Coming in February: Daughters of Eve

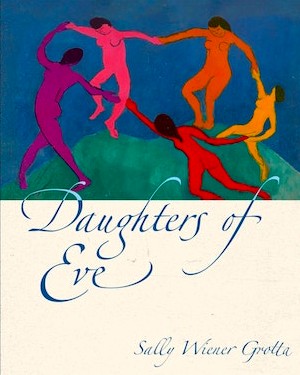

When you think of Eve and Lilith, Sarah and Hagar, Rebekah, Esther, and the other women of the Hebrew Bible, who are they to you? For me, they are “flesh-and-blood individuals whose fragmentary stories generate more questions than answers, inviting us on an adventure of discovery – about them and about us.” That’s the inspiration behind my newest book Daughters of Eve.

When you think of Eve and Lilith, Sarah and Hagar, Rebekah, Esther, and the other women of the Hebrew Bible, who are they to you? For me, they are “flesh-and-blood individuals whose fragmentary stories generate more questions than answers, inviting us on an adventure of discovery – about them and about us.” That’s the inspiration behind my newest book Daughters of Eve.

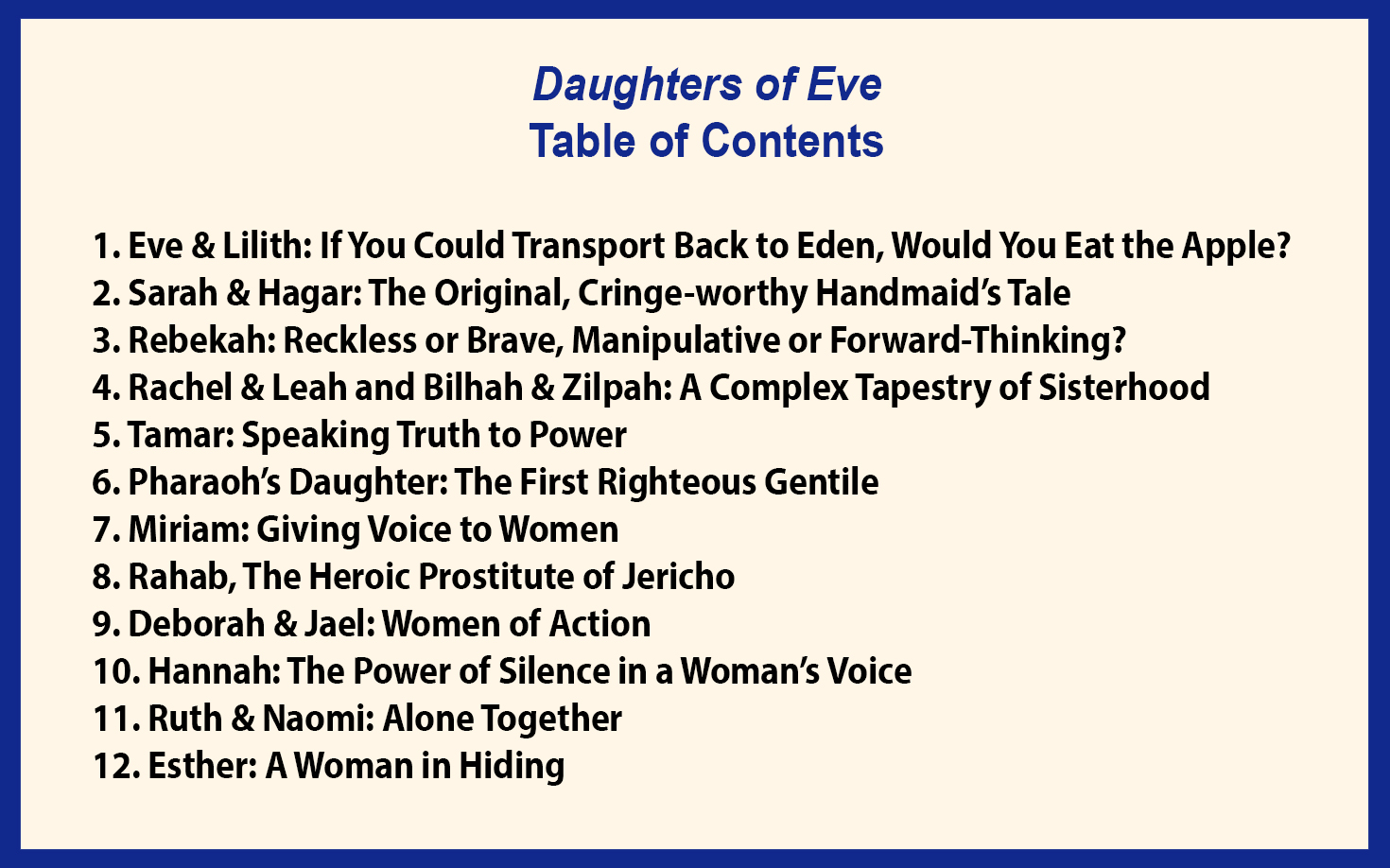

Daughters of Eve is an essay collection and discussion workbook, which explores the nature of living in the 21st century through the filter of the stories of the women of the Hebrew Bible. It’s designed to facilitate exchanges about how our reflections on our ancient matriarchs influence and reveal who we are today. For groups that meet once a month, Daughters of Eve‘s 12 essays and related questions will provide a year’s worth of discussions.

Daughters of Eve is filled with stories and questions that are designed to challenge and encourage dialog. However, I don’t offer definitive answer. Instead, I’ve designed the workbook to guide groups in delving more deeply, igniting a mutually respectful sharing of diverse ideas that will, in turn, generate more questions.

If this sounds compelling to you, you can support this project at Kickstarter! And here’s a sample chapter to whet your appetite:

Rachel & Leah and Bilhah & Zilpah: A Complex Tapestry of Sisterhood

Genesis 29-31

Rachel and Leah were sisters and mothers. This simple statement delineates the responsibilities and expectations that shaped their days, and the reach and limits of their existence. Further complicating Rachel and Leah’s lives was the fact that they shared a husband – Jacob – not only with each other, but also with their handmaids Bilhah and Zilpah.

These four women were the mothers of Jacob’s twelve sons – the progenitors of the twelve tribes of Israel. (The text also names one daughter – Dinah.) But peel back the heavy curtain of biblical history, and we see a sisterhood that was a minefield of divided loyalties and conflicting needs, creating a complex tapestry of compassion, envy, humiliation, and reciprocity, in which two of the women have no voice.

While Rachel and Leah had a life together before they were each married to Jacob, their story starts with a deception that neither had any power to prevent. Jacob had labored seven years for the right to marry Rachel (the woman he loved), but their father Laban substituted Leah as the bride, hiding her identity under a veil. So why didn’t Jacob suspect a thing, even as he and Leah consummated the marriage? How could he not know the difference between the two women?

According to classical midrashim, Rachel was determined to protect Leah from being mortified by the untenable situation. Some say that Rachel shared with her sister the “signs” she had given Jacob to aid him in recognizing Rachel as his bride even if she were veiled. (Rachel apparently knew her father wasn’t to be trusted.) One ancient midrash goes so far as to imagine Rachel hiding under the marriage bed that first night, so that whenever Jacob spoke to his bride, he would hear Rachel’s voice. How humiliating and heartbreaking that would have been for both women. Putting aside any doubts that such a scene could have taken place and that Jacob could have been taken in by it, the crux of these extrapolations was to affirm that Rachel protected and cared for Leah. After all, isn’t such self-sacrificing compassion supposed to be an essential facet of being a sister?

When Rachel became Jacob’s second wife, things deteriorated between her and Leah. The narrative drips with the tension between them, though the Torah gives us only snippets of snipes and indirect complaints to illustrate the sisters’ rivalry. The central problem was that Leah, whom Jacob did not love, was winning the “baby contest” by popping out one son after another, while Rachel, who remained barren, had Jacob’s love. We can wonder, however, about the nature of that love when he refused Rachel’s request that he pray to God to remove her infertility. After all, he reasoned, it clearly wasn’t his fault that she had failed to produce children.

Rachel became so desperate for a son that she gave Jacob her handmaid Bilhah. Not to be outdone, Leah then gave Jacob Zilpah. The situation is similar on the surface to the story of Sarah and Hagar, in that the handmaids’ children fathered by Jacob counted as belonging to their mistresses. Rachel became pregnant soon after Bilhah, just as Sarah did.

However, Zilpah and Bilhah’s situation was different from Hagar’s. Beyond the fact that they were little more than extra wombs, with no story of their own, one tradition claims that the handmaids were Rachel and Leah’s half-sisters, having been born to Laban’s concubine. If that were so, it says a lot about Laban that he gave Bilhah and Zilpah to Rachel and Leah as wedding gifts – and about Rachel and Leah who accepted and used them.

While this biblical story of sisterhood reads like a soap opera, one last scene between Jacob, Leah and Rachel shows another aspect of the sisters’ relationship. After twenty years of living with and serving Laban, Jacob consulted his two wives about returning home. He noted how poorly their father had treated him, though God had helped Jacob accumulate wealth despite Laban’s subterfuges. In one voice, Rachel and Leah agreed, acknowledging that they owed Laban no loyalty, since to him they were now outsiders of no value. As in the beginning of their story when Rachel supposedly spoke for both of them, the two sisters were now unified, as if they were standing back-to-back, facing whatever or whoever might challenge either of them.

One of my early memories is of sitting at the kitchen table with my sister Amy and our parents. My mother asked Amy and me, “Who do you think are the two people most closely related at this table?” I couldn’t have been more than six years old, and I turned to my big sister for the answer. She was silent, too. I remember the look my parents gave each other, and how it made me feel secure and warm, and that in my mind I was sure the answer would be that Mom and Dad were the two who were the closest. Instead, my father said to Amy and me, “The two of you.” Mother added, “You are made of the same flesh and blood. Whatever happens between the two of you, remember that always.”

Over the years, I’ve accumulated several other sisters: one by marriage and others by choice. Naturally, there is a hierarchy to these relationships. The longer the relationship, the stronger are the ties that hold us together, and the deeper the disappointment and hurt when something goes awry between us. I have seen how miscommunications, mistakes, and emotional turmoil can distort love into anger – or worse, into apathy. On the other hand, among the women who have remained integral parts of my life, I have also seen how investments in love, time, and acceptance – and with Amy, also in flesh and blood – have seen us through the rough patches.

Rachel, Leah, Bilhah and Zilpah formed a sisterhood, perhaps of blood, definitely of proximity and marriage. But what was the nature of that sisterhood? I would love to have been a fly on the wall, listening to these sister wives and sister slaves. I wonder what conversations Rachel and Leah had when no man, servant or child was around. Did they form the same kind of unit that Amy and I have: sometimes intimate confidants, sometimes little more than distant thoughts on the periphery of our busy lives, but always with an underlying foundation of unshakable love, regardless of any other emotions or reactions we might feel about each other from one moment to the next? And I wonder about Bilhah and Zilpah. Did they ever find their voices?

Additional Questions

- How is a sisterhood different from a close friendship between two women?

- Why do sisters (either by blood or by choice) turn against one another? How do they find a path back to each other?

- If the original biblical text about Rachel, Leah, Bilhah and Zilpah had been written by a woman, how do you think it might have differed from the one we read in Genesis?

- If you could give a voice to Bilhah or Zilpah, what do you think they might say about or to Rachel and Leah?

- How do you think the conversations among the four women changed after they became mothers?

Sally Wiener Grotta is an award-winning writer, photographer, and speaker whose books include The Winter Boy (a Locus Magazine Recommended Read) and Jo Joe (a Jewish Book Council Network Book). Her recently published feminist science fiction collection Of Being Woman (NobleFusion Press) has been compared to the works of Ursula K. LeGuin, William Gibson, Samuel R. Delany, and other icons of literature. Her articles, essays, and stories have appeared in scores of publications. As a journalist, Sally has traveled on assignment throughout the world, to all the continents, plus many remote islands, covering a wide diversity of cultures and traditions. Sally’s far-ranging experiences flavor her writing and presentations with a sense of wonder, appreciation for human potential and a healthy dose of common sense.

Sally Wiener Grotta is an award-winning writer, photographer, and speaker whose books include The Winter Boy (a Locus Magazine Recommended Read) and Jo Joe (a Jewish Book Council Network Book). Her recently published feminist science fiction collection Of Being Woman (NobleFusion Press) has been compared to the works of Ursula K. LeGuin, William Gibson, Samuel R. Delany, and other icons of literature. Her articles, essays, and stories have appeared in scores of publications. As a journalist, Sally has traveled on assignment throughout the world, to all the continents, plus many remote islands, covering a wide diversity of cultures and traditions. Sally’s far-ranging experiences flavor her writing and presentations with a sense of wonder, appreciation for human potential and a healthy dose of common sense.