As Yourself: Acharei Mot-Kedoshim

Part of an ongoing series that explores Torah through an ethic of social justice and building a world worthy of the Divine

Last winter, my HIAS colleagues took a group of rabbis on a delegation to the US/Mexico border. The purpose of the delegation was witnessing and learning about the situation on the ground for families and individuals seeking to claim asylum in the United States, as is their right under US and international law. One of the pictures from that trip has haunted me ever since – an image of people wading across the Rio Grande from Ciudad Juarez trying to reach El Paso, one of them carrying a child wrapped in a blanket.

Last year, more than 800 people died while attempting to make that crossing. We don’t know how many of them were children.

One of the core principles of the refugee Torah I teach for HIAS is ‘love the stranger’ – a commandment repeated more times than any other in the Torah. Sometimes, this teaching appears to be in tension with the strand in the Torah that is working to keep the Israelites separate and distinct from the peoples surrounding them.

This week’s double parsha is a powerful example of this tension. Acharei Mot is filled with prohibitions, lists upon lists of things not to do, and those prohibitions apply equally to the Israelites and the ‘stranger who lives with [them]’. This is striking because many of the prohibitions are for the explicit purpose of distinguishing the behavior of the Israelites from that of the surrounding nations. The behavior of those nations, of course, ranges in the imagination of the biblical author from ritually distinct to downright abhorrent. So, Acharei Mot’s prohibitions simultaneously distance our ancestors from their neighbors and create an implied solidarity between the Israelites and the ‘neighbors’ who are closest to them – the strangers who dwell in their midst, and are obliged to abide by their laws.

How we imagine the values and practices of those we think of as ‘other’ has material implications for how we treat them. Even as we work to uplift and uphold what we see as the highest values of both the Jewish and American civilizations, are we extending our compassionate imagination outward? Are we standing in solidarity with the ‘strangers’ who dwell with us?

In Kedoshim, the stranger is listed along with the poor person in the category of the economically vulnerable who are entitled to the unharvested corners of the field. And we have this blindingly clear statement in Leviticus 19:33-34: “When strangers reside with you in your land, you shall not wrong them. The strangers who reside with you shall be to you as your citizens; you shall love each one as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt: I יהוה am your God.”

I read these verses as saying that it is not enough to ‘not wrong’ the stranger – to not be oppressors ourselves. Rather, we are obligated to work to end the oppression of strangers as we would work to end our own oppression – that is what it means to ‘love the stranger as yourself.’

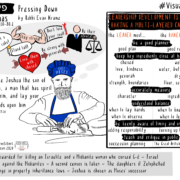

The verses come at the end of chapter 19 of Leviticus. At the very beginning of chapter 20, we get the prohibition against sacrificing our children to Moloch. In the strongest possible terms, the Torah says we are not to sacrifice our children on the altars of false gods. Like with the prohibitions in Acharei Mot, the ‘stranger who lives with the Israelites’ has to follow this same rule. And the verses from Kedoshim teach us that it is not merely our own children who we must keep safe, but that we are obligated to protect the stranger’s child as our own.

Given our country’s current policies which deny entry to almost all asylum seekers at the U.S.-Mexico border, families like the one in the photo are largely turned away, often to extreme danger, before even being able to make a case that they should be granted asylum. What protection should we instead be offering to the children and families coming to our borders in hope of a better, safer, life? How can we live in to our obligations as Jews and as Americans to provide refuge, stability and hope to those in need?

At HIAS, we work every day to welcome the stranger and protect the refugee. Learn more and join our work here: Welcome the stranger. Protect the refugee. (hias.org)

Rabbi Megan Doherty is the Senior Educator in Community Engagement at HIAS.

Artist Steve Silbert is on the Bayit Board of Directors and is Lead Builder for Bayit Games.