Graceful Allyship / Graceful Masculinity: Parshas Shemos

Part of a periodic Torah series on graceful masculinity and Jewish values.

וַיְהִי בַּיָּמִים הָהֵם, וַיִּגְדַּל מֹשֶׁה וַיֵּצֵא אֶל-אֶחָיו, וַיַּרְא, בְּסִבְלֹתָם; וַיַּרְא אִישׁ מִצְרִי, מַכֶּה אִישׁ-עִבְרִי מֵאֶחָיו.

It happened in those days that Moses grew up and went out to his brethren and saw their burdens; and he saw an Egyption man striking a Hebrew man, of his brethren. (Exodus 2:11)

Despite the brutal enslavement of his people, Moshe grows up safely cocooned in Pharaoh’s household. As the adopted son of Pharaoh’s daughter, Moshe is protected from the torment and endless labors of Israel. Yet, as he grows older he chooses to turn away from his own comfort to see his brothers’ suffering.

His evolution is heart-centered. Rashi explains that he “placed his eyes and heart to be distressed over them.”1 In not averting, but aligning his eyes and heart, he unites against their oppression where his allyship was the natural consequence of feeling the connectivity of humanity.

We find this reflected in the prayer that we offer during the Torah service: אַחֵֽינוּ כָּל בֵּית יִשְׂרָאֵל הַנְּ֒תוּנִים בַּצָּרָה As for our brethren, the entire House of Israel who remain in distress and captivity… Although the entire people are not literally “all in distress”,2 the pain of the individual is the pain of the whole, and we must all feel it personally.

This act of allyship was not without a cost. It came at the expense of his own privilege. Midrash Tanchuma relates that Pharaoh had put Moshe in charge of the royal household. Yet when Moshe aligns himself with the suffering of others and defends them from the cruel taskmaster, Pharaoh turns on him and he is forced to flee. In just three verses Moses goes from running Pharaoh’s affairs to being on the run, fearing for his own life.3

The story reads as if Moses lost the option of working from within and being an agent of change, but in truth it was this act that allowed him to be worthy of being truly impactful. The Midrash sees Moses’s focus on the enslaved Hebrew, both as the singular act that merited his unique closeness to G-d, and also as part of a daily spiritual practice of micro-affections.

He was subversive and his subversiveness was an act of resistance.

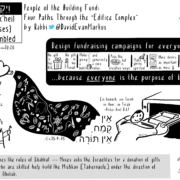

The Midrash comments on our verse: “And he looked on their burdens.” What is, “And he looked?” For he would look upon their burdens and cry and say, “Woe is me unto you, who will provide my death instead of yours…” Rabbi Eliezer the son of Rabbi Yose the Galilean said: [If] he saw a large burden on a small person and a small burden on a large person, or a man’s burden on a woman and a woman’s burden on a man, or an elderly man’s burden on a young man and a young man’s burden on an elderly man, he would leave aside his rank and go and right their burdens, and act as though he were assisting Pharaoh.”

Moshe’s intervention is seen by the rabbis as the merit necessary for G-d’s reciprocity of divine intervention. “The Holy One Blessed is G-d said: You left aside your business and went to see the sorrow of Israel, and acted toward them as brothers act. I will leave aside the upper and the lower [i.e. ignore the distinction between Heaven and Earth] and talk to you. Such is it written, ” And when the LORD saw that [Moses] turned aside to see” (Exodus 3:4). The Holy One Blessed is G-d saw Moses, who left aside his business to see their burdens. Therefore, “God called unto him out of the midst of the bush”4

Moshe eventually becomes the spokesperson for G-d because of his heart forward posture. King Solomon alludes to in the verse: אֹהֵב טהור לֵב חֵן שְׂפָתָיו, רֵעֵהוּ מֶלֶךְ

A pure-hearted friend, his speech is gracious; he has the king for his companion.5 The King in this verse is a reference to G-d,6and the “friend” to Moshe whose grace-filled speech enables him to be God’s companion.7 The sincerity of Moses’ heart made his speech graceful. His heart and mouth were aligned with each other. Flattery, חנף, by contrast, is the additional disingenuous speech, פה, over grace חן.8

The voice of an ally must originate in the heart as an internal response to whatever agonizing humanitarian failure one is witnessing. It also empowers us to speak truth to power. The heart is a muscle that requires work and watchfulness to develop. We are taught9 that the entire purpose of every mitzvah is to fix and restore the heart.10 Indeed immediately after Moshe flees Pharaoh we are told about his activism at the well, coming from the same source of advocacy.11

This week, we start reading the book of Exodus and the atrocities of enslavement, torment and infanticide. The Bal Haturim observes that the first word “שמות”, is an anagram of שְׁנַיִם מִקְרָא וְאֶחָד תַּרְגּוּם, the rabbinic injunction to read the weekly Torah portion twice in Hebrew and once in translation.12 The commentaries are curious about the placement of this teaching; why here?

There is often an urge to try and avoid, and even deny, uncomfortable or difficult realities. Perhaps the timing of this reminder is especially critical here to instruct us that when we are made aware of injustices – our own or others – we should not turn away but instead look closer, and then look again, to understand why it happened to make sure it stops and never happens again.

Parashat Shemos also begins a period of time known as “shovavim,” an acronym of the upcoming Torah portions, meaning to return. Central to this story of development and maturity is a shift from self-focus to caring for others. These weeks collectively narrate the birth and growth of the Jewish nation and the development of Moses as the Israelites’ leader. In recounting both Moshe’s and the Jewish people’s progress they provide us with the scaffolding to support our own work as individuals, encumbered by the needs of the community.13 Redemption comes when we love others as ourselves, not as others.

1.נָתַן עֵינָיו וְלִבּוֹ לִהְיוֹת מֵצֵר עֲלֵיהֶם↩

2. Zahav Misveh↩

3. Rashi 2:11↩

4. Midrash rabbah 1:27↩

5. Proverbs 22:11↩

6.Gra↩

7. Bamidbar Rabbah 15↩

8. ר.מ.ד. וואלי↩

9. Kad HaKemach, Shavuot 1:2↩

10. ודבר ידוע כי כל מצות שבתורה אינן אלא לתקן הלב כי הלב הוא העיקר↩

11. Exodus 2:15-16↩

12. ש.מ.ו.ת. שְׁנַיִם מִקְרָא וְאֶחָד תַּרְגּוּם↩

13. שובבים = מיצר ודואג Shovavim” has the numerical value of “oppression” and “worry”↩

By Rabbi Mike Moskowitz.