Mad at Alan Lew

I’m mad at Alan Lew.

I’m mad at Alan Lew.

I know he died in 2009, and I hope his memory blesses us all, but I’m mad anyway.

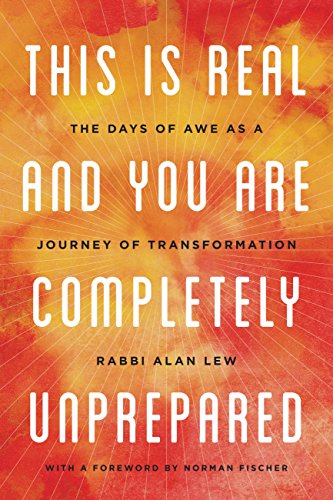

Rabbi Alan Lew is author of the now-classic book This is Real and You Are Completely Unprepared, published in 2003. The subtitle explains the purpose: The Days of Awe as a journey of transformation. It is a road map, week by week, from Tisha B’Av, the lowest point in the Jewish year, through the High Holidays, arriving at our collective sukkah of joy. It is a masterful book. I avoided reading it for many years. People loved it too much. It seemed too powerful. Who needed to feel all those extra feelings? What if the book made me change the way I practice and the way I approach the holidays? I have enough to feel!

But last year, my rabbi ran a weekly summer book club and I had to read it at last. My paperback copy, with the more recent orange cover, is filled with underlines and callouts and connections. I could see why this book is so well-loved. I was mostly loving it, too.

Until I hit what he wrote about Torah portion Ki Tetze.

In Chapter Four, Lew discusses the parshiot (Torah portions) we read during the month of Elul and lays out spiritual practices to make the month more meaningful. On page 85, he begins discussing parashat Ki Tetze and my margin notes get very loud. Returning to this a year on, I am calmer, but still feel he missed the mark here, badly.

Lew is trying to tie the instructions in the parasha to our self-awareness. But the instructions are on taking women captive as “wives” after victory in battle. First off, Lew doesn’t seem aware that he’s writing from a heterosexual, male point of view, which is the same point of view as the parasha (but over 3000 years later). By only looking with this male gaze, he immediately loses more than half the humans on the planet. No women speak here.

The women who are captured are taken home, as their loved ones lie unburied, and left to mourn for 30 days. Lew treats this thirty-day delay as a tempering of male desire, where a woman’s first thought on reading it might be that he is waiting to see if she is expecting a baby; a baby fathered by someone recently slain. After 30 days he may become her husband–a euphemism for entering into a non-consensual sexual relationship. Will she be the third wife? Will her children with him be integrated into the tribe, or always be outsiders?

Then, Lew conflates post-battlefield rape, which he posits as “desire,” with romantic relations between men and women. He says on page 87, “…carefully done fingernails, well-coiffed hair, and alluring dresses are still frequently employed to arouse a passion in a man sufficient to get him under the wedding canopy.” So modern marriage is characterized as a woman tricking a man into marriage by driving him wild with desire. Do men not benefit from marriage? Medical evidence shows it’s the best thing for their health. Do men not often choose to show their best side during courtship and then let it all hang out afterwards? Must we stay locked in this binary, and not acknowledge gender as a spectrum, and marriage as between any two humans? I object to the whole characterization of women luring men under the chuppah.

Women reading Parashat Ki Tetze must perform a mental calculus. Is it better to fix oneself up, and flirt, and be taken captive to a strange land, to integrate with this conqueror’s household, or better to be raped and killed right here in my town? Not really the thought experiment any of us wishes to undertake, but we all have tales to tell from modern life, from our friends’ lives or our own, that make this feel all too real.

And Alan Lew missed the whole thing.

I know that the book is 90% great (maybe 95%; let’s not quibble) but I feel that the errors in this section are egregious enough that I cannot let them go unchallenged. I wish more than anything that Rabbi Lew were here with us, so I could give him a good proper argument to his face. It feels unsettling to contradict someone so well-loved who only recently died–very different than disagreeing with a voice in Talmud (circa 500 CE), or with Maimonides (d. 1204 CE) , or even with people who died who I loved. (Yes, I still fight with my favorite Hebrew school teacher, Mrs. Scheinbaum, and my dad and grandma, all of blessed memory. Not all at the same time though!)

I know I must not be the first one to react strongly to this section of Lew’s book and perhaps others have written about it before. If you are reading something, and it is hurting you, know that you can keep the parts you love, struggle with the parts that are difficult, and outright reject the parts that are harming you. After all, we struggle with the Torah itself when we read these difficult topics; we should be trying to give voice to those who were not offered a chance to speak, like the captured foreign women, not skipping past and sweeping it under the rug. Should we take a razor blade and cut out pages 85-92? I don’t think so. But I hope as you read those pages, this year and in the years to come, you stop to think about who is speaking to (or for) whom, and how we can strive to repair old hurts. Truly this is in the spirit of teshuvah we learn in the book.

If you are writing a book, you should have someone else read it who is not like you. It’s a shame that none of Rabbi Lew’s early-draft readers noticed these blunders, which can cause a lot of pain – surely the opposite of his intentions, especially at this season. This book is a great spiritual tool, and it also has a glaring blind spot. Can we use that truth to inspire us to look at our own blind spots?

Shanah tovah to you all, and may you be blessed with a sweet, happy and healthy year.

Shari Salzhauer Berkowitz, creator with Steve Silbert of the contemplative spiritual-creative volume Color the Omer and a regular contributor to Builders Blog, is a professor of Communication Disorders and a speech-language pathologist. She serves as a lay service leader and Vice President of Temple Beth El of City Island, NY, also known as “your shul by the sea.”