Vayeitzei – Rest, Divine Presence, and Holy Energy

Part of an ongoing series that explores Torah through an ethic of social justice and building a world worthy of the Divine.

“וַיֵּצֵ֥א יַעֲקֹ֖ב” So begins this week’s parsha, with Jacob in motion, having fled from home after receiving his brother Esau’s birthright, on orders to go to his uncle Laban’s in Haran to find a wife and let his brother’s fury subside.

He is on a mission, but as night falls he must pause his journey. The Torah tells us that Jacob “וַיִּפְגַּ֨ע בַּמָּק֜וֹם וַיָּ֤לֶן שָׁם֙”, literally “encountered in (or happened upon) that place and rested there” (Genesis 28:11), begging the question of what place, and what sort of encounter.

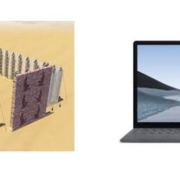

Jacob takes a stone as a pillow and lies down. He falls asleep and begins to dream: he sees a ladder with its base on the ground and its head in the sky with angels or messengers of God ascending and descending the ladder. But not just that. In the dream God is also standing next to Jacob, and tells Jacob that the covenant of his parents and grandparents will extend through him, that his descendants will be numerous and blessed, and that God will protect Jacob and help him return home.

(What a dream!)

Jacob wakes up, exclaiming wow, God is surely in this place “בַּמָּק֖וֹם הַזֶּ֑ה” and I didn’t know it. How awe-some this place is, a home of God’s, a gateway to heaven!

I have always been struck by this story, by the ladder and the messengers and repeated emphasis of the word “מָּק֜וֹם”, makom, place, throughout. Of note, later rabbis came to use Ha-Makom as a name of God, which makes sense here as Jacob had an encounter with God.

This story, for me, contains three key takeaways for an ethic of social justice:

First, the parable highlights the importance of stopping, resting, and taking stock. Many social justice activists, clergy, and educators that I know rarely are able to stop given the magnitude of the issues they deal with, from climate change to poverty and hunger, from gender based violence to systemic racism, from housing and homelessness to the refugee crisis. Yet as our tradition teaches us with the centrality of Shabbat, rest is essential to being able to rejuvenate one’s self, to renew one’s self, and to recenter one’s self, and thus be able to build a better world. And as this parsha demonstrates, only by actually stopping and resting was Jacob able to have his dream and perceive God’s presence, Ha Makom ba makom (the Holy Presence in the place).

Second, God is here, right here, right now, in the shmutz and in the trenches. Jacob encounters God in a liminal space, in the wilderness between Be’er Sheba and Haran, at night, while resting on a rock for a pillow after fleeing home. God is with us here in our messy world with all of its challenges, on the ground, literally present, HaMakom. Our challenge, perhaps, is to notice. The Psalmist wrote Shviti Adonai l’negdi tamid – “I will keep God before me always” (Psalm 16:8). When we struggle, God is there. When we make signs, God is there. When we take part in letter writing campaigns or rallies, God is there. When we gather volunteers and allies, God is there. When we lose focus and snap back to it, God is there. When we cry in despair and defeat and then pick ourselves up again as dinner has to be made, God is there. And knowing that can infuse holiness and meaning to what we do and what we are going through.

Second, God is here, right here, right now, in the shmutz and in the trenches. Jacob encounters God in a liminal space, in the wilderness between Be’er Sheba and Haran, at night, while resting on a rock for a pillow after fleeing home. God is with us here in our messy world with all of its challenges, on the ground, literally present, HaMakom. Our challenge, perhaps, is to notice. The Psalmist wrote Shviti Adonai l’negdi tamid – “I will keep God before me always” (Psalm 16:8). When we struggle, God is there. When we make signs, God is there. When we take part in letter writing campaigns or rallies, God is there. When we gather volunteers and allies, God is there. When we lose focus and snap back to it, God is there. When we cry in despair and defeat and then pick ourselves up again as dinner has to be made, God is there. And knowing that can infuse holiness and meaning to what we do and what we are going through.

Finally, in Jacob’s dream of the ladder, why are the angels/messengers ascending and then descending? Wouldn’t they start in heaven and descend down to earth? The 13th century sage Rabbi Hezekiah ben Manoah (in his compilation the Chizkuni) had the same question. He posited that this led Jacob to understand that the ground, the earth, where Jacob was sleeping was to be God’s home on earth, and so they shepherded between the ground and the heavens to connect and share with the other angels in the heavens. For me the image of the messengers first ascending before descending demonstrates an energy feedback loop, where via our actions and prayers or maybe even our requests for help and partnership, we send holy energy, or shefa up, and holy responsive energy returns back to our world, in a symbiotic exchange (like how how the animal and plant worlds exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide). The work that we do here on our world impacts the heavens, and that changes us in return, ideally through co-creation and healing. What we do, however small or big, matters.

As we head into this Shabbat, may we be able to enjoy some rest to be able to discern Divine Presence and be renewed to continue to heal our world.

Rabbi Dara Lithwick, the lead builder at Builders Blog, is an advocate for LGBTQ2+ inclusion within diverse Jewish spaces and for Jewish inclusion in LGBTQ2+ spaces. When not at work as a constitutional and parliamentary affairs lawyer, Rabbi Dara chairs the Reform Jewish Community of Canada’s Tikkun Olam Steering Committee and is active at Temple Israel Ottawa. She is a member of Bayit’s Board of Directors.

Steve Silbert, illustrator for this post, is also a member of Bayit’s Board of Directors. He is also part of Bayit’s Liturgical Arts Working Group, and the lead builder at Bayit Games. Steve uses sketchnotes as an Agile Coach, where he teaches visual facilitation basics in software development and marketing.