Being Seen: Tazria / Metzorah 5783

Part of an ongoing series that explores Torah through an ethic of social justice and building a world worthy of the Divine

I was in a shoe store last weekend to get fitted for a pair of walking shoes. There was a nifty machine that measured my feet, and then another even niftier one that checked my gait, in order to fit me scientifically for the best shoes they had for my body.

The machines read a foot that wasn’t mine: wide, low arch, new, larger, shoe size. I have short, narrow feet, and a high arch. The machines didn’t see me. But that wasn’t the problem, really; I don’t necessarily expect a machine to see me. The problem was that the person fitting me, she didn’t see me either. She saw the machine and what it read, but she failed to look at my feet. When I suggested to her that the readings were incorrect, she got me back on the same machines, agreed that the second reading was different from the first, but continued to insist that what she read on the machine was what was true. She never looked at me.

She didn’t see me.

What does this have to do with Tazriah/Metzorah?

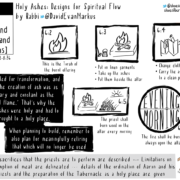

At its core, the ritual of tzara’at is a ritual of seeing and being seen.

Most of Parshat Tazriah/Metzorah elucidates the ways in which the Kohen is asked to examine a skin ailment, and how to identify the things that he sees. In every case, the Kohen must look and see and examine myriad variations dealing with each individual instance in front of him. It is only when the Kohen is sure of a person’s condition that the person is asked to leave camp. Once that happens, there is an even more explicit set of instructions for returning a person to the camp once he or she is healed.

וְהַצָּר֜וּעַ אֲשֶׁר־בּ֣וֹ הַנֶּ֗גַע בְּגָדָ֞יו יִהְי֤וּ פְרֻמִים֙ וְרֹאשׁוֹ֙ יִהְיֶ֣ה פָר֔וּעַ וְעַל־שָׂפָ֖ם יַעְטֶ֑ה וְטָמֵ֥א ׀ טָמֵ֖א יִקְרָֽא׃

As for the person with a leprous affection: the clothes shall be rent, the head shall be left bare, and the upper lip shall be covered over; and that person shall call out, “Impure! Impure!”

כל־יְמֵ֞י אֲשֶׁ֨ר הַנֶּ֥גַע בּ֛וֹ יִטְמָ֖א טָמֵ֣א ה֑וּא בָּדָ֣ד יֵשֵׁ֔ב מִח֥וּץ לַֽמַּחֲנֶ֖ה מוֹשָׁבֽוֹ׃

The person shall be impure as long as the disease is present. Being impure, that person shall dwell apart—in a dwelling outside the camp.

“Impure, impure” is what the person shouts out to the camp as he leaves. To the modern sensibility this can be jarring.

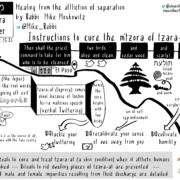

The Talmud teaches, however, that:

כִּי הֵיכִי דְּלִיחְזְיוּהּ אִינָשֵׁי וְלִיבְעוֹ עֲלֵיהּ רַחֲמֵי. כִּדְתַנְיָא: ״וְטָמֵא טָמֵא יִקְרָא״. צָרִיךְ לְהוֹדִיעַ צַעֲרוֹ לְרַבִּים, וְרַבִּים יְבַקְּשׁוּ עָלָיו רַחֲמִים. אָמַר רָבִינָא: כְּמַאן תָּלֵינַן כּוּבְסֵי בְּדִיקְלָא — כִּי הַאי תַּנָּא.

As it was taught in a baraita with regard to the verse: “And the leper in whom the plague is, his clothes shall be ripped and the hair of his head shall grow long and he will put a covering upon his upper lip and will cry: Impure, impure” (Leviticus 13:45). The leper publicizes the fact that he is ritually impure because he must announce his pain to the masses, and the masses will pray for mercy on his behalf.

The Ba’al Shem Tov expands on this, saying,

וטמא טמא יקרא. ודרשו רבותינו ז”ל (שבת דס”ז ע”א) צריך להודיע צערו לרבים ורבים יבקשו עליו רחמים, בשם הבעש”ט זלהה”ה. מה שאומרים העולם שאחר שריפה ר”ל ווערט מען רייך, כך הוא האמת, מען ווערט באמת רייך, והוא נר”ו אסברה קצת, דאיתא בגמרא יודיע צערו לרבים ורבים מבקשין עליו רחמים.

והר”ז זלה”ה אמר שגעגועים של ישראל הם תפלות, ודרך העולם שיש להם געגועים ורחמנות גדולה על מי שנשרף הונו ר”ל, וחפצים שיתרומם קרנו וכו’:

(מדרש פינתס ד”כ ע”ב).סליק פרשת תזריע בס”ד

Impure Impure he will cry out: […]In the name of the BeShT, what this means is that always, after healing, Mercy upon us, we are made “rich”. This is the truth. And he, may God protect him and save him, gains a little bit of hope. As we find in Gemara, he announces his trouble to all, and all ask for mercy for him.

Razal said that the hopes of Israel are prayers, and the way through the world is with longing and great mercy for those whose [things] have been burned, heaven forbid, and that desire is elevated for his glory.

(Tazria, Comment 3)

It’s a question of being seen:

The Besht teaches that we need to see the person in need in order to pray for their healing. But what does prayer actually do?

For the Besht, prayer happens in community. It might even be that praying together is part of what makes a community, in his paradigm. In the United States today, the idea of prayer has come to seem at once loaded and ineffective. We’re tired of “hopes and prayers” after every new tragedy: those calls have come to feel meaningless. What’s missing here is the SEEING of those who are suffering. It’s too easy to choose not to see what’s broken, including the death of loved ones by violence and illness and disability.

For the Ba’al Shem Tov, prayer is active, not passive. We’re not simply holding “thoughts and prayers” as the United States Senate would have us do. For us as Jews, prayer culminates in action. Prayer leads us to actively work for healing of the individual, and the world. The Besht calls this “elevating [our] yearning to the glory of the divine,” and teaches that when we do this, our blessings are without measure.

Abraham Joshua Heschel wrote that when he marched with MLK, his feet were praying. He embodied the integration of prayer and action, crying out to God while also working for justice in the here-and-now.

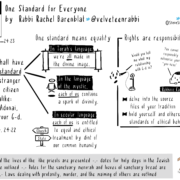

Tazria, and then Metzorah, remind us how important it is to be seen – especially when we are suffering or struggling. Once it was the kohen’s job to see each person and their needs; today that job falls to all of us.

For a contemporary version of Tzara’at, we need look no further than COVID, specifically “Long COVID.”

According to the Atlantic, “Long COVID is being erased, again”. Ed Yong writes that while the issues, causes, and symptoms of infections of Coronavirus have been well documented, the emphasis has been on the deaths and hospitalizations of those affected. But, he writes

“What was once outright denial of long COVID’s existence has morphed into something subtler: a creeping conviction, seeded by academics and journalists and now common on social media, that long COVID is less common and severe than it has been portrayed—a tragedy for a small group of very sick people, but not a cause for societal concern.”

This is, to be blunt, exactly what the ritual of Tzara’at is designed to circumvent. Although “Almost every aspect of long COVID serves to mask its reality from public view”, the ritual of Tzara’at brings matters of sickness and healing into the reality of daily life. The person who’s afflicted actually tells everyone of their affliction, and the community is there for them.

That’s the world I want to live in. Where each of us is wholly seen, and our needs are met, and prayer implies action toward healing, for us and for the world.

R. Cyn Hoffman is a member of the Bayit Board of Directors.