Graceful Progress / Graceful Masculinity: Emor

Part of a periodic Torah series on graceful masculinity and Jewish values.

Part of a periodic Torah series on graceful masculinity and Jewish values.

וּסְפַרְתֶּם לָכֶם, מִמָּחֳרַת הַשַּׁבָּת, מִיּוֹם הֲבִיאֲכֶם, אֶת-עֹמֶר הַתְּנוּפָה: שֶׁבַע שַׁבָּתוֹת, תְּמִימֹת תִּהְיֶינָה.

You shall count for yourselves, from the morrow of the rest of the day, from the day when you bring the omer of the waving, seven weeks, they shall be complete. (Leviticus 23:15)

We find the “Exodus of Egypt” mentioned fifty times in the Torah (Gra), just as the world was created with fifty gates of wisdom (Rosh Hashanah 21b). We also find that when the Israelites left Egypt they were on the 49th level of spiritual impurity (Zohar P’ Yisro) and on the brink of reaching spiritual annihilation. Remarkably, only 7 weeks later when they stood at Mount Sinai, they had reached the 49th level of holiness. (Rokeach)

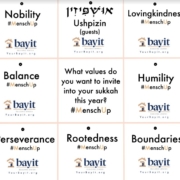

Every year we re-experience the transition, from going out of Egypt to receiving the Torah, by counting the 49 days of the Omer. It is intended to be a deeply personal and individualized process of really working on one’s own evolution and development. The Talmud (Menachus 65b) understand the word “לכם” you, as “each and every one” shall count for yourselves.

These seven weeks are described in the verse as temimot, perfect and whole. Rashi explains temimot as meaning complete, in that we must begin counting on the second night of Passover, so that the first day of counting isn’t deficient. The midrash though understands temimot not as a technically complete count, but as complete in a spiritual sense. The midrash explains:

אֵימָתַי הֵן תְּמִימוֹת? בִּזְמַן שֶׁיִּשְׂרָאֵל עוֹשִׂין רְצוֹנוֹ שֶׁל מָקוֹם

“When are these [seven weeks] complete? When Israel is doing the will of the G-d”.

Clearly something about the verse is bothering the midrash that it was moved to reframe it. What does doing the Divine will have to do with counting to 49? Additionally, the task of this period of time is specifically to shift the negative into the positive. Rav Vachtfolgel Z”tl observes that this is why the word “שבתות” Shabbats are used as opposed to shavuot, meaning weeks – because it is about sanctifying oneself like the shabbos. How then are we meant to see the past as perfect if we are invested in changing it for the future?

The Ksav V’kabala explains temimut as an indicator of quality, not quantity. When a person is focused on doing their best, whatever that might be, it is called complete. It is so specific to the moment that even the same person should be seen differently, depending on where they are holding.

Our rabbis also see an allusion, in the verse, to Abraham who is told lech-lecha, go for yourself. The midrash points out that G-d said those words to Abraham earlier in his spiritual journey, when he first left his father’s home, and again many years later, when he is commanded to sacrifice his son Isaac. The midrash continues by saying “and we don’t know which was a greater test.” An explanation is given, by the Slonimer Rebbe, that both of these tests were equally challenging because they reflected where Abraham was at the time. Comparing the two doesn’t help in evaluating the degree of difficulty of the moment.

We find a similar framing of the tam, the “simple son” in the Haggadah. The Vilina Gaon sees him as the counterpoint to the wicked son in that they are each equally focused on either coming closer or further away from G-d. Jacob too is described (Genesis 25:27) as a “simple man who sat in tents.” Jacob was simple in that there was no complexity of competing interests besides just doing the right thing.

Perhaps this is what the midrash is coming to answer: How can you claim that the seven weeks are tam – pure, perfect, and pristine – when it is clearly a work in progress? The important lesson being taught here is that the ideal is in flux. As we do our best to grow and change, every point along the way is tamim, or perfect. As we grow, so does the goodness, but those advancements don’t minimize or cancel the past.

It is for this reason that we find in Psalms (84:12) “Grace and glory does Hashem bestow; G-d withholds no goodness from those who walk in perfect innocence (בְּתָמִֽים).” Two people can do or say the same thing, but it can land very differently (Pele Yoetz). Chein, grace, is the difference in the way the action is perceived and it is determined by the intention and effort of the person in the moment.

If we can’t appreciate the changes that we are making for the good, because the comparison to the past highlights our shortcomings, we inhibit and deter future development. In repenting for unintentional transgressions we acknowledge that “had I known then what I know now, I would have acted differently.” When we are trying as hard as we can to develop into the best version of ourselves each moment, we immediately come to learn that the ceiling quickly becomes the floor. In reflecting back on earlier times “when we just didn’t know any better,” we need to be critical of society and the factors that contributed to that environment, but knowing better, and acting differently because of that wisdom today, is a holy accomplishment.

By R. Mike Moskowitz.