Why we trash(ed) our shuls for Tisha b’Av

Many liberal Jews ignore Tisha b’Av, or don’t know it’s there. For many of those whom we serve, Tisha b’Av is either a non-event or a great time to be on vacation. Who wants to sit on the floor and bewail the fall of one Temple 2000 years ago, and another centuries before? Most of us don’t yearn for a return to sacrificial cult anyway, so there’s often ambivalence — if liberal Jews are aware of Tisha b’Av at all.

Jews who are Orthoprax are more likely to be aware of the day and what it commemorates, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they’ve experienced it in a way that spiritually “works.” A full life of the spirit involves body, heart, mind, and soul; Tisha b’Av should awaken all of these.

Enter — literally — the trashed shul.

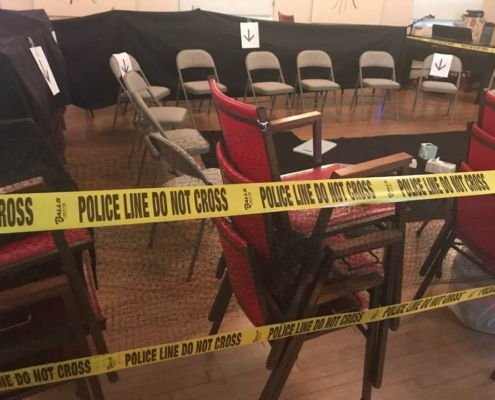

“Trashed” sanctuary, Temple Beth El of City Island, Bronx NY, 2017.

“Wrecking” the sanctuary

For several years now, both of us have maintained a practice of “wrecking” our shul sanctuaries before Tisha b’Av, and then restoring them as part of the holiday’s journey out of the depths.

Trashing the shul telescopes time, linking then with now. It evokes the fall of the first Temple, the fall of the second Temple, pogroms and other historical traumas, alongside today’s disturbing currents of rising antisemitism. Trashing the shul uses tools of stagecraft (scenery, lighting, design) and tangible realities (the darkened room, chairs overturned amidst visible markers of destruction) to arouse a spiritual response to tragedies both ancient and contemporary.

This is a way to both teach and embody descent for the sake of ascent. We overturn the shul precisely in order to set it aright again, and in so doing to reconsecrate our hands and hearts to the coming teshuvah journey and to the work of healing the broken world. The shock of it can open the heart. In the overturned space, there’s an opportunity to overturn our own resistance, to break through our own walls that keep us from feeling. Authentic spiritual life asks us to feel. Setting the stage in this way primes our bodies and hearts to do just that.

Runways and risks

Tisha b’Av begins the experiential runway to the Days of Awe. This day is the low point from which we begin to rise toward the holidays. Sitting in a “wrecked” shul helps us to feel that low point. We aren’t just reading about trauma “back then.” We’re feeling into it here and now.

Meanwhile, the work of wrecking / trashing the shul becomes a runway into Tisha b’Av itself. This is a teaching opportunity, especially for communities that may not be very aware of 9Av or how it can serve as a springboard for the teshuvah journey.

Trashing the shul is spiritually risky. It can be activating, especially where there is PTSD, trauma, or epigenetic trauma. We make a point of telling those whom we serve in advance what we’re doing and why (via newsletter articles, e-mails, conversations, digital announcements, etc). This acts as a partial inoculation against unconscious trauma response. We still need to be attuned to the possibility of trauma response and ready to respond pastorally.

One year, volunteers set the stage for Tisha b’Av a bit early, not realizing that a committee meeting was slated to take place at the synagogue that evening. When committee members arrived, they thought that the shul had actually been ransacked. They were horrified… as were we, because we never intended for anyone to encounter the destruction outside of the ritual container. From this we learned to always put a sign on the sanctuary door once the room has been prepared, so that anyone who approaches knows what’s happening and why.

In a word, the “why” is to help us open our hearts and feel grief. But not for the sake of wallowing. We feel into communal grief for the sake of change, and because our tradition teaches that the depths are precisely where hope is born. Midrash (Eicha Rabbah 1:51) teaches that moshiach (the messiah) is born late in the day on Tisha b’Av. Out of our deepest sorrow comes the potentiality for the world’s most needed transformation. The going down is the first step toward rising back up again. It’s important that we feel the depths — and it’s equally important that we help people lift out of those depths again. The point is for the grief to help launch us toward action, hope, and transformation.

“Trashed” sanctuary, CBI 2021

How we do it:

The practical steps are simple:

- Overturn chairs. (Leave a few chairs for those who physically can’t sit on the floor or on low stools, but perhaps choose less-comfortable ones than usual.)

- Strew some tallitot and kippot on the floor.

- Knock over a trash can or two. (Don’t put actual garbage on the floor, but crumpled papers work well.)

- Remove the Torah scrolls safely from the ark, and drape the ark in black fabric.

- Place yahrzeit candles around the room.

- If you have American and Israeli flags, tip them over (let them be askew / leaning on the wall if not actually on the floor).

- Put a sign on the door to let people know what’s happening and why.

It’s important not to harm the Torah scrolls, tallitot, siddurim — or for that matter the flags, or books, or the building writ large. The idea is to create a felt sense of destruction without actually destroying anything.

“Detention center” sanctuary, Temple Beth El of City Island, Bronx, NY, 2019

If you want to explore a more elaborate setup, there are ways to do that. One year TBE was turned into a detention center. Another year there was yellow police caution tape to evoke a crime scene, and a swastika made out of kippot on the floor. One year volunteers muddied a pair of big boots, made footprints on pieces of paper and placed those on the floor, as though a jackbooted thug had walked through CBI. Last year at CBI there were Xerox copies of Mourner’s Kaddish, and matches were used to singe the edges of the pages so they looked like they had come from books that had been burnt. The basic setup is simple, and you can adapt as needed based on what you have at hand and what issues feel most “live” in a given year.

We’ve learned that people will sit in the back if that option is available to them. There’s a natural tendency to want to distance oneself from destruction. So, ensure that there is no seating far away. Design the space so that people have to draw near to the desecration. It’s also important that we be near each other (presuming appropriate pandemic precautions), because the losses we mark here are communal, and we need to feel them together.

Plan your service so that there is an arc from feeling the brokenness, to going down into the depths, to bringing people back out again. Putting the sanctuary back together is a physical action that can elicit the emotional and spiritual experience of rising up from the depths. We don’t break people’s hearts and then leave them there: that would be spiritual malpractice. Together we crack our hearts open so that grief can flow out — and so that hope can flow in. And in collaborating on putting everything aright again, we lay down neural, emotional, and spiritual pathways of community, rebuilding, and hope.

It can be useful to narrate the rebuilding so it happens as intended. Do you want people to be righting the overturned chairs and cleaning up during the final song, or afterwards? In sacred silence, or while chatting (in contrast to the somber silence at the start), or while we sing a niggun? Any of these can work, but it’s good to know which one you’re going for so you can give participants the sense of safety that comes with clear instructions and expectations.

Does it “work”? (How do we know?)

This practice “works,” spiritually, if it: 1) moves people, 2) draws people in, 3) makes Tisha b’Av feel real and alive, and/or 4) enriches the teshuvah journey that will follow.

We know that this practice works because people have told us so. Congregants have told us that they didn’t expect to feel anything much at Tisha b’Av — maybe they’d never felt any connection to the Temples, or hadn’t understood why this holiday mattered — but this experience helped them feel. They have told us that this experience cracked their hearts open, and brought them through catharsis toward hope. They have told us that this first step on the teshuvah journey subtly and pervasively impacts the weeks and months that follow.

We’ve also both seen Tisha b’Av attendance increase at our shuls over the years we’ve been doing this. At both of our shuls there are now congregants who remember this practice from year to year, volunteer to help with setup and share the work of rebuilding together with gusto, and look forward to the day as a deep dive into emotion and the springboard that launches the teshuvah journey of the Days of Awe.

More people take part in Tisha b’Av in our communities now than before we launched this tradition. And many of our new Tisha b’Av “regulars” are people for whom Tisha b’Av had previously been either impenetrable or unknown. This practice “works” because it opens hearts to the meaning of the day, and deepens the teshuvah journey that follows.

Rabbi Rachel Barenblat, a founding builder at Bayit, serves Congregation Beth Israel of the Berkshires. Rabbi David Markus, chair of the Bayit board and a founding builder at Bayit, serves Temple Beth-El of City Island.