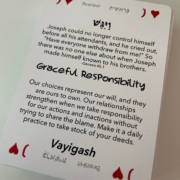

The Other Half of the Battle / Graceful Masculinity: Toldot

Part of a year-long Torah series on graceful masculinity and Jewish values.

וְיַעֲקֹב נָתַן לְעֵשָׂו, לֶחֶם וּנְזִיד עֲדָשִׁים, וַיֹּאכַל וַיֵּשְׁתְּ, וַיָּקָם וַיֵּלַךְ; וַיִּבֶז עֵשָׂו, אֶת-הַבְּכֹרָה.

Jacob then gave Esav bread and lentil stew; he ate and drank, and he rose and went away. So Esav spurned the birthright. (Genesis 25:34)

Sometimes we just forget things. Often though, it’s not that we have actually forgotten, but rather that the clarity of our knowledge is not sufficient to orchestrate our actions.1 If a person stays up most of the night playing video games, it’s not because he forgot that he has to wake up in the morning for work. Rather, just knowing that his alarm will ring soon is not sufficient to change his behavior.

When we say that remembering is a call to action, it is because we want to bring to the fore the knowledge that will cause us to behave appropriately. This requires an awareness of what we have “forgotten,” so that we can counter the memory lapse and orient ourselves towards proper activity.

In our tradition, Esav (Esau) had vast knowledge but there was a disconnect between what he knew and what he did; he was not a talmid chacham, a practitioner of wisdom. He would ask his father detailed questions about halacha, Jewish law, but he did not use that knowledge to influence his actions. Most egregiously, he was not self-aware enough to realize the tremendous gap between his education and his behavior. He thought he was already there and had nothing left to learn; the Hebrew words “Esav” and “complete” have the same numerical value.2 He was completely unaware of how underdeveloped he really was. Our rabbis teach that this was the source of his evil and like an undiagnosed illness, it never got treated.3

It is for this reason that Esav thought that he was fitting to receive the blessings from his father. He didn’t see himself as a sinner, and even the shock of the rejection didn’t arouse any introspection or change. Esav was “in his head,” not connected to the rest of his body, or the rest of the world.4 Tradition teaches that Esav’s head is buried apart from his body, perhaps as a further expression of this disconnect.

It is for this reason that Esav thought that he was fitting to receive the blessings from his father. He didn’t see himself as a sinner, and even the shock of the rejection didn’t arouse any introspection or change. Esav was “in his head,” not connected to the rest of his body, or the rest of the world.4 Tradition teaches that Esav’s head is buried apart from his body, perhaps as a further expression of this disconnect.

Jacob, by contrast, was constantly struggling, evolving, and throwing himself back into the fight for greater awareness. He was born at his brother’s heel, thereby earning himself the name Jacob / Ya’akov (connected to the Hebrew word for heel, עקב / ekev). Jacob consistently fights his way up until G-d grants him a new name, ישראל / Israel, which is an anagram of לי ראש / li rosh, “you are to Me a head.” With this name change,G-d gives Jacob confirmation of his holy transformation.

The space between intentions and impact can be vast and even violent. How can men be expected to know what we don’t know? Judaism teaches that knowing that we don’t know is both a high level of knowledge and also a prerequisite for gaining greater wisdom.

Acquiring this type of sensitivity is truly a gift that comes from the sensing of its absence. When we know that we are not there yet, that there is still much work to be done, then we can be open and worthy of receiving what we need to know.

We thank God for being our source of knowledge in the blessing “You graciously endow man with wisdom,” found in daily prayer. Wisdom is given with grace, and so being wise is not just about knowing facts, but knowing how to be with other people in a way that is graceful. This involves an awareness of how our actions resonate with others.

The Vilna Gaon comments on the verse (Proverbs 3:4) “You will find favor and goodly wisdom in the eyes of G-d and man” that “חן ”, “favor” comes from the language of “חנם” free. It is for that reason, he posits, that “grace” is most commonly paired with the verb “find”.

We can’t rely on our subjective understanding of what’s appropriate based on how we intend an action in our heads. Instead we need to check in and hear from those being affected by what we do. Esav spurned his birthright by minimizing the consequences of his actions. In the mystical tradition, his ministering angel governs though the power of forgetting. When we recognize that wisdom comes from beyond us, that should humble us, and encourage us to take responsibility to internalize wisdom, commit to its application, and regularly review the space between the ideal and our lived, embodied experiences.

Discussion questions:

What framework would enable us to ensure that our actions are having the desired effect?

How can we strengthen the knowledge we have to subdue undesirable habits?

What responsibility comes with being privileged in society?

How does Jacob model a more positive masculinity?

How can we cultivate greater self awareness?

1. עיין מתנת חלקו מ”י ד”ג “השכחה אינו שולטת על הידיע, אלא על מה שהידיעה צריכה לגרום למעשה.↩

2. עשו = 376, שלום = 376↩

3. עיין נאות דשא אות ג↩

4. עיין משנת רבי אהרן ↩

By Rabbi Mike Moskowitz. Image source: Charlene Winfred.