as the “fagele” his brothers couldn’t stand, as the favorite of a father who was forced to believe him dead. Joseph reveals himself AS himself, to the very person who changed his life by forcing him into slavery. Joseph risks his job, his life, his position with Pharaoh, and his position with any family he’s made for himself at a time when he can’t know if the family he’s revealing himself to will once again banish him from their lives because of who he is. But he can’t help but hope that he’ll get to keep everything, that he’ll get his family back by letting them know who he is.

Joseph may send his servants out of the room for his conversation with his brother Judah, but what he hopes for is to make a connection with his family, a connection that he views and hopes for as a reward for risking revealing himself to those he cares about

In this past week’s New York Times, columnist Charles M Blow writes:

This Christmas I introduced my boyfriend to my family. It was one of the greatest gifts I ever gave myself. It was the gift of demanding to be seen by the people whom I love in the fullness of myself. It was the gift of forcing my worlds into collision and therefore into singularity. It was the gift of living in truth and walking in freedom.

Does Joseph get this ending? Does Jacob? Can we? Coming out as all of ourselves can be the greatest risk any of us ever take. “Achieving understanding can often feel as hard as trying to penetrate the skull of another.” said George Bernard Shaw. Yet that understanding can lead to the reunification of the most bifurcated family.

Rabbi Cyn Hoffman is a member of the Bayit Board and a Builder in Bayit Publishing.