A Tisha b’Av of Hope

Many Jewish professionals I know secretly (a few, not so secretly) prefer to take off Tisha b’Av for any number of reasons. It’s too sad. It’s mere nostalgia that never can build a future-oriented Judaism. Programming is too sparsely attended. The theology (and especially theodicy) of a “God that allows destruction” is too difficult in these post-Holocaust generations. God forbid the Temple should be rebuilt that way. Some Jewish professionals I know do take off Tisha b’Av and pretend the day away, or metaphorically call it in.

I empathize with all of these reasons. Even so, to me, Tisha b’Av is too important to ignore. So this year, my community and I will honor Tisha b’Av very differently than we have in years past – owing to the many simultaneous crises of the last several years, and the emotional and spiritual state of so many people already struggling.

In case it’s helpful, read below a bit about what this year’s Tisha b’Av might be, and how it can serve the day’s deep emotional and spiritual purposes while taking advantage of a quirk in the Jewish spiritual calendar to focus on hope re-emerging from the brokenness of this season.

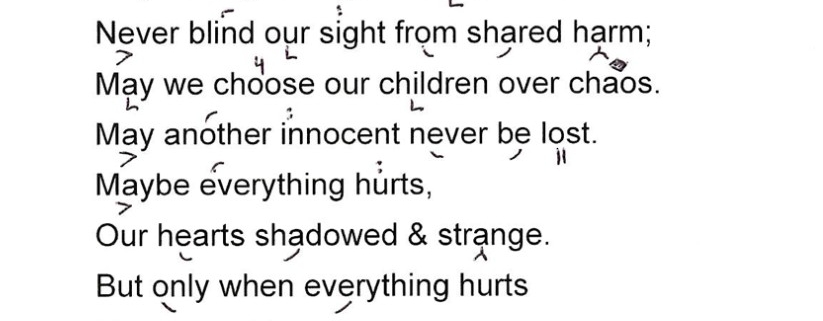

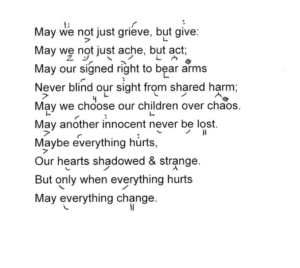

To illustrate the point, here’s a liturgical rendering of the amazing Amanda Gorman‘s “Hymn to the Broken” (2022), which she wrote after the school shooting in Uvalde, Texas, set to the mournful trope of Lamentations traditionally associated with Tisha b’Av. We can be broken and also roused to act. We can hurt and also heal. Even now. Especially now.

Above: a glimpse of part of the poem with trope marks. For the whole poem, and recording, click below:

Hymn for the Hurting [pdf with trope marks, also mp3]

What Tisha b’Av is Really About

Whatever else tradition usually associates with Tisha b’Av (e.g. eerie historical synergies of collective Jewish destruction and loss, from Temple days forward), Tisha b’Av serves at least two functions in the arc of the Jewish spiritual year.

First, Tisha b’Av holds a necessary place and time for collective grief, much as Purim holds a dedicated place and time for collective boundary-crossing joy. Both are parts of the ebb and flow of life, and thus must claim rightful places in the ebb and flow of the Jewish spiritual year so that our Judaism can serve and uplift the totality of life.

Second, Tisha b’Av launches the seven-week ascent to Rosh Hashanah, much like Passover launches the seven-week Omer count to the Revelation we honor and receive anew at Shavuot. Emotionally and spiritually, we need an effective runway into the High Holy Days, lest they appear so suddenly that we experience them as a vertical wall we can’t quite scale.

These two functions are too important to forget, cast aside or serve poorly. Therefore, so too is Tisha b’Av. So while I share some of the common practical and theological impulses to look away, my spiritual leadership invests a great deal of energy and creativity into Tisha b’Av.

Tisha b’Av in Past Years

In past years, I trashed my synagogue on Tisha b’Av. Because each Jewish house of worship is a successor to the First Temple and Second Temple whose destruction tradition associates with Tisha b’Av, I rendered the Tisha b’Av feel physically in my community’s sacred space.

Each year with a different theme (e.g. antisemitism as such, immigration and border issues, environmental, etc.), I curated an experience of loss that participants could feel viscerally, then a gentle uplift to recalibrate and set a tone for the seven weeks ahead. Each Tisha b’Av has been a descent for the sake of ascent (in Hebrew, yeridah tzorekh aliyah) – first destruction, then the first glimmer of hope, a first High Holy Day tune, a repair of the space, rising higher and higher.

A few communities have tried this idea, which might feel familiar to alumni of Jewish camping experiences for children and teens. Others have reported wanting to try it but facing opposition from community leaders afraid of excess shock, hurt, feel or meaning if their sacred space were treated as anything else.

We Need a Different Approach This Year

I can’t bring myself to wreck my shul this year. I just can’t do it. I don’t think it would be wise this year, and this year’s spiritual calendar itself offers another way forward that, in my view, better aligns with where people are (and need to be).

Nobody reading this post needs a reminder that we’ve begun the third year of the still ongoing covid-19 pandemic, amidst more simultaneous national and planetary crises than we’ve seen in our lifetimes. Millions have died from covid-19. Democracy itself is in peril as perhaps never before in the U.S., with ripple effects worldwide. Climate change is an accelerating global crisis. The war in Ukraine upends the world order, food security and energy security. Naked and open antisemitism is resurging. Gun violence is turning schools and communities into killing fields. Race, gender, sexual orientation – the list goes on and on, a seemingly daily tumult for years.

Just writing this list, I myself needed to stop and breathe. Already lots of people are numb, avoidant, anxious, fragile and/or angry – with good reason. It’s been too much or too long. Then again, we can’t hide forever from reality and stay real.

So on balance, to me it seems unwise this year to curate an intentional Tisha b’Av experience of collective breaking. Would people come? Could people be skillfully lifted afterward? I think not.

What most people need now is comfort and meaning. In some ways, emotionally and psychologically many experience themselves as living Tisha b’Av most every day now. (No, the acute collective destruction of Tisha b’Av isn’t an everyday experience for everyone. Then again, are we more like the experimental frog being slowly boiled so we don’t jump away?) And yet, the Tisha b’Av purpose of making space to experience collective breaking and loss is still vital, as is the seven-week launch to Rosh Hashanah, the descent for the sake of ascent.

A Tisha b’Av for Shmittah and Shabbat

This year’s spiritual calendar offers two features that helpfully invite a different take on Tisha b’Av.

The first is this shmittah year, the seventh year of the cycle in which we take stock, lay fallow and invest in the future. A shmittah year’s focus is existentially optimistic: it’s a letting-be with a felt sense of enoughness, a time to recover and begin musing for the future without yet efforting the future into being. This feel of the shmittah year is utterly incompatible with the Tisha b’Av core of utter devastation and raw suffering, in which one allows oneself to feel that there is no future. From the Jewish axioms that the rare supersedes the common, joy supersedes grief and Torah supersedes rabbinic decree, the rare shmittah born in Torah must relieve the darkest depth of Tisha b’Av that came later.

The second spiritual twist is that this year, Tisha b’Av falls on Shabbat. Because we don’t fast or ritually mourn on Shabbat, tradition shifts Tisha b’Av forward one day: thus, this year, Tisha b’Av (“the Ninth of Av”) will be commemorated on the Tenth of Av. But the same tradition offers that on the afternoon of Tisha b’Av, hope (some say moshiah / messianic consciousness) is reborn and the updraft begins. If so, then this year’s “Tenth of Av” Tisha b’Av, for the sake of Shabbat, already is lifted “off the bottom,” so to speak. Shabbat eclipses Tisha b’Av, and with it the light already is starting to return.

A Tisha b’Av for the shmittah year, and also honoring Shabbat, therefore must be different if it’s to be authentic to the spiritual flow of days and years. There can be space to experience grief and loss, but modulated – not so low, because we’re off the bottom. There can be hurt, but also hope – not total devastation, because we’re off the bottom, and because the shmittah year is fundamentally optimistic.

Thus I come to a Tisha b’Av of hope – a contradiction in terms, perhaps, but one that fits this season. It’s why I gravitated to Amanda Gorman’s “Hymn for the Broken,” for its hope-fueled resilience that was honest about the hurts but not encased in them. It’s why this year’s Tisha b’Av will make space for descent – some Lamentations – and make more space for ascent, the doggedly Jewish resilience tool of forging hope out of hopelessness. It’s why there can be a memorial candle but not a deliberate destroying of sacred space: the shmittah is to let be and let space be so that it can refresh for the future.

There will be a future. It’s on us to make it so. A Tisha b’Av dedicated to that might be exactly what our communities need now.

A Postscript by R. Alan Lew z”l

Life bets that we won’t be willing to endure the suffering it requires. Life bets that we will try to shut out the suffering, and so shut out life in the bargain. Tisha b’Av sidles up to us, whispering conspiratorially with a racing form over its mouth. Tisha b’Av has a hot tip for us: Take the suffering. Take the loss. Turn toward it. Embrace it. Let the walls come down.

And Tisha b’Av has a few questions for us as well. Where are we? What transition point are we standing at? What is causing sharp feeling in us, disturbing us, knocking us a little off balance? Where is our suffering? What is making us feel bad? What is making us feel at all? How long will we keep the walls up? How long will we furiously defend against what we know deep down to be the truth of our lives?

Will we turn? Will we let the walls of our psyche fall with the walls of the Great Temple? Will we let in the truth we have been walling out all year long and let this truth help us to stop making the same mistakes again and again? Will we let this momentum of consciousness help us break the unconscious momentum of our lives? Will we move from a state of siege to a state of openness, to a state of truthfulness, especially with ourselves?

What might we see as a result? What deep wellspring would suddenly become apparent to us? What pattern would we see ourselves repeating? What larger gesture would we see about to complete itself in our lives? What do we need to embrace?

The walls of our soul begin to crumble and the first glimmerings of transformation – of teshuvah – begin to seep in. We turn and stop looking beyond ourselves. We stop defending ourselves. We stop blaming bad luck and circumstances and other people for our difficulties. We turn in and let the walls fall.

Our suffering, the unresolved element of our lives, is also from God. It is the instrument by which we are carried back to God, not something to be defended against but rather to be embraced. And this embrace begins here on Tisha b’Av, seven weeks before Rosh Hashanah, so that by the Ten Days of Teshuvah, we are ready for transformation. We can enter the present moment of our lives and consciously alter that moment. We can end our exile.

We can step outside our walls and feel the full force of the great tidal pulls on our body and our soul; sun and moon, inhale and exhale, life and death, the walls building up and the walls crumbling down again.

— R. Alan Lew z”l, This is Real and You Are Completely Unprepared, pp. 62-63

Poem by Amanda Gorman; set to trope by Rabbi David Evan Markus, a founding builder at Bayit.