Building a Gingerbread Bayit

“Mom, let’s build a gingerbread house!” Maybe my nine year old got the idea because he was building a LEGO set while watching The Great British Bake-Off. He’s been on winter break from his elementary school, and for us that means lots of playdates, LEGO creations, and bake-off on Netflix. It also turned out to mean an opportunity to notice three lessons about building the Jewish future through baking a gingerbread bayit with my kid.

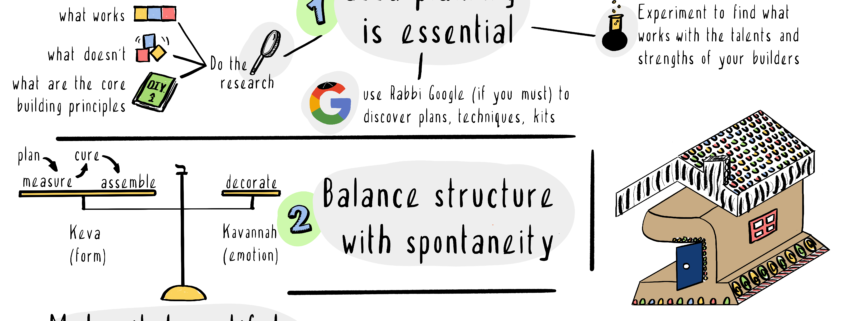

- The importance of good plans

I’d never built a gingerbread house from scratch. Fortunately the internet is full of advice on how to make a gingerbread house that has a reasonable chance of staying up. Step one was research. Learn what my forebears have done: what’s worked, what hasn’t worked, and what principles undergird the successful attempts so I could do my best to replicate them.

Rabbi Google suggested that in order for a gingerbread build to be successful, one needs templates (like these, provided by the New York Times) — and one needs to plan ahead. The most reliable recipes call for mixing a fairly stiff dough, baking house components, and then letting them rest for a few days to grow solid enough to be used as building materials.

Fortunately my son got the gingerbread building bug early enough in his winter break that we had plenty of time to research building techniques, shop for ingredients, make our dough, and let the cookies cure. If you want to build a sukkah or host a seder or celebrate Shabbat, you too can draw on the wisdom of received tradition… and if you get the idea a few days in advance, mah tov (how good that is!), because it gives you time to question, learn, and lay in supplies.

- Balance structure with spontaneity

A gingerbread bayit’s pieces need to be planned, measured, baked, cured, and assembled — that part takes readiness to follow a plan and accept the wisdom of received tradition. And then it needs to be decorated — that part takes creativity. In the collaborative duo of my son and me, one of us was more interested in planning and the other was more interested in decoration. (I’ll let you guess which one of us is which.) Meta-message: in assembling any building team, make a point of balancing skills, competencies, and interests.

Our sages had a lot to say about the appropriate balance of keva (structure or form: think the structure of a service, which is always the same) and kavanah (intention or heart: the emotion that we bring to the pre-established words, or the creative / interpretive versions of those words we can offer alongside or instead of the traditional ones.) In all of our building — whether we’re assembling a morning service, a Tu BiShvat seder, or a gingerbread home — that balance is how we enliven the forms of received tradition. Just don’t smear royal icing on your siddur.

- Make it beautiful, make it your own

Jewish tradition includes the concept of hiddur mitzvah, “beautifying a mitzvah.” This is the reason for elaborately decorated ritual items (candlesticks, kiddush cup), sacred spaces (sanctuaries, sukkot), and other meaningful objects (tzedakah boxes, mezuzot.) In making our ritual items and sacred spaces beautiful, we show extra love and care for the tradition, for our Creator, and for ourselves.

If you’re building a gingerbread bayit, this is a principle you’ve got to apply, along with gumdrops, rainbow sprinkles, and powdered sugar “snow.” No two gingerbread houses are the same, and that’s the whole point: the walls may be cookie-cutter, but their decorations shouldn’t be. And my son’s taste in gingerbread house décor may shift as he grows.

Just so with all of our building, edible or not. As a kid I loved the Passover seder because I got to belt out the Four Questions and then I got to hunt for the afikoman and get a prize. As an adult, I’ve loved building my own haggadah, and I thrill to the question of how to work toward freedom from constriction not only on an individual level but on a communal / national one. Making the seder “my own” means something different in my forties than it did in my twenties or in my childhood. And that’s as it should be. Responsiveness to our own change is baked in to the tradition.

*

Authentic spiritual life asks us to take all three of these seriously. To plan and learn and question and research and build. To honor wise structures and solid foundations even as we let our spiritual creativity soar. And to bring beauty, and our own growing and changing hearts, to everything we build.

Gingerbread sukkah next fall, anyone?

By Rabbi Rachel Barenblat. Sketchnote by Steve Silbert.